Mary Ginsberg, British Museum

Summary

Political socialization of children begins very young in China. In addition to school classes and textbooks, youth organizations and other group activities, children participate in patriotic learning through officially produced mass media. Children’s magazines were very important in the early years of the People’s Republic, as film, radio and television were not very accessible, especially in rural areas. Magazines promoted communist ideology, specific policies and campaigns, as well as literacy and general knowledge. Publishing in China was nationalized and centralized during the 1950s, ensuring that officially approved messages were disseminated for mass mobilization.Introduction

Children’s magazines were important tools in socialization and propaganda programmes at every educational level. Reinforcing prescribed values, magazines may be effective in ways that textbooks are not. Firstly, in highly mobilized states such as China, with continual social and political campaigns, periodicals carry current messages and changes of policy, unlike textbooks, which are generally only issued every few years. Secondly, Chinese children’s magazines are interactive—full of puzzles and quizzes to solve, models to make or draw, songs to sing and stories to re-tell with the child’s own experiences. A great variety of these magazines appeared during the Maoist period, published for several different grade levels.

Historical background

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, education and children’s literature have played a critical role in nation-building and citizen formation. Socialization in China begins at an early age, since it has long been recognized that children’s political attitudes are influenced even before primary school entry.1 Until the early 20th century, Chinese children’s literature promoted literacy, transmitted general knowledge and instilled traditional cultural values, particularly such Confucian principles as filial piety, loyalty and truth. However, formal education was limited to a very small, elite part of the population. In the early years of the Republic of China (est. 1912), and particularly during the May 4th/New Culture Movements in the 1920s, attitudes toward children’s studies changed dramatically. Curricula included a broader range of subjects (science, world affairs) and children were encouraged to think, rather than memorize. State-sponsored education greatly increased the number of children in school, but even by 1950 the literacy rate was only about 20%. Until the Communist Revolution, children in rural areas (roughly 80%) had extremely limited opportunities for education. From 1949, Maoist reforms centralized education, broadening the system to include more than 28 million primary school children.2 New textbooks emphasized patriotism, a revolutionary collective spirit, and economic production for the new society through practical learning in agriculture and industry.

The longest-running children’s magazine was called Xiao Pengyou (小朋友 Little Friend), produced for first- and second-year primary school students. Launched in 1922 by Li Jinhui (1891-1967)-- better known as the father of Chinese popular music--Xiao Pengyou was published continually for 90 years, except during the Sino-Japanese War (1937-45) and Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

Children’s magazines after 1949: consolidation and specialization

Everything about Xiao Pengyou changed after October, 1949. Under the Guomindang government, the magazine was published in Shanghai by the Zhonghua Book Company.3 Its audience were young urbanites. Although illustrated, it was text-heavy and relatively sophisticated, possibly because the children read the magazine with help from teachers or parents. The contents included stories and poems, cartoons and drawings. Sometimes the magazine included foreign stories, such as 'Pinocchio'; there was little explicit political content.4

Compare the covers of the two magazines [see ⧉source: Children's magazine covers pre-and post-revolution]. On the cover of issue 934, published just before the establishment of the PRC, the central photograph highlights China’s modernity: cars on a major highway. There is nothing political in the decorative borders. Issue 1016, published in 1951, clearly demonstrates the new focus of children’s literature: it is in the countryside, where most people live, and children are actively engaged in the work of the village--hanging up posters about increasing production.

The format and subject matter of children’s magazines changed quickly. From fairy tales and nature facts, the content turned to current issues [see ⧉source: 1951 Children's magazine pages]. The 1951 children's magazine (no. 1022) celebrates land reform under the new government. The 1952 children's magazine (no. 1047), issued during the Korean War, shows the hated ugly American enemy being run out of many countries. Because the readership of Xiao Pengyou was very young, the style and language are simple, with short texts explaining the pictures. The imagery and messages would be clear to the children, because the same themes were presented across many other media: songs, posters, wall paintings and lianhuanhua (连环画 serial picture books). Propaganda campaigns were carefully explained at school and at after-school programmes, such as the Young Pioneers, with children required to participate.

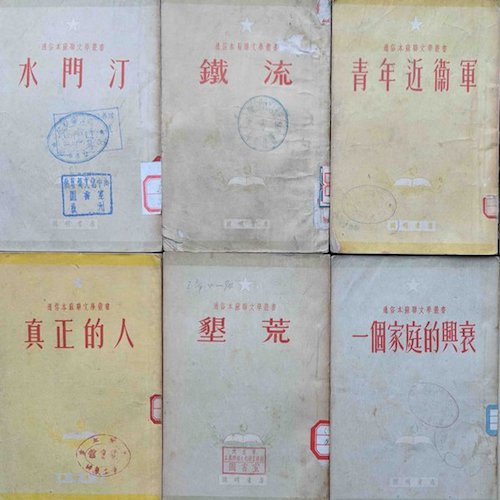

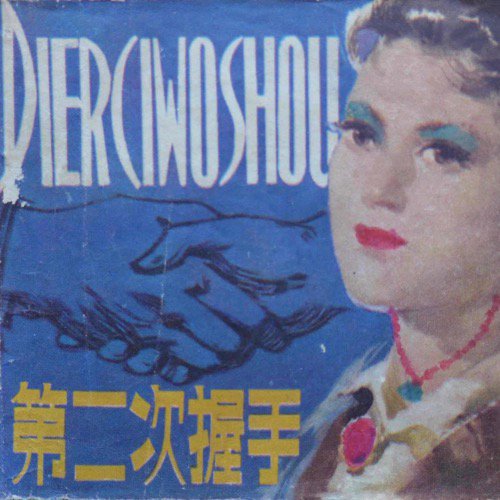

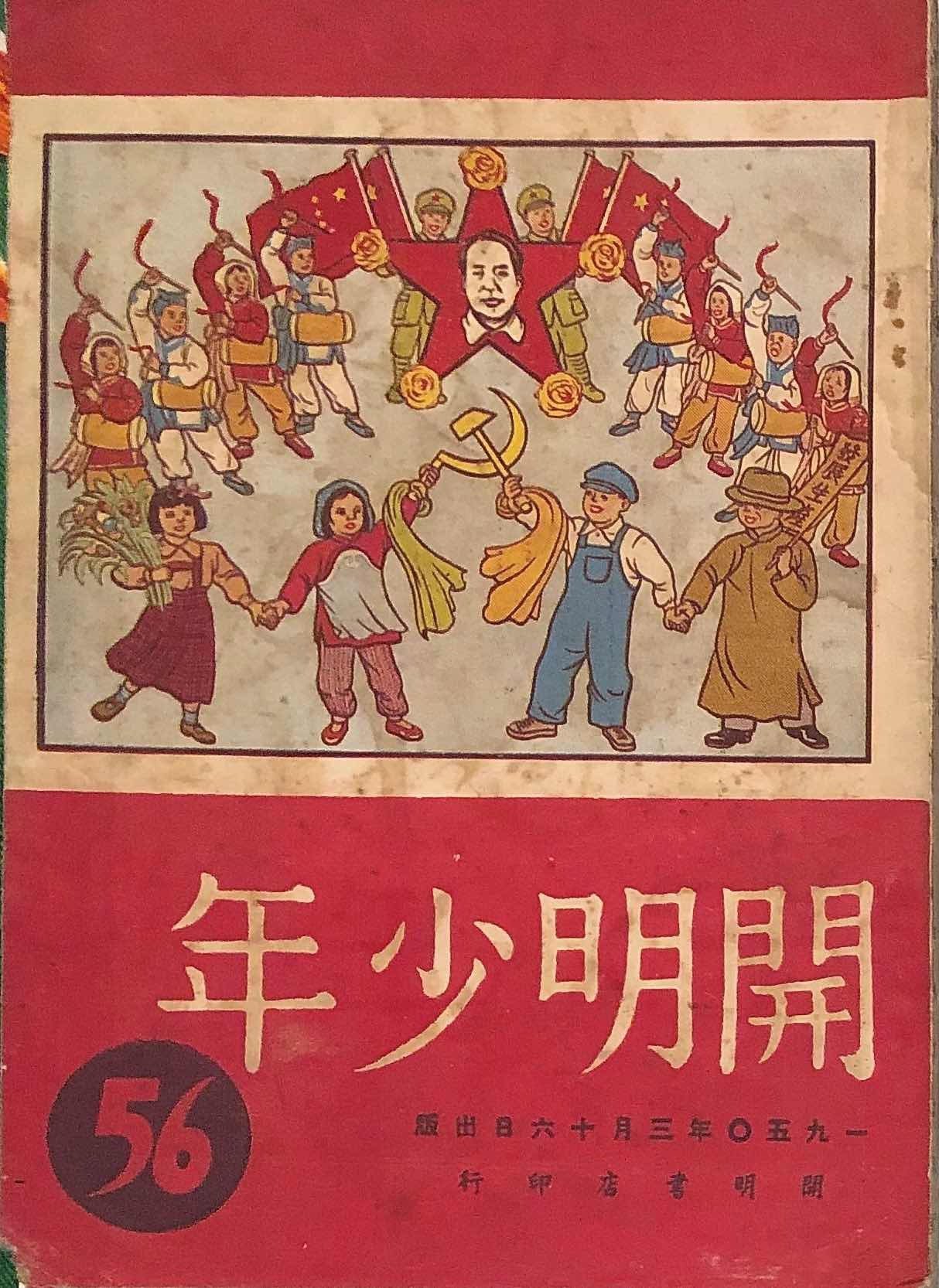

There were numerous other magazines for young children published before and immediately after the Revolution. Two examples are shown here [see ⧉source: 1950 Magazine covers, including the image depicted to the left]. Kaiming Shaonian (Enlightened Youth 开明少年) --the first magazine-- was published by the Kaiming Press, edited by the well-known children’s author, Ye Shengtao 叶圣陶 (1894-1988) and comic artist Feng Zikai 丰子恺 (1898-1975). Kaiming also published the widely distributed monthly, Middle School Student (Zhong Xuesheng 中学生). After 1949, its artwork and subject matter reflected the new society. Here, in the first image, Chairman Mao is shown within a red star,5 its five points adorned with celebratory rosettes. Children of all classes are presented here as adults, dressed as traditional yangge dancers, soldiers and workers. There is even a businessman, whose sign says 'Develop Production.'

The second magazine cover is from a 1950 issue of Xin Ertong Shijie (New Children’s World 新儿童世界), the post-revolutionary incarnation of Children’s World, launched in 1922 by the Commercial Press. The children here, too, are portrayed acting as adults, running a cooperative shop.6 Children’s magazines are also full of juvenile heroes who served in the Sino-Japanese War and Civil War (1945-49).

During the course of the 1950s, the many private publishing houses--national and regional-- were consolidated and centralized under state management. Many children’s magazines ceased publication, generally with a notice or letter addressed to its young readers. An example is the 1954 farewell letter from the editors of Hao Haizi (Good Children 好孩子), a regional magazine published in Shenyang, northeast China [see ⧉source: Letter from the editor of Good Children]. This was part of Manchuria, the first area occupied by Japan (in 1931), so understandably, even more of its contents related to the joyful victory over Japan than nationally-published magazines. Its pages also emphasized Sino-Soviet friendship, given its proximity to the Soviet 'elder brother'. The editors explain that it has been decided to consolidate children’s publishing and there will be new papers for children.7

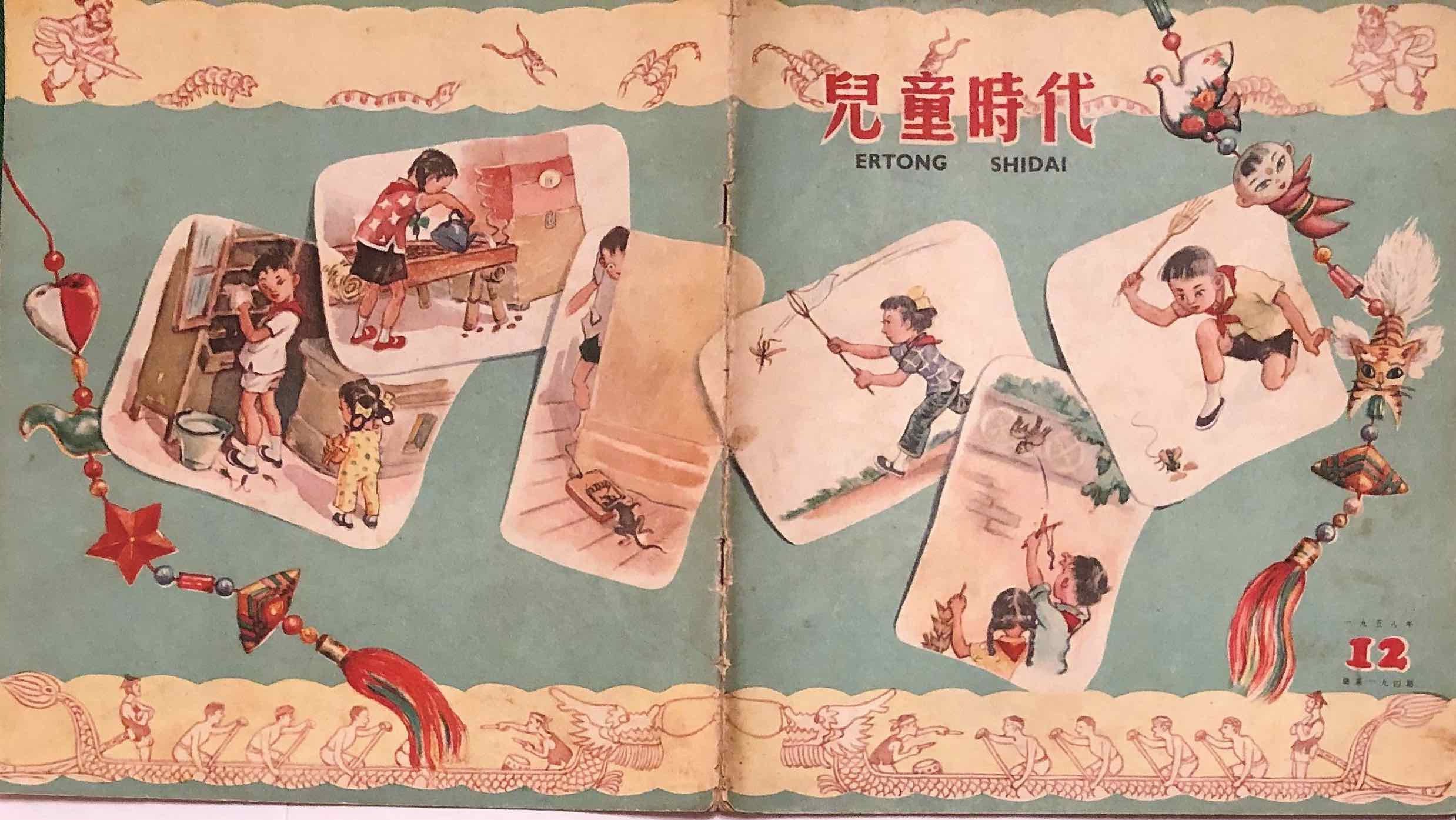

In 1956, the Children’s Publishing House (Shaonian Ertong Chubanshe 少年儿童出版社) was established under the direct control of the Communist Youth League in Beijing. National and regional children’s magazines were further consolidated and centralized. The most widely distributed children’s magazines were the twice-monthly Xiao Pengyou and Ertong Shidai (Children's Epoch 儿童时代 for third and fourth-year primary students) [See ⧉source: International Children's Day & ⧉source: The Four Pests Campaign and the Great Leap Forward]. From this time on, their print runs increased exponentially. Only 8,000 copies of Xiao Pengyou were printed in the early 1950s; by 1956, about 150,000; and by the mid-60s, more than 500,000. They could be received in the mail by subscription, or read in libraries and after-school children’s palaces. Some schools ordered them for additional reading in class. There were other children’s magazines—a high-quality one being Shaonian Ertong Huabao (Young Children’s Pictorial 少年儿童画报). This introduced paintings and woodblock prints by China’s famous artists, as well as specially-created drawings and cartoons for children Most issues of these magazines included cartoons or illustrations by famous artists, such as Feng Zikai (Kaiming Shaonian editor, above) and Zhang Leping (1910-92), a cartoonist best known for his beloved character Sanmao (三毛 three hairs).

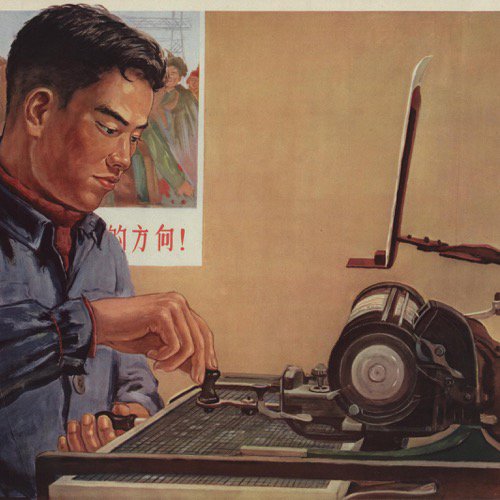

Specialist pictorials provided drawing instruction including this 1955 issue of Shaonian Ertong Tuhua (Young Children’s Drawing 少年儿童图画) [see ⧉source: Drawing manual, Image 1]. Drawing magazines were very precisely compiled: monthly issues were designed for every grade level. Some pages reproduce paintings or propaganda posters. Others give step-by-step directions.

The instructions on the back state that this issue of Shaonian Ertong Tuhua was for students in the first semester of third grade, and its focus was drawing flowers, leaves and insects [see ⧉source: Drawing manual, Image 2]. It emphasizes that teachers must follow the Communist Party Education Committee’s programme outline for drawing. Detailed instructions to teachers were given in separate publications, every month at every level, specifying how to teach each picture in the magazine (seventeen in this issue).

Campaigns and Content

Because they were published frequently, Xiao Pengyou and Ertong Shidai could promote special holidays, current issues or propaganda campaigns. This issue of Xiao Pengyou [see ⧉source: International Children's Day] celebrates International Children’s Day, 1 June 1960. Children are shown from all continents. An issue of Ertong Shidai [see ⧉source: International friendship], for slightly older children, from the same year, carries a more explicitly political presentation of internationalism, reproduced from a painting. After the Sino-Soviet split in 1959, China began asserting itself as a leader of the less-developed world. Here Chairman Mao is at the centre of a gathering of people from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

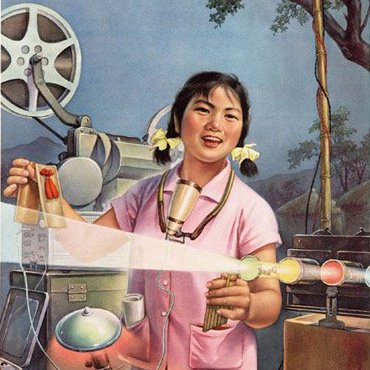

Magazines also rallied children’s participation in longer-term campaigns including the Four Pests Campaign, launched in 1958 to rid the country of rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows [see ⧉source: The Four Pests Campaign and the Great Leap Forward, Image 1, also depicted to the right]. More broadly, magazines celebrated the Great Leap Forward (1958-62), whereby China would surpass the UK in steel production within fifteen years [see ⧉source: The Four Pests Campaign and the Great Leap Forward, Image 2]. The front cover has both traditional and communist iconography, while the back shows the trains, cars, rockets and factories of a very modern China. All media of this period were full of revolutionary propaganda. Imagery was shared among posters, prints, paintings and magazines for children and adults.

Both those campaigns proved disastrous. Policies of the early 1960s focused on economic development and education, rather than politics. Children’s magazines featured traditional stories and folk imagery, along with nature and science activities. However, by the mid-1960s, politics was once again ascendant, as Chairman Mao looked to strengthen his hold on the Party and policy. The February 1966 back cover of Xiao Pengyou [see ⧉source: Education scenes] depicts a group of Young Pioneers studying a photo of Wang Jie 王杰, a youthful hero, whom the children are encouraged to emulate. The slogan across the top of Wang Jie’s photo instructs us that: 'Whatever Chairman Mao says, that’s what we’ll do.'

An inside page of the same issue is about 'traveling schools'. Although the education system had expanded enormously, there still weren’t enough schools in remote regions like Inner Mongolia. This page explains how teachers go from place to place to bring education to the minority peoples. The poem emphasizes literacy and unity under Chairman Mao, who cares about all his children. The other interesting thing here is the use of pinyin romanization. In the early years of the PRC, children’s literature rarely used this romanization. In the 1960s, China expanded the use of simplified characters and romanization to achieve higher levels of language proficiency. Almost no English appeared in children’s magazines until after the Cultural Revolution.

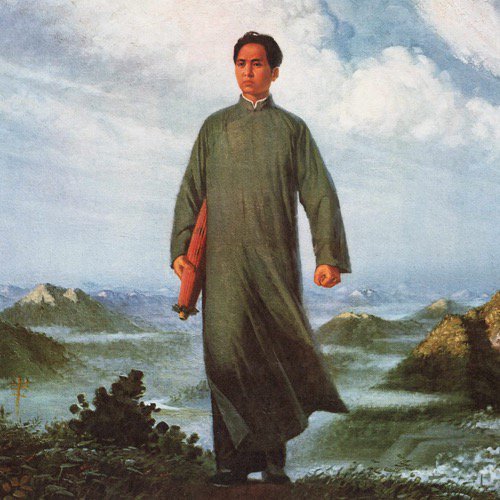

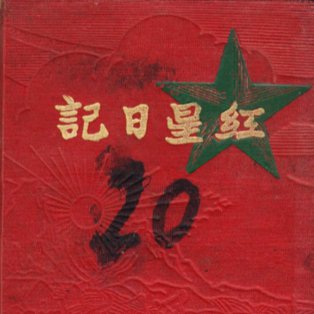

During the Cultural Revolution, Hong Xiaobing (Little Red Guard 红小兵) replaced Hong Lingjin (Young Pioneers 红领巾) [see ⧉source: From Young Pioneers to Little Red Guards, Images 1-3, including the image depicted to the left]. Unlike most children’s magazines, whose production was centralized but with local distribution, Little Red Guard was published in at least eighteen different provinces. The two issues shown here are from Guangdong and Gansu, near the end of the Cultural Revolution. Their imagery and contents mark a return to earlier children’s themes of production, patriotism and unity—nothing like the strident contents of the early Cultural Revolution years. Xiao Pengyou, Ertong Shidai and most other periodicals suspended publication from 1966, reappearing after the Cultural Revolution. The stories and activities of the revived magazines were less political and more educational; presentation was more attractive and diverse. Children’s magazines today are non-ideological in content, and they look very much like Japanese manga. This may change as children’s education has become increasingly political and more explicitly ideological under President Xi Jinping.

Footnotes

See, for examples, Fred I. Greenstein, Children and Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965) and Felicity Ann O’Dell, Socialisation through Children’s Literature: the Soviet Example (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Franklin W. Houn, To Change a Nation: Propaganda and Indoctrination in Communist China (New York and Lansing, MI: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961), 40. China’s population in 1950 was about 542 million.

上海中华书局有限公司 (then spelled Chunghwa Shu-chü), one of the three largest private publishing houses before 1949. Traditionally, Chinese publishers also handled printing and distribution.

Xiao Pengyou (小朋友), no. 924 (23 December 1948).

In communist iconography, the five-pointed star represents, among other things, the five revolutionary classes.

The attitude change toward children—taking them out of their innocent, unworldly lives—began during the Sino-Japan War, when communist partisans encouraged children to participate in the resistance. There was even a wartime magazine aimed at youthful fighters: The Resistance Child (kangzhan ertong 抗战儿童).

The letter reads, roughly: 'Dear Little Friends: Hao Haizi now wishes you farewell. The Youth Organization’s Central Committee is consolidating children’s publishing. For this reason, it has been decided to stop publishing Hao Haizi. There will be two new newspapers for children, and these will be even more helpful for your studying. Hao Haizi published 104 issues, We thank the writers, artists, children’s workers, printers and other comrades for their work[…]

Little Friends! We hope you study hard, build strong bodies, and under the care of Chairman Mao and the Communist Party; under the leadership at school, with your friends and teachers, and with the help of the new children’s newspapers, you become brave, new socialist citizens.

Wishing you progress in your studies, The Hao Haizi Magazine, 15 September.' Unknown Letter from the editor of Good Children (Hao haizi 好孩子), no. 104, 1954. Translation: Mary Ginsberg.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: Magazine Covers Pre- And Post-Revolution

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: 1951 Magazine Pages

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: 1950 Magazine Covers

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: Letter From The Editor Of Good Children

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: International Children's Day

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: The Four Pests Campaign And The Great Leap Forward

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: Drawing Manual

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: International Friendship

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: Education Scenes

- ⧉Image Children's Magazines: From Young Pioneers To Little Red Guards

Further Reading

Cohn, Don J. Virtue by Design: Illustrated Chinese Children's Books from the Cotsen Childrens Library. Princeton: Cotsen Occasional Press, 2000.

Farquhar, Mary Ann. Children’s Literature in China. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc, 1999.

Tillman, Margaret Mih. Raising China’s Revolutionaries: Modernizing Childhood for Cosmopolitan Nationalists and Liberated Comrades, 1920s-1950s. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.