Denise Y. Ho, Yale University

Summary

Big-Character-Posters served as forms of propaganda throughout the Mao era, and were especially prominent during the Cultural Revolution. This biography examines the history and legacy of the big-character-poster, especially the ways they were used by individuals to spread ideology and serve as a form of mass mobilisation. From Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution to students during the Umbrella Movement, big-character-posters are often seen as a bottom-up form of protest. However, oral histories and memoirs reveal that the process of writing them was more complicated, sometimes top-down and sometimes collectively authored.Introduction and Origins

A big-character-poster may be defined as a type of political writing, expressed on paper—in handwritten characters—and posted in a public place; a wall covered with such posters established a forum for discussion and dissemination. Big-character-posters played a role in the Hundred Flowers Movement in 1956, during which individuals were encouraged to express their opinions on contemporary politics. In 1958, Mao Zedong wrote that ‘a big-character-poster is an extremely useful new weapon. It can be used anywhere as long as the masses are there…It has been widely-used, and should be used indefinitely.’1 Big-character-posters thus became instruments for mass mobilisation, especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). During that tumultuous period, they were used to expose enemies of the revolution, accuse them of crimes, and call for class struggle against them.

Though the Big-Character-Poster is most often associated with the period of the Cultural Revolution, it had precedents in earlier periods. Writing on the cultivation of national identity in the Republican era, historian Henrietta Harrison shows how ordinary people celebrated National Day by writing scrolls with republican sentiments. After the death of Sun Yat-sen, China’s founding father, the walls of Central Park in Beijing were covered with funerary couplets, contributed not only by civic associations and Party branches, but also by private individuals. Beyond declarations of loyalty, posters could also be used for dissent: historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom’s analysis of student protest repertoire includes the use of banners and posters challenging Nationalist policies. In these ways, big-character-posters were part of the birth of Chinese nationalism.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the new regime took strict hold over political discourse, both through control of media and publication and through the creation of new political language. In contrast to official media, which is controlled by the state, the big-character-poster is seen as a bottom-up mode of expression, and as a way of making revolution at the grassroots. However, there is evidence that people were taught how to write denunciations in the Socialist Education Movement, and certainly Mao and other leaders encouraged their use.

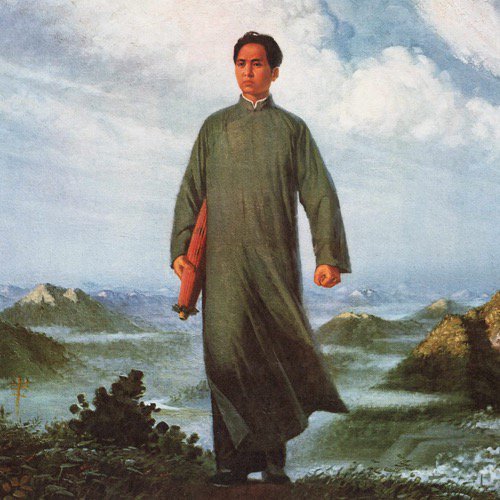

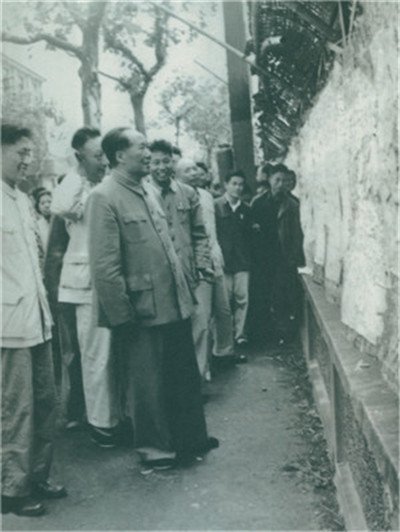

For example, Mao was known to publicly view others’ big-character posters, as he is here during the Anti-Rightist Campaign.2

This campaign followed a previous Hundred Flowers movement, during which individuals were encouraged to speak openly about problems in society. Many did so, penning criticisms of the party system and cadre privilege. Taken together, these expressions of dissent revealed the contradictions and fissures in ‘new society,’ as China after 1949 was called. But the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which attacked those who had spoken out, silenced many of these critical voices. In an era of political change, the bottom-up employment of the big-character-poster was a great risk for its author.

Big-Character-Posters During the Cultural Revolution

It was during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) that big-character-posters gained the status of an icon. Mao himself wrote a big-character-poster calling on others to ‘Bombard the Headquarters,’ or an attack on the Party; thus the genre of the poster served as a form of authorization. [See ⧉source: Bombard the Headquarters poster, also depicted to the right ⧉source: Translation of 'Bombard the Headquarters' poster]

Indeed, the Central Committee’s decision on the Cultural Revolution supported their use ‘to argue matters out.’ But the line between verbal struggle and physical struggle was tenuous. While on the surface the big-character-poster represented using words for class struggle, the language of Cultural Revolution posters dehumanize the accused, employ martial language, and call for violence. In examples written during the summer of 1966, posters accused people of being ‘anti-Party,’ ‘anti-socialist,’ and ‘counter-revolutionary,’ calling upon readers to sweep away ‘monsters and demons’ and repay a blood debt with blood.

As oral histories attest, for many the big-character-poster was symbolic of ‘making revolution’ during these years. One interviewee, a middle school student in the suburbs of Shanghai in 1966, recalls that in the beginning she didn't know how to write them, but through traveling to Beijing and copying posters at Peking University and Tsinghua University, she and her friends ‘thought that this seemed to be part of the revolution.’ [See ⧉source: Interview 'Copying big-character posters as part of the revolution'] For others, as another testimony reveals, an individual decision to speak out made the writing of a poster a weighty decision. One informant, a factory worker, put up a poster in Shanghai's People's Square, asking ‘Does truth have a class element?’ [See ⧉source: Interview resistance during the Cultural Revolution] In this 1972 case, the worker wrote the big-character-poster as a form of political self-expression, carefully calculating the risk to his family, sneaking out to paste it short before dawn, and spending three nights in jail after confessing to the act.

Cultural Revolution big-character-posters were powerful political texts. However, recent memoirs reveal that the process of writing them was not always so straightforward. In a book of essays entitled China in Ten Words, the writer Yu Hua recalls how authoring big-character-posters was a way to make sense of his place in the world. From his childhood dread at anticipating his father's name in big-character-posters, Yu Hua is directed by his father to write his first poster in order to accord with what he describes as both self-criticism and his father's ‘exhibition of political theater.’ Writing the poster becomes a family affair, including his mother and his brother. His parents explain, ‘We ourselves were the objects of criticism in this poster...so it should be placed on view in our own house, alerting us constantly to our past errors and ensuring that in the future we would always stick closely to Chairman Mao and travel far on the correct path.’3 This anecdote reveals the extent to which big-character-posters were performative, here acting to protect Yu Hua and his family by demonstrating that they had already begun to reform themselves.

In the tumult of the Cultural Revolution, the big-character-poster also served as a form of information. Posters were read and copied. Some of the most famous big-character-posters were broadcast via the Central People’s Radio Station. Posters with local targets could be read over the loudspeaker in individual work units or on college campuses. As the world outside of China struggled to make sense of its ‘continuous revolution,’ it utilized the big-character-posters that circulated beyond its borders. Japanese correspondents translated posters into English to be shared with others in international media; telegrams to the American consulate in Hong Kong from the Office of the British Charge d’Affaires in Beijing summarized posters and sometimes quoted them in full, referring to one week’s ‘poster take’ or labeling memos ‘Peking Posters.’ The circulation of such posters affirms their role as a source of news.

Big-character-posters even spread beyond China’s borders. Trains that originated in China and arrived in Hong Kong were, during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, sometimes plastered with posters denouncing British imperialism. In addition to appearing at China’s border with Hong Kong, they spread throughout the British colony, including at leftist schools, Chinese department stores, and Chinese companies. The big-character-poster was weaponized on sites that symbolized British control, such as Government House in the city’s Central District. At the height of political tensions in 1967, the Hong Kong government banned posters, a move that the leftist press—represented by Ta Kung Pao, among others—condemned, rallying readers instead to engage in a 'poster war.'4 [See ⧉source: Hong Kong Ta Kung Pao Article]

Big-Character-Posters as a Persistent Political Repertoire

The use of big-character-posters did not end with the Cultural Revolution. Posters appeared in 1976, and were central to the Democracy Wall movement in 1978. The most famous poster of this period was Wei Jingsheng’s call for democracy as a ‘fifth modernization.’ [See ⧉source: Wei Jingsheng's 'fifth modernization'] The state responded by eliminating the clause in the Constitution that allowed people the right to write big-character-posters, and the People’s Daily condemned them for their responsibility in the ‘ten years of turmoil’ and as a threat to socialist democracy. Yet big-character-posters reappeared in the Tiananmen student movement in 1989. Though by this time there were many other forms of media available to protestors, such as television, posters were so strongly associated with a tradition of dissent that they retained their persuasive power. During the movement, big-character-posters reflected a broad range of aspirations and demands, from calls for democracy and freedom to lists of specific political reforms. [See ⧉source: The big-character poster in the 1989 Tiananmen protests]

As an object of the Mao era, the big-character-poster retains many of its paradoxes. It is at once a text of the individual and a text of the group. Dissenting voices--some rising to the status of an icon--used it as a medium to reach broad audiences. At the same time, big-character-posters were often written in groups, at the direction of authority, and approved by Mao himself. Thus a big-character-poster could be both a vehicle for protest and a means of control. As a physical object, the big-character-poster was deeply democratic. Paper, ink, and paste were all that were needed, and one could improvise. In the posters on display here, their messages have been written on packing paper, which was the most readily available material at hand.

Their materiality, together with the use of personal calligraphy, makes them authentic and personal, despite the fact that they were made to be ephemeral. In fact, sometimes opposing factions went around tearing down each other's big-character-posters, leading to streets filled with shredded paper. Despite their ephemeral nature, the imprint of big-character-posters on Chinese society remains strong.

Legacies and Afterlives

What are the legacies of the big-character-poster in Chinese society? Very few big-character-posters have been preserved; the exhibition depicted above was an exception and was not without controversy in 2017, over half a century after the Cultural Revolution began. More often, big-character-posters leave their traces as words: records of Cultural Revolution posters written down as contemporary news, collections of Democracy Wall writings gathered by Nationalist authorities in Taiwan, and compilations of 1989 posters preserved for Communist Party cadres to understand the nature of ‘counterrevolution.’ In this way the post-Mao inheritance of the big-character-poster is that of the grassroots voice of conscience. The directed, top-town character of the big-character-poster seems largely to have been forgotten.

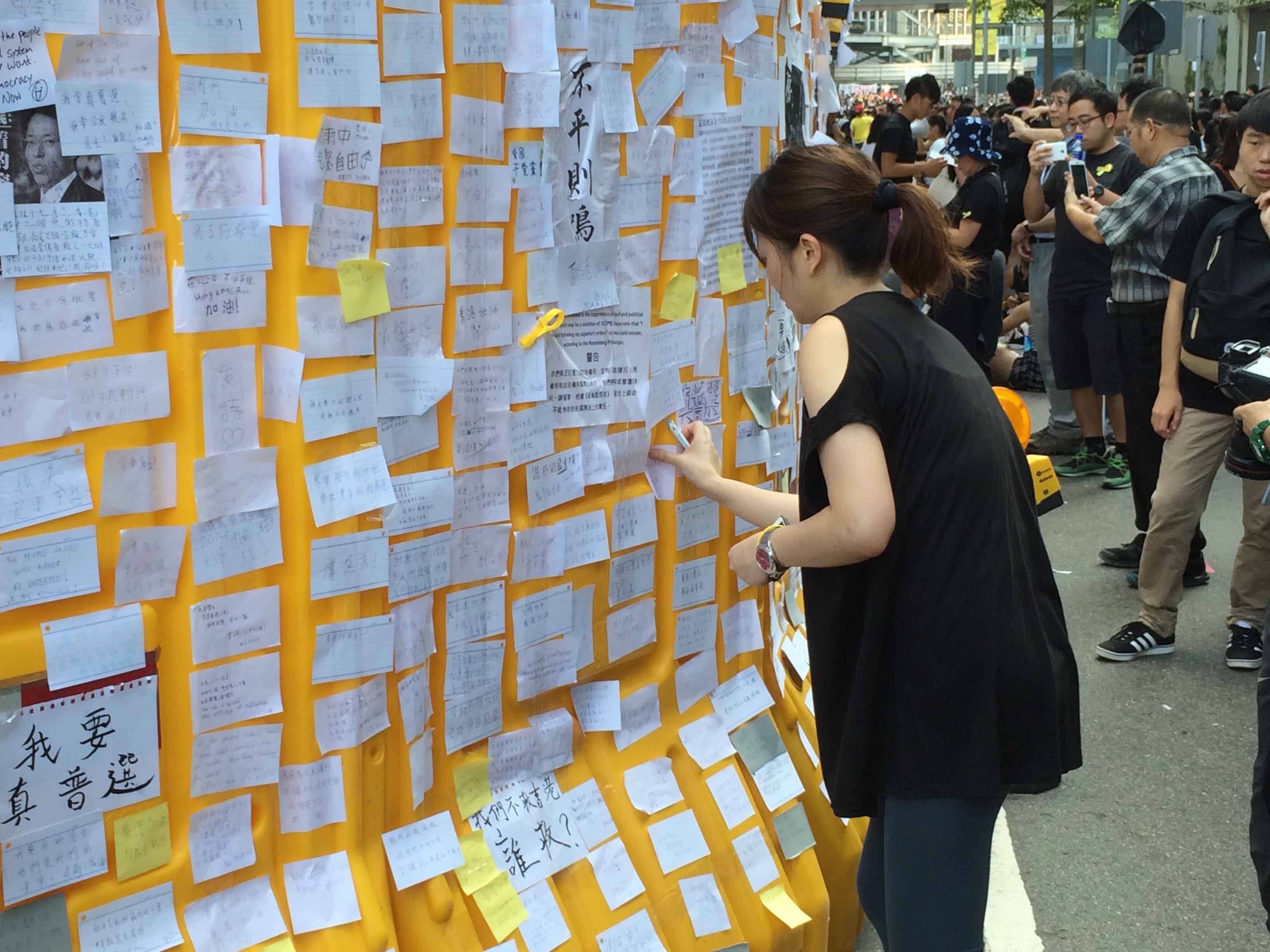

Today, the big-character-poster remains part of protest repertoire. In the 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, individuals appropriated large swathes of urban public space and covered overpasses, sidewalks, and walls with writings calling for greater democracy in China's Special Administrative Region. Many of these ‘posts,’ which then re-circulated in social media, were handwritten on humble post-it notes. In an analysis of over 1,000 such texts, literary scholar Sebastian Veg noted how--taken together--the writings emphasized both broad political claims and specific policies, and drew from classical Chinese tradition and contemporary pop culture. As someone who witnessed the Umbrella Movement firsthand, I observed that these ‘posts’ served multiple functions: they gave individual authors a sense of agency and of being part of a wider chorus, they gave readers a snapshot of what participants at large were thinking and feeling, and--in their preservation--their ephemeral form became permanent words.

Even more recently, in 2018 activists at the storied Peking University used the genre of the big-character-poster to denounce the administration's handling of a request for information on a sexual harassment case, a #MeToo poster for the internet age.5 In this latest iteration the big-character-poster shows itself a flexible medium with persistent power: on everyday paper, inscribed in ink, and in public space.

Footnotes

'Introducing a Commune,' 15 April 1958 in Selected Works of Mao Zedong. Available at Marxists.org (https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-8/mswv8_09.htm, last accessed 3 July 2019).

Mao reads big character posters during the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957 Everyday Life in Maoist China, 15 June 2016 (https://everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org/2016/06/15/mao-reads-big-character-posters-during-the-anti-rightist-campaign-in-1957/; last accessed 25 June 2019).

Yu Hua, ‘Writing’, in China in Ten Words (New York: Pantheon Books, 2011), 68.

John M. Carroll, 'A historical perspective: the 1967 riots and the strike-boycott of 1925-26', in May Days in Hong Kong: Riot and Emergency in 1967, edited by Robert Bickers and Ray Yep (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009), 77.

Jia Ao, 'How a Chinese Activist Used Blockchain to Make a #MeToo Letter Undeletable' (Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie) Radio Free Asia 27 April 2018 (https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/blockchain-04272018110005.html, last accessed 25 June 2019).

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Big-character Poster: 'Bombard The Headquarters' Poster

- 文Text Big-character Poster: Translation Of Bombard the Headquarters Poster

- 文Text Big-character Poster: Interview 'Copying Big-character Posters As Part Of The Revolution'

- 文Text Big-character Poster: Interview Resistance During The Cultural Revolution

- ⧉Image Big-character Poster: Hong Kong Ta Kung Pao Article

- 文Text Big-character Poster: Wei Jingsheng's 'Fifth Modernization'

- ▤Pdf Big-character Poster: In The 1989 Tiananmen Protests

Geography

Peking University and Tsinghua University are regarded as China’s top universities, and are located in the suburbs of Beijing. During the Cultural Revolution, students travelled around the country to exchange 'revolutionary experience.' Here, the interviewee in the oral history describes going to these two universities to copy their big-character posters.

The Hong Kong Umbrella Movement unfolded in three major protest areas: Admiralty, Causeway Bay, and Mong Kok.

This is the location in Beijing that gave its name to the movement of 1978. Here on Xidan Street in the Xicheng District of Beijing, individuals put up posters to express opinions about current political affairs. The term 'democracy wall' can also used to describe other sites used in the same way. For example, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the area near the main student center is called 'democracy wall.'

The central place for political gatherings in the city of Shanghai. Here, the interviewee in the oral history describes putting up his own big-character-poster.

Regarded as the center of political power in Beijing, Tiananmen Square is the open space in front of the Forbidden City’s Tiananmen Gate. Around its edges are the Great Hall of the People, the Chairman Mao Mausoleum, and the Museum of the Chinese Revolution (today’s National Museum of China). In the center stands the Monument to the People’s Heroes.

Timeline

Further Reading

On Students and Academic Life

- Lanza, Fabio. Behind the Gate: Inventing Students in Beijing. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N. Student Protests in Twentieth-Century China: The View from Shanghai. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991. See especially Chapter 3, 'Student Tactics.'

- Yeh, Wen-hsin. The Alienated Academy: Culture and Politics in Republican China, 1919-1937. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 1990.

On Political Movements

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. The Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Chinese Intellectuals. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1960. See especially Chapter 8, 'Students.'

- Mittler, Barbara. A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Schell, Orville. 'The Democracy Wall Movement'. In The China Reader: The Reform Era, edited by Orville Schell and David Shambaugh. New York: Vintage Books, 1999: 157-165.

On Visual and Verbal Culture

- Pan Lü. Aestheticizing Public Space: Street Visual Politics in East Asian Cities. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Schoenhals, Michael. Doing Things with Words in Chinese Politics: Five Studies. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, 1992.

- Veg, Sebastian. 'Creating a Textual Public Space: Slogans and Texts from Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement'. Journal of Asian Studies vol. 75, no. 3 (August 2016): 673- 702.

Video

- 'Red & Black Revolution: Dazibao and Woodcuts from 1960s China' Fairbank Center Panel Discussion, 9 November 2017 (https://fairbank.fas.harvard.edu/events/exhibition-opening-and-panel-discussion-black-and-red-revolution-dazibao-and-woodcuts-from-1960s-china/).