Michael Schoenhals, Lund University

Objects that Mattered (to a foreign student in Mao’s China)

In DDR-Deutsch: Eine entschwundene Sprache (East German: A Vanished Language), Jan Eik elaborates briefly on the noun 'Objekt.' In Socialist East Germany, he notes, it was 'everything that was not a subject; from the construction site to the apartment under operational (operativ) surveillance or the recreation area and state-owned holiday (Ferienobjekt) home where property inspections were occasionally carried out.' In China, then as now, no single noun exists in Chinese onto which all the different shades of meaning of Objekt/object (etymologically rooted in Medieval Latin) may be mapped. My copy of A New English-Chinese Dictionary published in Shanghai in 1975 provides no less than six alternative renderings into Chinese – from the tangible thing or wu (物) to the possibly intangible somethings that our senses perceive, the duixiang (对象) – of what users of the English language may have in mind when they think of objects. In my case, in the excursion below, I have decided to stick with the simple, fuzzy meaning of object synonymous with things or 'stuff' – dongxi (东西) in Chinese. Should I be called upon to do so, I would justify this by making up a story about how one can do more stuff with things than with objects in Chinese...

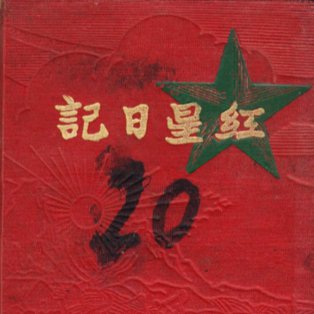

It really all boils down to sources. Mine, this time around, are not something out of a PRC state archive, or even so-called garbage materials from post-Mao flea markets. About the importance of the latter, historian Jeremy Brown has written as follows on his PRC History Source Transparency website: 'Historical material gathered from flea markets and other unconventional places have become the source base for many books and articles about the history of the People’s Republic of China….' In what follows, my ambition is less to write about the history of the PRC than to invite readers to simply think more about the objects that may accompany us in our daily lives and record what happens to them over time. My 'source base' hence really only consists of my own erratic first-hand impressions of things in general scribbled down in a notebook and letters to family and friends during a year of university studies in Mao’s China, from September 1975 to July 1976.

I landed in Beijing on 14 September 1975, as part of a contingent of maybe two dozen European students on that day’s single inbound international flight from the capitalist West, via Karachi. My home for the next month, before moving on to Fudan University (复旦大学) in Shanghai, was to be the Beijing College of Languages (北京语言学院). Just how important certain everyday objects must have been from the outset is something that 44 years later I had completely forgotten but am reminded of when I look at my very first diary entry. It reads in full: ‘Arrived! Beijing yuyan xueyuan, building no. 9, room no. 103. Went to buy stationery in local shop, where they first offered me the cheaper kind! Not like in the West!! Also need to buy lamp, power plug, mosquito net, bowl and chopsticks, detergent, bicycle.’ How, when, and where I had obtained Chinese currency to make these purchases I do not recall, and my diary does not explain it, but presumably we students had all been taken to a bank to exchange our hard currency cash for its Chinese equivalent. If so, it would probably have been the People’s Bank in central Beijing, just off Wangfujing, the only one that handled foreign currencies.

Objects like my enamel rice bowl and chopsticks do not hereafter feature prominently in my diary or letters. What does now and then, however, is my bicycle. Bicycles could not be purchased ‘just like that’ in the area where our university was located. Getting one involved going as a group accompanied by a duly empowered cadre to the Xidan Department Store downtown, where with permission (one bicycle per student) one could pick from among a limited number of Shanghai and Tianjin brands, as I recall it. In his work on Chinese consumerism, Karl Gerth insists that ‘by the end of the Mao era, a young person sought to communicate… [his or her] command over fashion by riding a Forever bicycle.’ This was no doubt so, and my own experience proves that as the new kid in town I had zero ‘command over fashion,’ since for some mysterious reason I chose to purchase a Red Flag made in Tianjin [depicted in the image to the left ]. In retrospect altogether predictably, when I arrived in urbane and sophisticated Shanghai on 27 October, after a long train ride, my diary notes the following: ‘Fudan’s Chinese students make fun of me and my Red Flag bicycle: ’You want one like that in the countryside!’...’ The diary entry that same day contains a further observation on means of transport, about one of the very last Shanghai streetcar lines which at that point had not yet been gutted (it would be, come Christmas): 'The evening tram to Hongkew Park goes 'bling!' as it passes our campus, just like the streetcar off La Playa!' At the time, evidently still fresh in my memory, from having stayed briefly south of Golden Gate Park the year before, was the sound of the green N Judah streetcars in San Francisco.

My deeper impressions of Shanghai in the winter of 1975 were not of consumerism, but of its opposite, if there is such a thing. For most of us foreign Fudan University students (there were a dozen of us, altogether) [depicted in the image to the right], a day spent downtown typically ended by the No. 55 bus stop on The Bund, opposite the Friendship Store. The store – formerly Her Majesty’s Consulate General – was the only place in town where you could get rolls of soft toilet tissue, which all of us (with the possible exception of the British students, who had grown up on Bronco and Izal) tended to prefer over our Chinese roommates' bespoke Liberation Daily (Jiefang Ribao 解放日报) strips. Aside from that, neither we nor anyone else was all that much into conspicuous consumption. There were more important things in life. In a letter to my parents on 9 November 1975, I wrote as follows: 'From the restaurant we walked down to the Bund (the river front) and strolled past the dating couples who were kissing and looking out at the boats in the moonlight (plus the shimmering Mao quotes in neon-lights!). Can you imagine New York high-rises, but not with lights blinking "Buy a Chevrolet!" but reading "Long live Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line!"– Shanghai is an incredible city!’

Back to my bicycle: when time came to leave Shanghai and China in July 1976, I had to dispose of my sturdy Red Flag. One of my tongxue (同学) leaving at the same time was a young Canadian overseas Chinese (her bicycle was one of the fashionable Shanghai brands) with relatives in a Guangzhou suburb. The Fudan authorities informed us that she could let the relatives inherit one bicycle from her, while I had to sell mine back to the state. The authorities were, however, prepared to be flexible and accommodating: when it turned out that the relatives in Guangzhou actually preferred my means of transport to their Canadian relative’s Shanghai urban glider, a student-to-student transfer of ownership papers was permitted. My Red Flag, which for a year had been so looked down upon in Shanghai, would live out the rest of its socialist life in far-away Guangzhou.

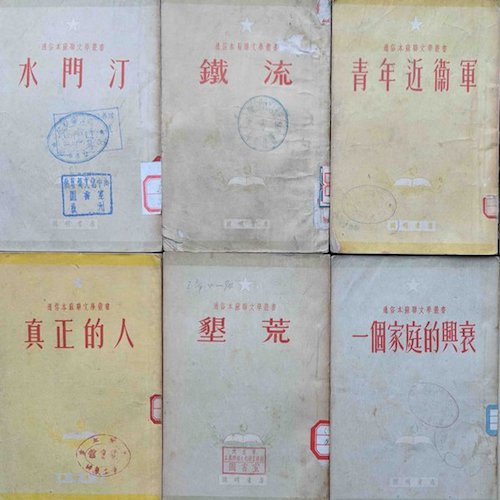

No one thing figures more prominently in my diary and letters in the winter of 1975–1976 than printed matter [see object biographies on ⧉books, ⧉diaries and ⧉magazines]. Mao’s China was full of books and magazines that could not be had back home – home in my case being Stockholm, Sweden. A constant stream of letters often dealt with little else, especially those to a friend of mine who recently had found employment in the Stockholm University Library. Often I wrote about the practical difficulties involved in obtaining specific titles, like in a letter dated 5 November 1975: ‘Now about the Shuihu (水浒): Sadly, I cannot get you the new editions, since they’re only available through the university or through one’s employer, which means I can only get one copy for myself! As for magazines, I’ll soon have most of what I am allowed to buy: a complete run of Xuexi yu pipan (学习与批判) (which, as it happens, is our university journal) and the same goes for Zhaoxia (朝霞), Beijing daxue xuebao (北京大学学报), Beijing shifan daxue xuebao (北京师范大学学报), Jiaoyu shijian (教育实践), Lishi yanjiu (历史研究), plus a few issues of other magazines as well. If you’re interested in more chops, etc. then there’s plenty around, except we’re only really allowed to mail books. There are restrictions on how much one can mail in a year…’

The restrictions imposed concerned not only what one could buy and mail, but also from where one could mail it. This is what I told my parents on a postcard on 3 November 1975: 'The only problem is that the one post office in all of Shanghai from where you send parcels overseas is located way down in the centre of the city.' Why I then went on to say the following, I am today unable to explain: 'But it does not matter much, since I am so busy I really don’t have time to "get" stuff. And one feels less and less like worrying about "stuff" anyway!' I must in any case have asked someone at Fudan about where exactly the post office was located and how to get there, because in my diary the day before, I had jotted down: 'Tram No. 3 to the end of the line, then bus No. 21. Get off at Sichuan Road Bridge across Suzhou Creek. International post office.’

Obtaining new books and magazines was fairly straight-forward: the former were all found in the Xinhua (New China) Bookstores, and the latter in selected post offices. More complicated was finding second-hand books and magazines dating from before 1967, not to mention successfully managing the purchase of items that were truly interesting. In January 1976, I wrote as follows to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) on whose scholarship I was in China: ‘Shanghai has five used bookstores. You can buy old magazines - even those that foreigners are officially not allowed to buy. It seems people don't really know what they can and cannot sell. So please, don't spoil this for the next generation by asking stupid questions. I have attached a short list of university magazines that have been available for purchase so far.’ In the big second-hand bookshop on Fuzhou Road, I was particularly happy when, as I wrote to my parents, ‘I found Lu Xun’s Collected Works (鲁迅三十年集) in 30 volumes, printed in 1947, in excellent condition for 18 yuan (roughly 40 Swedish Kronor), a pittance compared to what it would be back home.’ But sometimes I was less lucky, to say the least. The delicate nature of the transactional situations in which one found oneself at times in Mao’s China is hard to convey, but in my diary in the afternoon of 18 December 1975 (during a week when I was off campus engaged in ‘open door studies,’ so-called kaimen banxue (开门办学), in the Yimin Biscuit Factory, formerly Sullivan’s Bakery) I angrily recorded the following experience in my notebook: ‘During lunch break, went out to buy books. Found the three volume edition of Mao’s Socialist Upsurge in China’s Countryside from 1955 and was just about to pay when a #€%&!-ing cadre stepped up from among the onlookers to tell the shop assistant I wasn’t allowed to buy it (bu hao mai) (不好买). I get so damned furious with these !’#€%&-ers that lecture us for hours about their !%€#-ing ’culture of the masses,’ and then will not even let us buy a book! To #€%& with all this %#€&!!!’

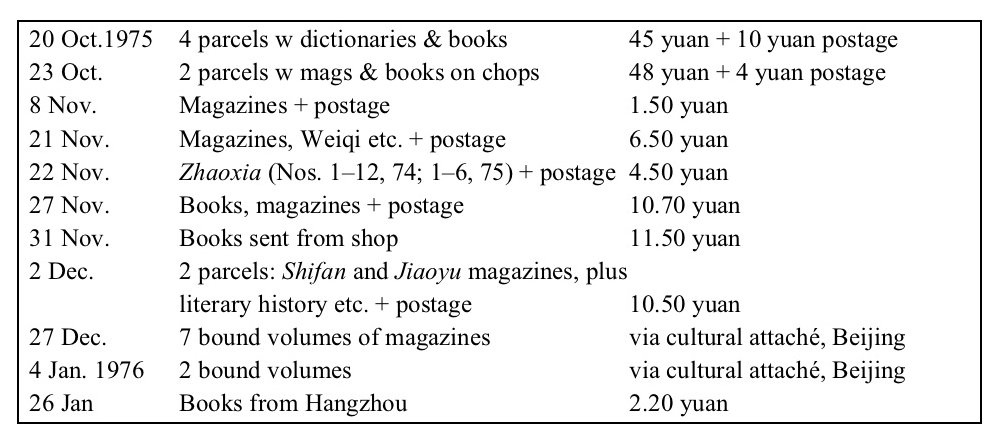

In 1976 I also had some less than pleasant experiences in the Shanghai International post office. As I have explained on the website of the PRC History Group (see October 2014 Document of the Month), there were circumstances under which even books published abroad containing pre-1949 writings by Mao Zedong were liable to be confiscated by post office staff if/when one attempted to mail them out of the country. Most of the time, however, my book parcels proved to be unproblematic. This was a time when 1 yuan still had considerable purchasing power and postage was nothing like what it is today [see ⧉object biography on money]. Entries in my cash book, listing the cost of parcels of books sent to Stockholm from Shanghai, illustrate this:

So much for spiritual food: what about the real food? The most noteworthy thing missing completely in Mao’s China (aside from familiar music) that somehow had to be gotten from 'home' or abroad was, to a student from Western Europe, familiar food items. In Shanghai, the food was generally superb, but it was with the exception of the Cosmopolitan Restaurant on Sichuan Road and the yoghurt in the former French Concession all exclusively Chinese. And, let’s face it, sometimes even the most dedicated Sinophile’s digestive tract yearns for something else. How else do I explain the excitement with which I told my parents in a late December 1975 letter of how ‘I have spent a terrific Christmas in Beijing eating knäckebröd, cheese, liver pâté, Swedish Christmas cooking, and a lot more!’ All of it had been brought in by diplomatic courier, some things from Hong Kong, the rest from Sweden! A few days later, now back in Shanghai, I still refused to drop the topic and went on obsessing about Swedish food in a second letter: ‘Sitting here eating today’s ninth cheese sandwich. I had only just returned from Beijing with a package of knäckebröd in my bag when I found your cheese waiting for me (Note: No customs charge on cheeses!). Tastes wonderful, or like my roommate Liu says, ’There’s something special about food from home!’ Enjoyed a veritable orgy in Swedishness in Beijing, with smorgasbord etc. at the embassy!’ Three months later I wrote home asking for two new Norwegian toothbrushes, because new ‘Chinese toothbrushes look like mine do by the time I want to throw them away. The ones I brought with me have had it!’

Come February 1976, it seems I had discovered and felt a need to elaborate on a curious nexus between my calorie intake and the Red Flag bicycle: ‘My room-mates now and then praise my Chinese and the progress I am making,’ I tell my parents, and go on to say that this happens ‘almost as often as they say that I am getting fatter! This is something I am at a loss to explain, since the scale in Beijing indicated that I had lost a few kilos and my trousers are no tighter than they used to be. I get my exercise by riding around town on a bike that is by now in such poor shape, it grinds to a halt almost immediately once I stop pedalling. Life is full of interesting stuff, but none come for free, that’s for sure!’ In the same letter, dated 6 February, food receives a second mention, but in a different context: ‘I had Hunanese blood pudding yesterday that a peasant brought with him from home, where he had spent the holidays. Yummy!’ Why I am calling this Chinese tongxue a ‘peasant,’ I don’t remember. In late spring I observe how ‘lately the cost of living has gone up from around 0.50 yuan a day to more like 1.50 yuan, but that’s what happens when you want oranges when they’re not in season.’ In November 1975, I had told my parents that ‘Life here comes literally at no cost. We get 120 yuan/month, and that is more than enough to cover food.’

By May 1975, I had become a regular visitor to the Cosmopolitan – the Deda (德大) Restaurant as it was called at the time – just south of the Nanking Road intersection on Sichuan Road. Really getting to know ordinary Chinese was impossible for young foreigners in late Mao-era China, so even something as seemingly ordinary as having a few conversations with an old waiter was a big deal, as I suggest in a letter to my parents: ‘Now and then, I really long to get out of here, when our university cadres are at their worst. But there are bright spots too: I have just gotten to know old Gu (in his early sixties) who works as a waiter in the restaurant Deda, formerly the German ‘Cosmopolitan,’ downtown. He’s a riot and tells all kinds of stories while I order my hamburger and Kartoffelsalat (potato salad). He digs us foreign students, has been a waiter since the age of fourteen, and is a cool dude!’ Elsewhere in my diary I note that Mr Gu spoke of the birth of the PRC not as ‘Liberation’ but as ‘when bossman go home!’

As I look at my letters about everyday life in Mao’s China as a foreign student, the ‘thing’ (pace Lurch) that inexplicably stands out after all these years are the many paired references to eating and cycling (or eating and not being able to cycle as the case may be)! On 9 March 1976 – an apparently ‘rainy and cold day’ – I write ‘My stomach is starting to grow tired of Chinese food and longs for raw carrots and lemon juice. My bike has a flat tire, but who cares when there are almond shaped cracks of light in which one can swim!’ (Note: I no longer understand what that may have been in reference to!) On 18 May, in a letter written after a walk around the fields behind our campus, the food-bicycle nexus is again an object of observation: ‘The mosquitoes are starting to arrive. The birds are already back, as are the frogs. The cucumbers are ripe, and the cauliflower season is over… Classes are no different, but who cares. My bike has a flat tire again, so I’ll have to take the bus to the Cosmopolitan to get my beefsteak and vegetable soup…’

I boarded the Trans Siberian around 8 A.M. on 28 July, to leave China and return to Sweden [depicted in the image to the right]. In Beijing early that morning, there had been a strong earthquake, but as the train left the station I had no idea where the epicentre had been. Four years would pass before I returned to China. At that point, I still gave little thought to the possibility that some of the things I had experienced under Mao would one day become the stuff of everyday history. Not until much later did I learn in the course of many a didactic demi-inebriated post-conference dinner in the company of generous academic elders the extent to which – like scripture and picturing have all along – material objects ‘appear now among people’s multiple everyday practices which demand study.’1 Ergo, welcome to The Mao Era in Objects!

Footnotes

Alf Lüdtke and Sebastian Jobs, 'Introduction', in Unsettling History: Archiving and Narrating in Historiography, edited by Alf Lüdtke and Sebastian Jobs (Frankfurt: Campus, 2010).

Geography

Location of the Peninsula Shanghai off Zhongshan East Road today, this building was formerly used by the Friendship Shop where foreigners could buy daily use items not available elsewhere in Shanghai in the mid-1970s like soft toilet tissues.

Today Shanghai Ancient Bookstore, this is the location of the big second-hand bookshop where Michael Schoenhals purchased a copy of Lu Xun's Collected Works.

The precise location of the little shop was on the north side of Huaihai Road, not far from the Jinjiang Hotel. The shop no longer exists.

This is the location of the campus on Handan Rd in Shanghai, where Michael Schoenhals spent the academic year 1975/6.

This is the location of the Dong'anmen Branch of the Bank of China, where foreigners could exchange currency in 1975/6.