Nicolai Volland, Pennsylvania State University

Summary

The citizens of socialist China were avid readers. Books—and translations of foreign novels in particular—were not just a favorite pastime, but also a means of education and cultural work. Translated books told Chinese readers about the world at large, and especially about the Soviet Union, the PRC’s new partner in foreign affairs. This biography zooms in on a popular edition of a translated Soviet novel, searching for the traces of Sino-Soviet relations, from the PRC’s founding to the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. It aims to excavate the history of reading (foreign) books in socialist China.A Visit to the Library

On or around 26 October 1960, Song Huanwu 宋焕武 borrowed a slim book from the library of the Hubei Worker & Peasants Fast-Track Middle School (WPFM). We know very little about Song. He was most likely a student at the WPFM. His was not a regular middle school. Rather than the full three-year curriculum of secondary schools common in the 1950s and early 1960s, WPFM offered an abbreviated path to a middle school diploma for adult learners. As its name suggests, WPFM helped students with very limited previous schooling—often arriving with just a few years of primary education—to gain the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in their workplace. Many schools of WPFM’s kind operated on a part-time schedule, allowing their students to remain attached to their work units (danwei 单位) and keep working while expanding their education. Song probably was such a student: Coming from a peasant or, more likely, worker background, but eager to make use of the opportunities the socialist state offered to people like him. His determination to enhance his skills bespeaks the ambitions of a man from humble origins.

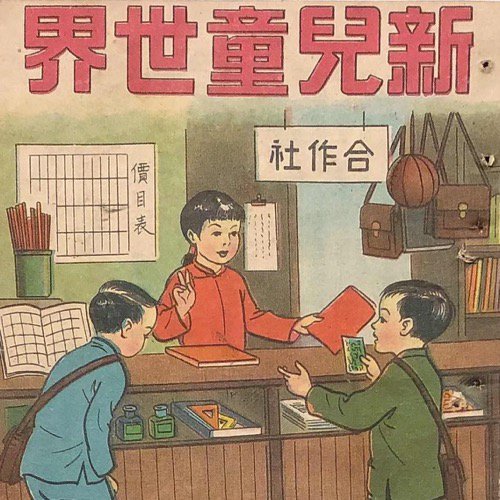

Apart from formal classes, the easiest way for students to enhance their education was reading. Students read newspapers, bulletin boards mounted on walls, and books of all kinds. Yet books were an expensive commodity. To provide students from humble backgrounds—such as Song Huanwu—access to books, schools and work units across China set up libraries and reading rooms in the 1950s. This essay takes a close look at the commodities housed in these libraries: Books, and especially Chinese translations of foreign books. Socialist China was outward looking, and the widespread curiosity about the world beyond its borders was reflected in a tidal wave of translations. As we will see, students like Song Huanwu were especially drawn to the shelves housing these translations.

Traces of a Reading History

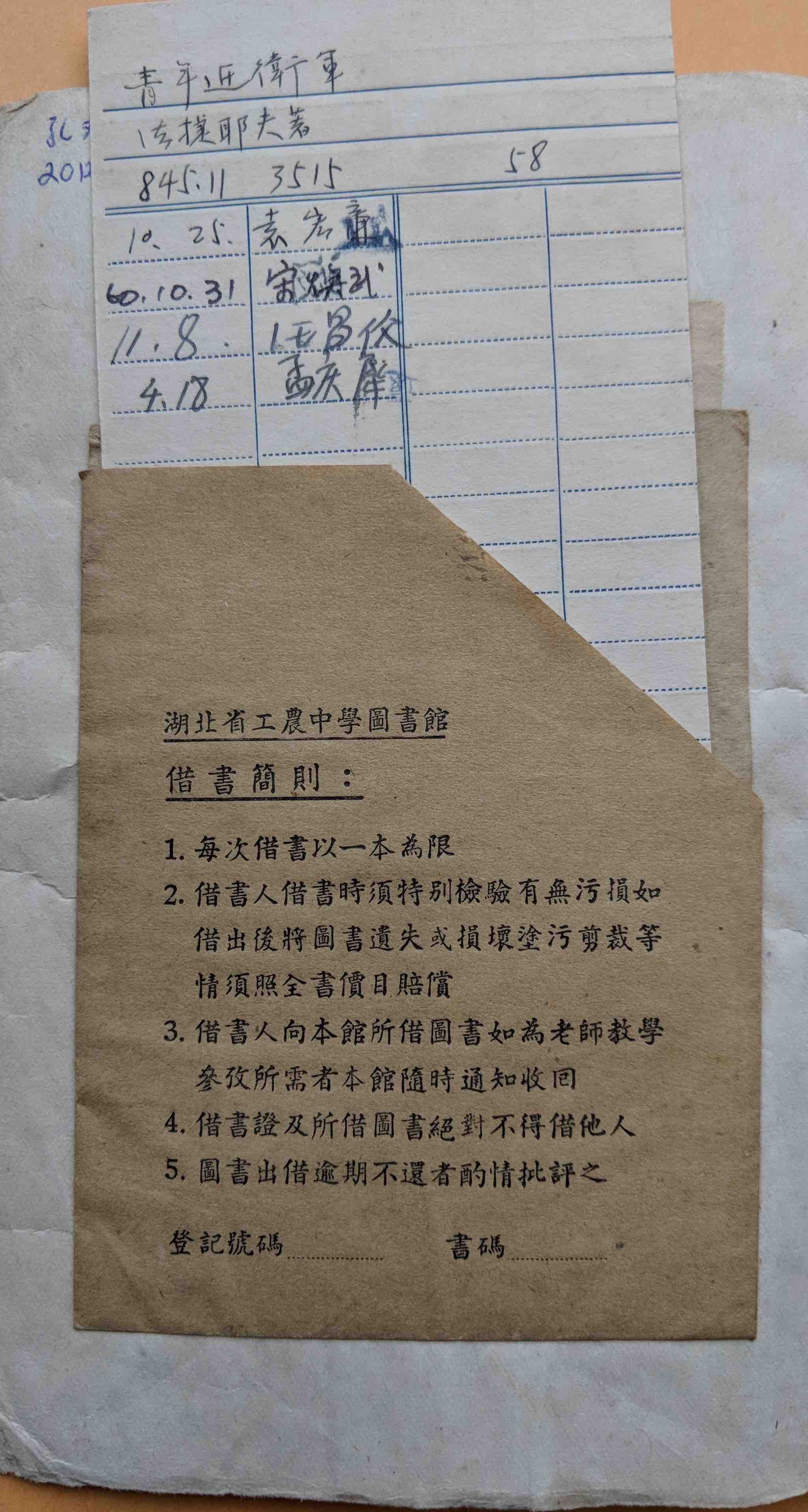

Song seems to have been an avid reader. We know of Song only from a small circulation card, slipped into a paper pocket glued to the inside of the book’s back cover [see ⧉source: Circulation card 1, also depicted to the left]. The card lists the names of borrowers and the due dates when the book had to be returned to the library. A second card, pasted on the facing page [see ⧉source: Circulation card 2], would list the same information, this time for the reader, to remember when they had to return their books. Cards like these, containing information on the circulation of books, were very common in library books in socialist China. Most of them were torn out and discarded when the books themselves were removed from the library shelves, often decades later. But occasionally—such as in this case—the cards have survived, giving us bits and pieces of information that help us to reconstruct the patterns of reading in the 1950s. The same library card that tells us Song’s name also displays the names of the previous and next readers, and the book’s due dates. The reader before Song had to return the book on 25 October. Song was given a due date of 31 October. The next reader’s due date was 8 November. Song thus had barely five days to read the book he had checked out. We need to consider that he had to pursue his studies and possibly also work during daytime, a demanding schedule that left him with little spare time. If indeed he finished the book --and it bears the traces of heavy use throughout, suggesting that many borrowers must have read it cover to cover-- then it is quite remarkable how quickly he read—an avid reader indeed.

Books: Authors, Translators, Editors, Publishers, Readers

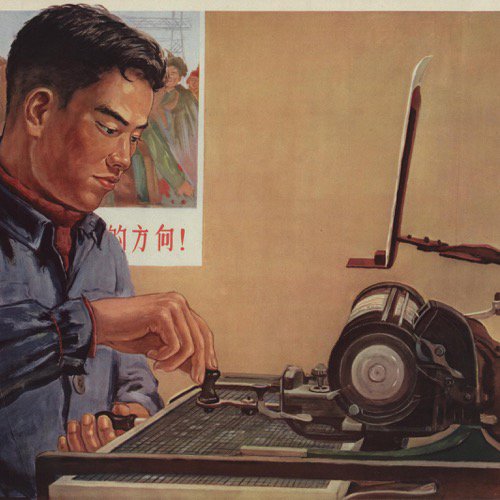

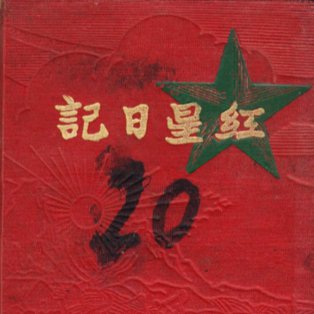

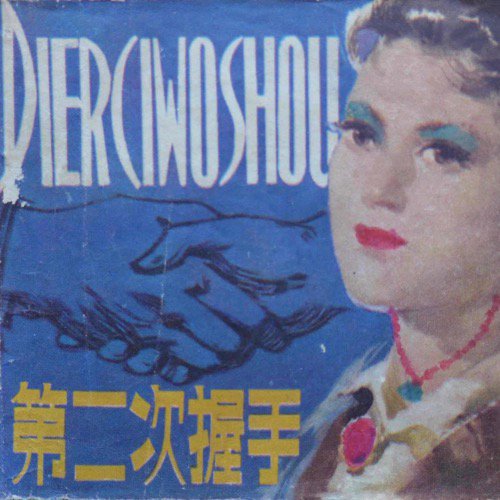

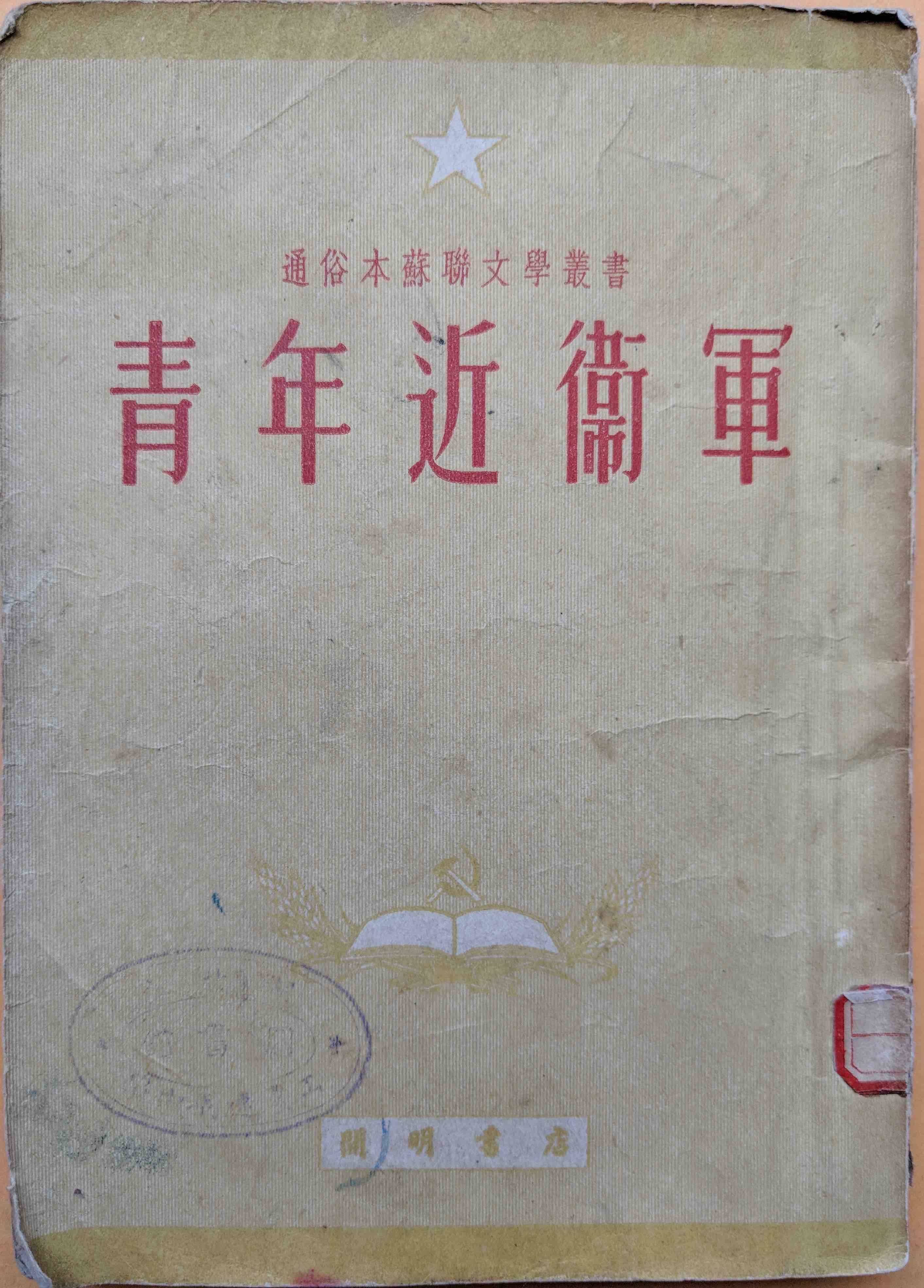

What, then, was the book that had caught Song’s attention on the library shelves? A pocket-sized volume with the title The Young Guard (Qingnian jinwei jun 青年近卫军) [see ⧉source: The Young Guard, also depicted to the right], emblazoned in large red characters across the cover. The Young Guard was in fact not a Chinese novel. The book’s author, Alexander Fadeev (1901-1956), was among the most prominent Soviet authors of his day. Fadeev was seventeen when he joined the Bolshevik party and fought on the side of the fledgling Communist regime against the White Army in the bloody civil war that consumed the first five years after the October Revolution in 1917. Exchanging his gun for the pen, Fadeev wrote a novel depicting his wartime exploits, The Rout, which was published in 1927 and became an instant bestseller. Fadeev’s most popular book, however, was to be The Young Guard. Appearing in 1946, the novel tells of the operations of an anti-Nazi resistance organization during World War II. With its captivating prose and remarkable lack of political doctrine (Fadeev would be forced to rewrite the novel in 1951, to bring it in line with the ideological requirements of the day), The Young Guard was a staggering success. It was awarded the all-important Stalin prize and became the second most popular work of literature for children and young adults in the entire 74 year-history of the Soviet Union, selling over 25 million copies. An overlength film version of the novel, directed by star director Sergei Gerasimov, was released in November 1948, reportedly selling 48 million tickets. By 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded, Alexander Fadeev was at the height of his career, having been made chairman of the Union of Soviet Writers.

Once the young PRC embarked on its drive to 'learn from the Soviet Union' in 1949, Fadeev became a household name in China as well. In October that year, Fadeev led the first delegation of Soviet writers, artists, and scientists to the People’s Republic on a whirlwind tour of Beijing, Shanghai, and other cities that included multiple public speaking engagements and meetings with Chinese writers, as well as the PRC’s political leadership [see ⧉source: Fadeev in Shanghai]. A Chinese translation of The Young Guard had appeared in December 1947, from the hand of the accomplished translator Ye Shuifu 叶水夫 (1920-2002), and published by the Epoch Press (Shidai chubanshe 时代出版社), a Sino-Soviet joint venture that specialized in translations of influential Soviet literature. By the time Fadeev visited China in October 1949, the Chinese translation was in its third printing and had sold 6,000 copies. In the climate of close cooperation between the PRC and the Soviet Union in the early and mid-1950s, Chinese publishers produced a torrent of translations of Soviet books of all stripes, from technical manuals to social science textbooks to novels for both adult and young readers. The Epoch Press alone, which published the first Chinese edition of The Young Guard, produced almost 800 such titles between 1949 and 1956. Soviet reading matter was ubiquitous in bookstores and on library shelves, and was recommended by school teachers. It was little wonder that Song Huanwu was drawn to the title he discovered in his school’s library.

Popular Reading Matter

The book Song took home from the WPFM library, however, was not Ye Shuifu’s translation. Fadeev’s novel, while written for young readers, is a complex work of fiction of close to 500 pages—more than students at an institution such as WPFM would be able to deal with. Students from worker and peasant backgrounds tried to improve their literacy skills, but a lengthy novel would likely exceed their skills, time, and patience. Chinese publishers had early on recognized this problem, and set out to produce abbreviated editions in order to make major works of literature available to broader audiences. The volume Song Huanwu found in his library contained 148 pages—a third of Fadeev’s original—and was published by Kaiming Bookstore (Kaiming shudian 开明书店), in its Popular Editions of Soviet Literature series (Tongsuben Sulian wenxue congshu 通俗本苏联文学丛书). The Popular Editions Series, the publisher explained, aimed to help readers who 'either are not used to reading translations,' or do not have the time to read lengthy originals, with simplified grammar and a stripped down plot [see ⧉source: Advertisement in The Young Guard].

It is not too surprising that Kaiming Bookstore decided to launch a series such as Popular Editions. Kaiming (literally, 'Enlightenment') had been founded in the 1920s and had made its name—and its fortune—with a series of popular textbooks. Reading materials for young readers had always been at the heart of Kaiming’s mission. It was only apt that, when it refocused its business in the early 1950s, Kaiming looked to the Soviet Union as an inspiration for new sources of public enlightenment. Other titles in the Popular Editions Series include Feodor Gladkov’s Cement, Mikhail Sholokov’s Virgin Soil Upturned, Valentin Kataev’s Time, Forward! and Boris Polevoy’s Story of a Real Man—all classics of socialist realism, the officially endorsed literary style in Stalin’s Soviet Union. All books sold for relatively modest prices; The Young Guard retailed for 5,400 Yuan [see ⧉source: Kaiming Bookstore logo and price], about twice what an issue of a literary journal would cost, but significantly less than other, more lavishly produced books. Paperbacks printed on cheap, locally produced paper, all books in the series sported a uniform cover [see ⧉source: Book covers of Popular Editions Series, also depicted to the left] and came with a two page summary of the plot and a cast of characters, to assist readers [see ⧉source: Summary of The Young Guard].

Kaiming issued the first set of nine titles in the Popular Editions Series in January 1951; by April, many of the books were in their second edition, bringing print runs to 10,000 copies each. Three more volumes appeared in December, and in August 1952 the publishers supplied an abbreviated edition of the single most popular Soviet novel in China, Nikolai Ostrovsky’s How the Steel was Tempered. A must-read for generations of Chinese growing up after 1949, Steel was popular enough to warrant an initial print run of 40,000 copies. Overall, the series seems to have been a success. Kaiming might even have considered issuing further volumes; in 1953, however, the privately held company was merged with the state-owned Youth Press (Qingnian chubanshe 青年出版社) into what became Chinese Youth Press (Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe 中国青年出版社), the main publishing house catering to young readers to the present day.

Kaiming, however, was not the only publisher to issue abbreviated versions of popular novels. In fact, such re-writings (gaixie ben 改写本) constituted a lively genre in the 1950s. Just months before Kaiming’s version of The Young Guard, another publisher, the Everluck Press (Yongxiang yinshuguan 永祥印书馆) had published a 99-page version of the same book. And in 1953, the East China People’s Press issued an even shorter version of The Young Guard, for use as 'supplementary reading material in fast-track literacy classes' that taught basic reading skills to adults—an audience with even lower reading skills than the classmates of Song Huanwu. The reading landscape of the 1950s, thus, was composed not just of an ever expanding number of both translations of Soviet literature and new Chinese writings, but also of multiple, and sometimes competing, versions of these books. There were many different avenues through which readers could access the canonical novels of the day—from Russian originals for those who had mastered the language, to the full translation by Ye Shuifu, to multiple abridged versions, and finally to film and theater adaptions (Chinese publishers issued scripts for two different stage adaptions of The Young Guard, in 1956 and 1959, respectively). The literary field of socialist China was an ecosystem just as complex and diverse as the reading public itself.

Reading and Politics

By the time Song Huanwu got to read The Young Guard, however, the PRC was undergoing momentous changes. In October 1960, when Song borrowed the book from the library, the nation was reeling from the disastrous results of the Great Leap Forward. The school Song attended may actually have been a product of the Leap: In the frenzy to leap ahead into the ranks of the advanced world, numerous institutions for grassroots education had sprung up, and the Hubei WPFM may have been one of these. On the other hand, as a provincial-level institution located in Wuhan, the metropolitan center of Hubei province, Song’s school also helped to isolate its students from the worst effects of the Leap, including mass starvation in the surrounding countryside. Conditions were dire nonetheless, and Song may have taken up reading Soviet novels of chivalry and adventure in search of diversion from grim reality.

1960 also marked the open break in Sino-Soviet relations. The two nations’ friendship had cooled since the heyday of the early 1950s, but mutual exchanges—political and economic, as well as cultural and literary—did not come to a standstill until after the break. The pace of new literary translations from the Soviet Union now slowed to a trickle, and older editions went out of print. In this light, it may be remarkable that Song turned to Soviet novels when searching for leisure reading—maybe even with a hint of defiance. The thin historical record—really not more than a librarian’s inscription on a circulation card—prevents us from knowing what Song Huanwu thought while reading Fadeev’s novel.

Becoming History

The book itself, the dog-eared copy with its brittle binding, the slim little volume published by Kaiming, seems to have lost its luster and declined in popularity soon after Song returned it to the library. The circulation card lists only two more readers after Song. Some libraries took copies of books that were considered no longer politically appropriate off their shelves. As a matter of fact, we do not even know if Song’s school, the Hubei WPFM, survived the post-Leap reorganization of educational institutions. Practically all libraries closed six years later, at the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, their holdings often dispersed. The traces of the copy Song perused, too, get lost in the upheavals of the following decades. Just as we do not know what became of Song, the avid reader, we lack sources to tell us what happened to the book. The volume itself is silent on much of its subsequent history. Only in 2011, half a century after the dates recorded on the circulation card, it turned up on Confucius Net, China’s leading online platform for sales of used books, where it fetched less than a dollar, purchased by a foreign scholar. It is from this distance that the little book speaks to us today, revealing but the faintest of traces of the lives that intersected with its own existence, in a constantly receding past.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Circulation Card 1

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Circulation Card 2

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: The Young Guard (青年近卫军)

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Fadeev In Shanghai

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Advertisement For The Popular Editions Series

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Summary Of The Young Guard (青年近卫军)

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Kaiming Bookstore Logo And Price

- ⧉Image Borrowed Books: Book Covers Of 'Popular Editions Of Soviet Literature Series'

Further Reading

Bernstein, Thomas P. Hua-yu Li (eds.). China Learns from the Soviet Union, 1949-Present. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010.

Dobrenko, Evgeny. The Making of the State Reader: Social and Aesthetic Contexts of the Reception of Soviet Literature. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Henningsen, Lena. 'Tastes of Revolution, Change and Love: Codes of Consumption in Fiction from New China'. Frontiers of Literary Studies in China vol. 8, no.4 (2014): 575-597.

Link, Perry. The Uses of Literature: Life in the Socialist Chinese Literary System. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Volland, Nicolai. Socialist Cosmopolitanism: The Chinese Literary Universe, 1945-1965. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.