Emily Wilcox, University of Michigan

Summary

Dance was an important part of revolutionary art and culture in China during the Mao period, both as everyday entertainment and to promote Maoist culture internationally. Like other aspects of cultural work, dance had specific ideological and political meanings. Through their use of dance movements, costumes, and props, dancers conveyed new ideas about Chinese society, including ideas about national identity and ethnic groups, views about women, and the nature of Sino-Soviet relations. This biography examines the material culture of Mao era dance through the lens of dance props—objects dancers manipulated in their performances to convey new ideas on stage.Introduction

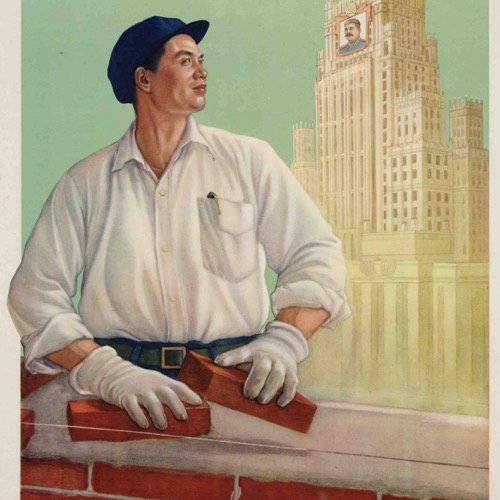

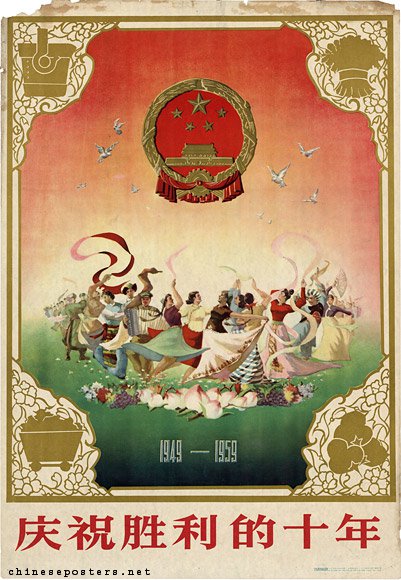

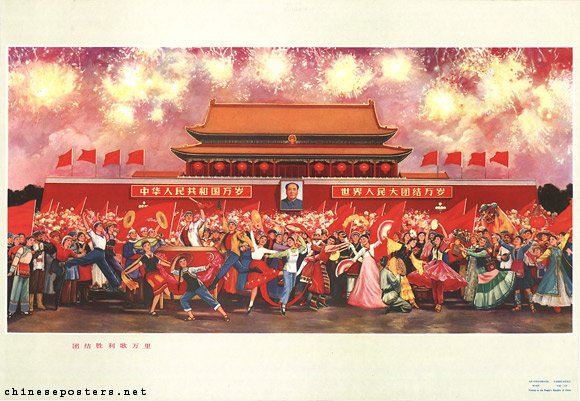

The arts and entertainment were an important part of everyday life in the People’s Republic of China under Mao. Because television was not yet widespread in China at this time, and many people were still illiterate, live performances of music, dance, and theater were among the main sources of entertainment for average citizens, together with film, radio, visual art such as posters, public murals, travelling exhibitions, and crafts such as weaving and embroidery. Even before the PRC was established in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party used performance as a vital tool to promote political messages, recruit soldiers and volunteers, and enact social campaigns such as land reform. After 1949, performance ensembles known as 'cultural work troupes' (wengongtuan 文工团), 'song and dance ensembles' (gewutuan 歌舞团), and 'cultural propagation teams' (wenyi xuanchuandui 文艺宣传队) were established all across the country. Made up of dancers, singers, musicians, actors, set and costume designers, and others interested in the performing arts, these groups used their shows to entertain and teach the masses. Dance, with its upbeat energy and vibrant physicality embodying youthfulness and health, became an essential part of this new revolutionary performance culture [see ⧉source: Celebrate ten years of victory, also depicted to the left]

Why dance props?

Looking back at dance during the Mao era, one of the most ubiquitous features of this period is the use of dance props—objects attached to the body or held in the hand that embellish the dancer’s performance. Today, we often think of these props as a natural component of Chinese dance—fans, ribbons, umbrellas, handkerchiefs, swords, and other objects are common in the repertoires of Chinese dance clubs and performance ensembles in China and around the world. These same props were also widespread in revolutionary Chinese dance created and performed under Mao. In fact, many of the choreographies we regard today as 'traditional' Chinese dance forms—including many types of Chinese classical dance (Zhongguo gudianwu 中国古典舞) and Chinese national folk dance (Zhongguo minzu minjian wu 中国民族民间舞, which includes both Han and ethnic minority styles)—were either first created or first widely popularized in their modern forms during the Mao years as part of the new revolutionary dance culture. By looking at the culture of dance props in China during the Mao era, we can thus better understand the origins of Chinese dance forms widely performed around the world today.

Many dance films from the Mao era have been preserved through the decades and have been uploaded by netizens on free, web-based video sharing platforms [watch ⧉source: Video collage]. By viewing these films, we can see how widespread props were in dance created during this period, because most dance productions recorded on film during the Mao era have them. Moreover, from these recordings, we can also see how integral props were to the diversity of techniques dancers performed. Props were not merely decoration added on to make dances appear more interesting. Rather, they played an integral role in the choreography, making props a fundamental component of revolutionary dance culture.

Learning from folk artists

Dance has been a part of Chinese culture since ancient times, and many of the dance props used in new choreographies created during the Mao era were derived from previously existing performance practices. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Mao and other communist leaders called for the study of folk art as part of the process for creating China’s new national culture. This became known as the 'national forms' (minzu xingshi 民族形式) movement. At the time, cultural workers in and around the communist base areas at Yan’an studied a type of rural northern Han folk performance known as 'yangge' (秧歌, sometimes translated 'rice-sprout songs,' also transliterated 'yangko'), from which they created new political performances, including parades and musical dramas. Common props used in these performances were the waist drum (yaogu 腰鼓), a two-sided drum strapped to the performer’s waist and played while dancing, and colorful pieces of fabric attached to the drum sticks or held in the dancers’ hands [see ⧉source: Celebrating the People’s Republic of China’s national day, also depicted to the left]. In other parts of the country, artists similarly conducted fieldwork on local Han and ethnic minority performance and created new dances based on these materials.

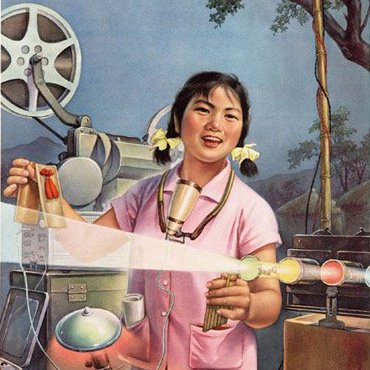

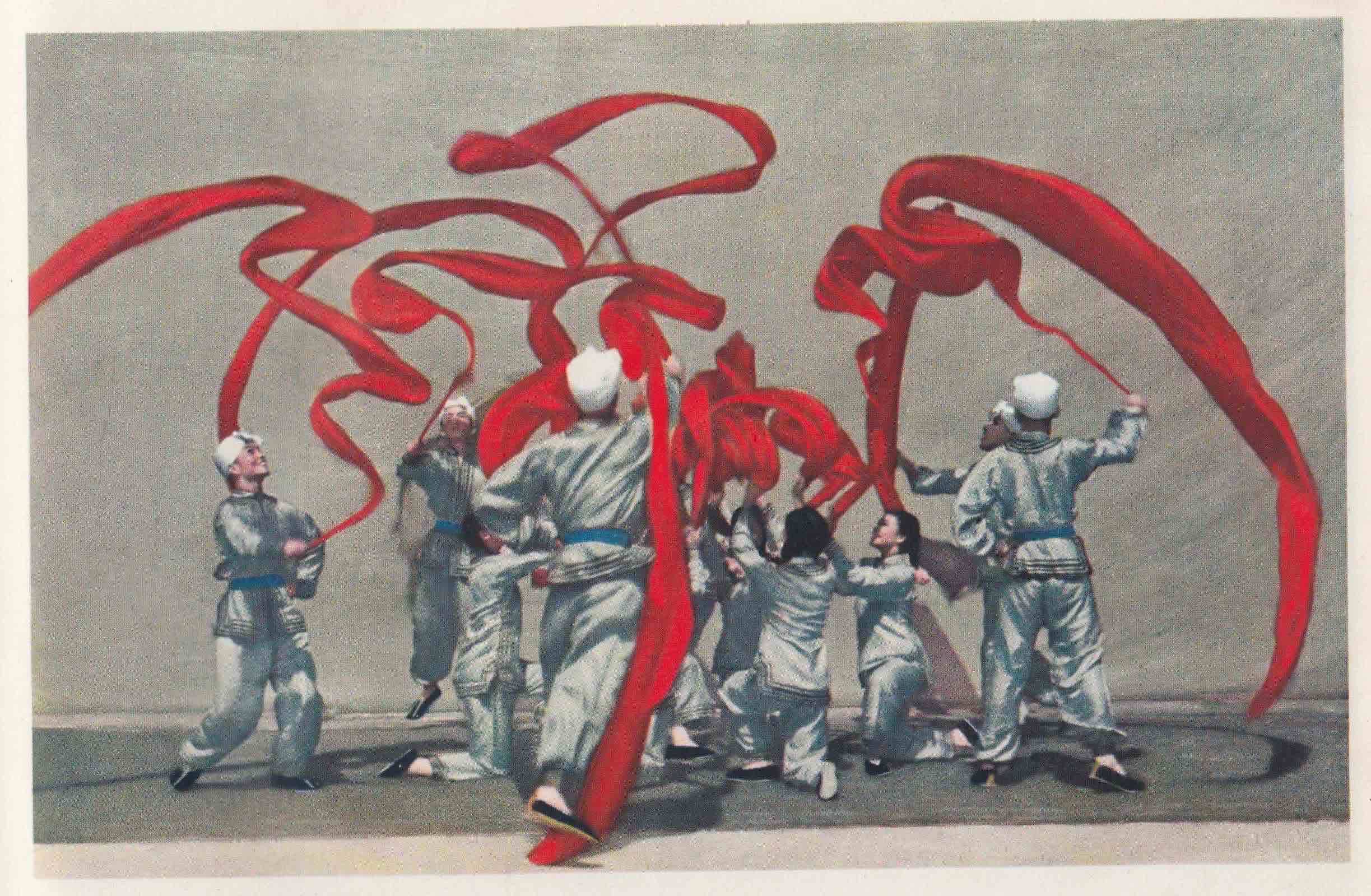

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949, the creation of modern choreography inspired by folk forms continued. Choreographers employed in the newly established performance ensembles and schools were encouraged to conduct field research by learning traditional techniques from folk artists (minjian yiren 民间艺人) and then adapting what they learned into modern stage choreographies [see ⧉source: Learning from folk artists]. The resulting performances were staged in local and national dance festivals, and the best ones were selected to be promoted nationally and internationally, through dance films, handbooks, and tours. Between 1949 and 1962, more than forty of these newly created dance choreographies inspired by folk performance won awards for China at the World Festivals of Youth and Students, international leftist youth festivals that included arts and athletic competitions. Almost all of these dances included props of some kind. The Festivals were an important site of cultural exchange between Chinese dancers and dancers from other countries that were also developing their own styles of modern folk dance, such as the Soviet Union, Hungary, Romania, Poland, India, and North Korea. In 1954, the USSR National Folk Dance Ensemble performed one of these new Chinese dances featuring props—the 'Red Silk Dance'—during their tour to China [see ⧉source: Dance diplomacy 'red silk dance', including the image depicted below to the right].

Creating an iconic dance prop—the Red Silk Dance

How exactly were dances involving props created and popularized in China under Mao? This question can be answered by looking at the making of 'Red Silk Dance' (Hongchou wu 红绸舞), one of the most iconic Mao era dances. A film recording of 'Red Silk Dance' taken in 1963 features six women and six men wearing blue and white costumes styled after the clothing of northern Han farmers. The props used in the dance are long pieces of bright red silk attached to wooden sticks, which the dancers weave through the air in intricate loops, spirals, and zigzagging patterns [see ⧉source: Red silk dance video]. 'Red Silk Dance' first gained national attention in May 1951, when the Changchun City Cultural Work Troupe, the group that developed it, presented it at a national music and dance festival held in Beijing. The piece was so successful that its choreographers were asked to publish an article explaining how they created it. The article, titled 'Silk Dance Study Process,' was then published in the inaugural issue of Dance News (Wudao tongxun 舞蹈通讯) in July 1951 [see ⧉source: Studying silk dance Chinese original &⧉source: Studying silk dance English translation].

From this account, we can glean much information about the processes that went into making such dances and the ideologies surrounding them. Author Xi Zhi describes how members of the cultural work troupe learned from three different types of folk performers, including experts in Peking opera (Jingju 京剧), bengbeng drama (蹦蹦戏, also known as erren zhuan 二人转), and yangge (秧歌). All three of these folk performance forms are popular in Jilin Province, where the cultural work troupe was located. After the performers studied with the folk artists, they incorporated parts of the traditional forms they liked and removed those they found old-fashioned or offensive. Using an ideologically charged term, Xi calls the parts they removed 'feudal poison' (fengjian dusu 封建毒素). Although not specified, the elements removed could have been perceived as too sexually explicit, vulgar, or insulting to marginalized groups such as women and the poor. By blending together silk dances from Peking opera, energetic footwork from yangge, and interactive elements from bengbeng drama/erren zhuan, and seeking advice from different audiences, they finally settled on the final choreography.

'Red Silk Dance' was so popular that the dance was selected to represent China at the Third World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin in August 1951. It was one of only two dances from China that year to win a First Place award in the international folk dance competition, with the other being a Tibetan-style dance. In 1953, a popular handbook was published in Shanghai to teach dancers across China how to perform the dance [see ⧉source: Dance handbook]. By the mid-1950s, it was being performed all over the country.

What props mean

Although Maoist culture emphasized revolution and change, traditional and folk culture played an important role in the vision of revolutionary culture that Mao promoted. This is because 'the folk' (minjian 民间) and 'the people' (renmin 人民) were seen as the originators of revolution in Mao’s worldview, and marginalized communities in particular were to be celebrated in the new revolutionary culture that emphasized egalitarianism and the overturning of class, gender, and ethnic hierarchies [see ⧉source: Dance in propaganda posters, including the image depicted to the left]. This is why there were so many dances during the Mao era that used traditional props adapted from folk performance, especially props related to rural Han society, women’s performance, and minority ethnic groups. These props, combined with costumes, music, and movements learned from local performance, were thought to embody the culture of the revolutionary masses of society, average citizens who came from out of the way places and formerly shunned communities. Using local props was a way of showing that these communities were now embraced as part of a new, more equal, and more diverse vision of Chinese culture.

Props also served as important conduits of traditional knowledge in a revolutionary society that was rapidly changing, while at the same time valued its distinct cultural identity. In order to use props effectively on stage, dancers need to learn physical culture related to the props, such as how to construct them, how to hold and manipulate them in performance, and how to determine which props are appropriate for which types of performance. When a choreographer is creating a new dance, they need to know which type of prop is appropriate to represent the specific region, ethnic group, or character type they want to portray. At the same time, they need to know the technical knowledge for how to manipulate the prop so that it does not appear clunky or awkward in the movement. All of this knowledge requires consulting local performance specialists and spending time studying with folk performance experts. This is why the phrase 'learning from the folk' (xiang minjian xuexi 向民间学习) became one of the most commonly repeated slogans in the dance world during the Mao era. This concept even went beyond the use of props derived from folk traditions. When dancers wanted to create dances that used props from everyday labor, such as farm tools or mechanical equipment, they would visit farms and factories to watch workers and even taking part in the labor themselves to learn how to use the tools correctly. Similarly, when they wanted to create a dance portraying soldiers, they would visit a military compound and practice using guns and grenades. This was all part of the idea of socialist realism—that in order to move their audiences, dance performances should portray real people and real activities, offering a beautified performance based on real life.

Props also served another important purpose in Mao era dance, namely, as sources of creativity. The culture of Maoism encouraged people to constantly come up with new ideas, to be more productive and innovative than they had been in the past, and to create a better life through continuous renewal and change. These values were embedded in the basic idea of revolution. Thus, in dance, this meant that performance ensembles were expected to be actively engaged in the creation of new works at all times. Often, choreographers used props as a way to spark their ideas for this new innovation. Finding a unique type of drum, learning a new way of moving a fan, or discovering objects in daily life that could be turned into dance props helped choreographers come up with new ideas for dance works that they might not have been able to come up with on their own. Thus, the explosion of props in dance during the Mao era is also a sign of the drive toward creativity and the effort to entertain and teach the masses with performances that could be surprising, entertaining, and beautiful in ever new ways.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Celebrate Ten Years Of Victory

- ▸Video Dance Props: Video Collage

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Celebrating The People’s Republic Of China’s National Day

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Learning From Folk Artists

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Dance Diplomacy - 'Red Silk Dance'

- ▸Video Dance Props: Red Silk Dance Video

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Studying Silk Dance Chinese Original

- 文Text Dance Props: Studying Silk Dance English Translation

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Dance Handbook

- ⧉Image Dance Props: Dance In Propaganda Posters

Further Reading

DeMare, Brian James. Mao’s Cultural Army: Drama Troupes in China’s Rural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Holm, David. 'Folk Art as Propaganda: The Yangge Movement in Yan’an'. In Popular Chinese Literature and Performing Arts in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979, edited by Bonnie McDougall. Berkeley: University of California Press, (1984): 3-35.

Hung, Chang-tai. 'The Dance of Revolution: Yangge in Beijing in the Early 1950s'. The China Quarterly vol. 181 (2005): 82-99.

Jia, Anlin 贾安林. Appreciating Chinese national folk dance through key works (Zhongguo minzu minjian wu zuopin shangxin 中国民族民间舞作品赏析). Shanghai: Shanghai yinyue chubanshe, 2006.

Wang, Kefen 王克芬 and Long Yinpei 隆荫培. History of dance development in modern and contemporary China (Zhongguo jinxiandai dangdai wudao fazhanshi 中国近现代当代舞蹈发展史). Beijing: Renmin yinyue chubanshe, 1999.

Wilcox, Emily. 'Dancers Doing Fieldwork: Socialist Aesthetics and Bodily Experience in the People’s Republic of China'. Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement vol. 17, no. 2 (2012).

_____. 'Han-Tang Zhongguo Gudianwu and the Problem of Chineseness in Contemporary Chinese Dance: Sixty Years of Controversy'. Asian Theatre Journal vol. 29, no. 1 (2012): 206-232.

_____. 'Beyond Internal Orientalism: Dance and Nationality Discourse in the Early People’s Republic of China, 1949-1954'. The Journal of Asian Studies vol. 75, no. 2 (2016): 363-386.

_____. 'Dynamic Inheritance: Representative Works and the Authoring of Tradition in Chinese Dance'. Journal of Folklore Research vol. 55, no. 1 (2018): 77-111.

_____. 'The Postcolonial Blind Spot: Chinese Dance in the Era of Third World-ism, 1949-1965'. Positions: Asia critique vol. 26, no. 4 (2018): 781-815.

_____. Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2019. Free open access ebook (https://www.luminosoa.org/site/books/10.1525/luminos.58/).