Ying Qian, Columbia University

Summary

Films are objects whose production requires resources, labor and technology, and whose distribution requires infrastructure. Films also present other objects on the screen. Documentary images, in particular, are supposed to tell truths about the physical and historical world we live in. This biography discusses the substantial resources committed to filmmaking by the young PRC: in one example, the People’s Liberation Army re-enacted four major battles in the Chinese Civil War for the camera. Why was there a perceived need for re-enactment, and what it might tell us about the society where the film was produced?Introduction

In October 1949, soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) Fourth Field Army, who had just recently arrived and settled in their new station near Tianjin, were told that they would again be transferred back to the northeast, where their battalions had fought victorious battles against the Nationalist army a year before. Canons, tanks, and tens of thousands of soldiers were loaded onto trains. Soon the open plains near Jinzhou, where the dust of war had barely settled, were shaken again by cannons and gunfire.

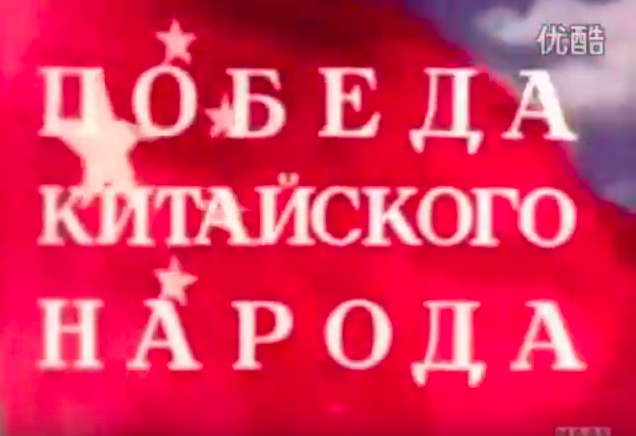

Between autumn 1949 and summer 1950, four major battles marking PLA’s victory over the Nationalists were re-enacted for the purpose of making PRC’s first color documentary Victory of the Chinese People (Zhongguo renmin de shengli 中国人民的胜利 ), a Sino-Soviet coproduction directed by the renowned Soviet filmmaker Leonid Varlamov [see ⧉source: Victory of the Chinese People, see also title screen of Victory of the Chinese People depicted to the left]. This cinematic event was a high-profile undertaking. The making of the film had been suggested by Stalin himself. Chairman Mao personally wrote to General Lin Biao to ask him and his troops for assistance. Real cannons and projectiles were used in the reenactments. Wu Benli 吴本立, veteran CCP filmmaker who participated in this undertaking, confessed to have shed tears watching precious weaponry, having cost lives to acquire from the enemy on battlefields, being used merely for cinematic effect [see ⧉source: interview with Wu Benli & see ⧉source: interview with Wu Benli (Chinese version)].1

Reenactments of battle scenes were not uncommon in the history of documentary cinema, particularly when the actuality, filmed on location during the battle, proved too difficult to produce. However, CCP filmmakers had made actuality films for all of the four battles, at great human cost too: three out of the thirty CCP filmmakers documenting the battle of Liaoshen were killed in action. The Soviet filmmakers had consulted these actualities when preparing for their re-enactments.2 Given that actualities had been made less than a year before, why would it be deemed necessary to film reenactments? Why would the state spend so much money on a documentary film? What could a documentary film teach us about the society in which it was produced?

Film as a Mao-era Object

While films have often been studied and interpreted as 'texts', it’s worth remembering that films are material objects as well. Their production required raw materials, technology and labor. Their distribution must rely on infrastructures of transportation, electrification and exhibition. Founded after years of devastating war, the PRC was short of resources, and the state’s lavish support for the making of Victory of the Chinese People demonstrated its strong commitment to filmmaking.

Cinema was never just a form of entertainment in China. Since the early 20th century, Chinese reformers and revolutionaries had explored cinema’s roles in mass education, propaganda and cultural reform, in their efforts to modernize the country amidst colonial encroachment. In the first decades of the PRC, heeding Lenin’s famous dictum that 'out of all arts for us, cinema is the most important,' the Chinese state nationalized the film industry, brought it under the Party’s leadership, and expanded film production and exhibition. Eight hundred feature films and more than 1700 documentaries were produced by state film studios between 1949 and 1978.3 Total film exhibition venues, including mobile screening units, grew from 648 in 1949 to 115,948 in 1978, among which three fourths were located in the countryside.4

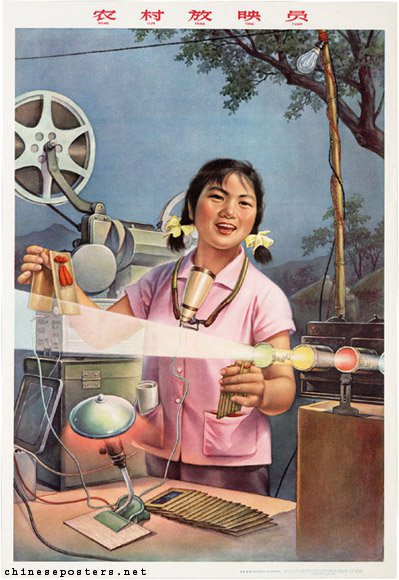

Before 1949, cinema had predominantly served an urban audience. Now it entered the countryside, thanks to a large number of state-trained film projectionists who traveled long distances to screen films to China’s vast rural population. As China’s transportation system was still under-developed in the early PRC, and electrification had not been widely achieved in the countryside, film projectionists became the 'human' infrastructure for film distribution and exhibition. Frequently traveling on rudimentary means of transportation, such as by ox-carts or on foot, they carried film reels, lantern slides, projectors, screens, and power generators, often having to adjust these objects to local conditions. Projectionists not only constantly cared for and maintain these cinema-related physical objects; they also served as presenters and performers, combining story-telling and public lecture with film screenings, to help audience interact with the 'virtual objects' presented on the film screen. [See ⧉source: Film projectionist on poster, also depicted to the right]

Documentary and Concepts of Reality

Documentaries were a staple of Mao-era film screenings. Often shown before feature films as 'starters', they reported on socialist transformations around the country, followed top party leaders in action, and portrayed model workers as new heroes of Socialist China.

Most textbooks on documentary film would credit the British filmmaker John Grierson as the first person to coin the English term 'documentary' and define it as a 'creative treatment of actuality.'5 As a mode of filmmaking, though, 'documentary' had long existed before Grierson’s naming of it in 1926. Labeled differently in different languages and societies, documentary as a practice was never uniform and always changing, but by and large it was a mode of cinema with a certain truth claim, expected to be based on facts and tell true stories.6 Critics have argued against naïvely treating documentary as a transparent window into reality. The filmmaker and critic Trinh Minh-ha has gone so far as to state that 'there is no such thing as documentary.'7 What she meant was that documentary, naively understood as providing unmediated access to 'reality' or 'truth,' does not exist. Our access to realities that matter is always mediated and determined by the political, epistemological and technological possibilities of our times. As object, technology and practice, documentary draws from and contributes to the prevailing epistemologies of the society where it’s produced. It gives us an opportunity to examine what was understood as 'real' and 'true' in a given society, and how media technologies such as cinema has contributed to this construction.

As the PRC’s first major documentary, the Sino-Soviet co-production Victory of the Chinese People opened in September 1950, in time to celebrate the first anniversary of PRC’s founding [see ⧉source: screening announcement in Guangming Ribao]. Audience filled cinemas: in Shanghai alone, around 200,000 tickets were sold in the first five days when they became available.8 Countless essays were published to celebrate the film’s artistic achievements, though few, if any, discussed why re-enactments were necessary in this case [for an example of the documentary's reception see ⧉source: Ministry of Labour Study Group discusses Victory of the Chinese People].

To understand the perceived necessity of these battle re-enactments, let’s take a look at the broader discourse around documentary at the time. Between 1952 and 1953, PRC’s newly founded journal Film Art in Translation (Dianying yishu yicong 电影艺术译丛) published numerous translated essays by Soviet filmmakers and critics on documentary. These essays were originally published in the Soviet Union in 1950 and 1951, therefore reflecting the Soviet discourse around the time that Victory of the Chinese People had been produced.9 The biggest target of criticism in these essays was 'documentalisms', the idea that by simply pointing the camera at the visible world, one would get an 'objective' depiction of reality. This was a dangerous idea, warned the critics, because 'superficially gliding over the appearance of reality… was no less toxic than fabrication.'10 For example, one scene in a Soviet documentary Fishermen of the Caspian (dir. Y. M. Bliokh, 1949), in which a fishermen’s team was awarded a red flag for winning a productivity competition, 'was shot with low light, as if it had been something very common, meaningless, and ordinary. The narration was vague and hurried… without profoundly showing the essence of this event, and the great meaning of socialist competition, which, as we know, is the basis of labor relations in the Soviet society.'11 In another example, a leader of a collective farm made an arrogant appearance in a documentary, but does this truly manifest his 'essential' character? It could simply be an 'accidental and secondary character that only became manifest in the particular environment created by the act of filming.'12 In both cases, appearances captured by the camera were inadequate in revealing the 'essential' qualities of events and people, due to contingencies during the filmmaking, such as inadequate light and accidental behavior in front of the camera.

A common feature shared by these essays was a fundamental distrust of the visible world, which was considered superficial, messy, and full of accidentals that would confuse and mislead. The task of the filmmaker, therefore, was not to record but to re-order the visual world: to discern the important from the trivial, grasp the essential from the contingent, so that they could render visible a reality more real than the observed world. To achieve this, the documentary script was seen to have great importance. Writing as a form of conceptualization could make order out of the raw materials of the visible world. Writing a documentary script before filming can help filmmakers think carefully about sound, color, rhythm and composition, to envision a unified aesthetics for the event before it takes place.13

It’s worth noting that Soviet filmmakers hadn’t unanimously supported documentary dramatization. In the 1920s, the avant-garde Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov had advocated kinopravda (Кино-Правда, 'kino-truth'), which sought to document 'life caught unaware' with the mechanical (and therefore more objective) 'kino-eye.' Calling film dramas 'surrogates for life,' Vertov believed that only footage from unrehearsed everyday life could serve as 'a thermometer or aerometer of our reality.'14 He was also opposed to documentary scripting: 'Kinopravda doesn’t order life to proceed according to a writer’s scenario, but observes and records life as it is, and only then draws conclusions from these observations.'15 Vertov didn’t distrust the visible world, on the contrary, it was exactly in observable world that reality and truth would reveal themselves, not directly to the camera, and never in their totality, but through fragmentary observations that when put together revealed contradictions, formed multiple perspectives, and entered into dialectical relationships with each other.

Victory of the Chinese People and Documentary Dramaturgy

How to approach the visible world, gain knowledge about its underlying realities, and express it in visual means? This is a genuine epistemological problem facing documentary filmmakers, but it’s not the only problem they must solve. As documentary cinema became increasingly used for propaganda purposes in the 1930s and during WWII, filmmakers were pressured to tell simpler and clearer stories for effective propaganda. The open-endedness of social inquiry and the totalizing tendencies of propaganda formed a central tension within documentary practice everywhere, and not just in Soviet Union or China. To which end would this art turn depended on political imperatives of the time.

In the Soviet Union, Vertov’s approach was criticized since the early 1930s, when Stalin tightened control of art production. Dramatization, including staging and reenactment, became a dominant method to create strong and unambiguous revolutionary iconographies that could circulate better as propaganda. In China, documentary as a form of filmmaking had grown substantially during the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Civil War (1946-1949) to answer needs for war mobilization. After the founding of the PRC in 1949, documentary continued to serve as an important means of propaganda carrying messages from the state to the population. While Chinese filmmakers had occasionally employed dramatization in documentary filmmaking prior to 1949, they learned to appreciate the efficacy of documentary dramaturgy when collaborating with Soviet filmmakers on Victory of the Chinese People.

The Chinese filmmakers learned that the black-and-white actuality images, shot in the midst of war, were too lack-luster and uncontrolled to serve as the foundational images for the new PRC. Victory of the Chinese People, shot in color and conceptualized and choreographed by Varlamov, one of Soviet Union’s most skillful documentary scriptwriters, served as a corrective. Compared to the actualities made during the war [See ⧉source: Million Heroes Cross the Yangtze], Victory of the Chinese People consistently featured larger scales of action, achieved by mobilizing a larger number of people and more frequent use of unobstructed and continuous panorama shots. It was also more attentive to the organization of collective action and gave more screen time to the military leadership. Perhaps the most important was the fact that filmmakers of battlefield actualities had far less control of what they could film, and therefore, the film was open to chance happenings, digressions and interruptions. The re-make, on the other hand, was fully choreographed: dramatic and dynamic, it allowed no distraction from the forward thrust of the PLA’s relentless march to victory. By shunning actuality footage and resorting to expensive re-enactments, this documentary created a fantastic world on the screen, one that would yield its truth without ambiguity, in totality.

Victory of the Chinese people left lasting impact on Chinese documentary. The undertaking of this film imparted a certain attitude towards the visible world, understanding it as inadequate, misleading and in need of rectification, which, in part, paved way for bolder staging in later periods. It was this attitude towards the observable world that documentary filmmakers in the post-Mao years of the 1980s tried to overcome, with their stated interest in the phenomenological reality of immanence, rather than in essential realities determined a priori, and external to the observable world.

Footnotes

Fang Fang, Historical Development of the Chinese documentary (Zhongguo jilupian fazhanshi 中国纪录片发展史) (Beijing: Zhongguo xiju chubanshe, 2003), 215.

Ibid., 215.

Yomi Braester and Tina Mai Chen, 'Film in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979: The Missing Years?' Journal of Chinese Cinemas v.1, no. 5 (2011): 5.

Huang Mei 荒煤, 'The Rapid Development of New China’s Cinematic Enterprise' (Xin Zhongguo dianying shiye de xunsu fazhan 新中国电影事业的迅速发展) People’s Daily, 30 October 1959.

John Grierson, 'Flaherty’s Poetic Moana,' New York Sun, 8 February 1926; reprinted in Lewis Jacobs (ed.), The Documentary Tradition, 2nd ed. (New York: Norton, 1979), 25.

Bill Nichols, Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), 116.

Trinh Minh-ha, 'The Totalizing Quest for Meaning', in When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics (New York and London: Routledge, 1991), 29.

Unknown, 'Victory of Chinese People in cinemas in fifteen major cities including Beijing and Tianjin from today' (Zhongguo renmin de shengli jinri qi zai Jingjin deng shiwu dachengshi shangyan《中国人民的胜利》今日起在京津等十五大城市上演) People’s Daily, 29 September 1950, 12.

For the evolution of documentary and newsreel cinema in the Soviet Union, see Graham Roberts, Forward Soviet!: History and Non-fiction Film in the USSR (London: I.B. Tauris, 1991).

I. Nazarov, 'The realism of documentary' (Jilupian zhong de zhenshixing 纪录片中的真实性), Film art in translation (Dianying yishu yicong 电影艺术译丛) no. 1 (1953): 53.

Ibid., 58.

Ibid., 57.

R. Grigoriev. 'A discussion of documentary film scripts' (Lun jilupian de juben 论纪录片的剧本), Film art resources (Dianying yishu ziliao congkan 电视艺术资料丛刊), no. 3 (1952): 11.

Dziga Vertov, 'The Essence of Kino-Eye' (1925), in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, trans. Annette Michelson (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1984), 50 and 48.

Dziga Vertov, 'On Kinopravda', in Kino-Eye, 45.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ▸Video Documentary Film: Victory Of The Chinese People

- 文Text Documentary Film: Interview with Wu Benli

- ▤Pdf Documentary Film: Interview with Wu Benli (Chinese version)

- ⧉Image Documentary Film: A Film Projectionist In Action

- 文Text Documentary Film: Screening Announcement for Victory of the Chinese People

- 文Text Documentary Film: Ministry of Labour Study Group discusses Victory of the Chinese People

- ▸Video Documentary Film: Million Heroes Cross The Yangtze

Further Reading

Berry, Chris, Lu Xinyu and Lisa Rofel (eds.). The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010.

Braester, Yomi. 'The Political Campaign as Genre: Ideology and Iconography During the Seventeen Years Period'. Modern Language Quarterly, 69 (1), (2008): 119-140.

Pang, Laikwan. The Art of Cloning: Creative Production During China’s Cultural Revolution. London: Verso Books, 2017.

Qian Ying. 'Crossing the River Twice – Cinematic Re-enactments and the Founding of PRC Documentary.' In Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinema, edited by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Cheng-yin Chow Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013: 590-609.

Wang, Zhuoyi. Revolutionary Cycles in Chinese Cinema, 1951-1979. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Zhou, Chenshu. 'The versatile film projectionist: how to show films and serve the people in the 17 years period, 1949-1966'. Journal of Chinese Cinemas vol. 10, iss. 3 (2016): 228-246.