Jennifer Altehenger, University of Oxford

Summary

As objects of ideology, design, science, economic planning, consumption, and everyday use, chairs and stools can reveal much about politics, society, culture, and daily rhythms during the Mao period and later Reform Era. This biography examines the role of chairs and stools in the transition to socialism and industrial development after 1949. It illustrates how these furniture items were designed, how they became part of the CCP's planning process including the five-year plans, and how design and materiality were shaped by momentous events such as the Great Leap Forward.Introduction

Chairs and stools, together with benches and other kinds of seating, were part of people's everyday life in the People's Republic of China under Mao. Most people owned or rented such furniture items, or received them as part of their accommodation in work units or communes. Furniture was also to be found in factories, government and party offices, communal halls, kindergardens, schools, and universities, hospitals, hotels, worker's palaces and cultural palaces, and all sorts of other public, communal and work spaces. Compared with the amounts of furniture that surrounded citizens of post-war industrialised societies in Europe, the US, and even the Soviet Union during this time, however, public and private spaces in China often did not have a lot of furniture between the 1950s and 1970s. A family that owned several pieces of furniture would have been considered well off, especially if they also owned some of the other coveted consumer items such as a sewing machine. Towards the end of the Mao Era, the ideal amount of furniture a young couple should own was known as the so-called '36 feet' or 'legs' (36 zhi jiao or tui 36只脚 or 36 只腿) - including four stools, a table, bed, sidetable, wardrobe, and chest of drawers - [See ⧉ source: Image of the '36 feet']. A one- or two-seater sofa was a luxury that few could afford or get access to, and owning a sofa could - and at times did - put its owner at risk of being labelled a bourgeois or capitalist. As objects of ideology, design, science, economic planning, consumption, and everyday use, chairs and stools can therefore reveal much about politics, society, and daily rhythms during the Mao period.

Why look at chairs and stools?

In the years following the establishment of the PRC in 1949, the government sought to standardize furniture by creating guidelines for design, measurements, manufacture, and material use. Chairs came in small and large sizes, many were foldable and some had a bit of upholstering (though not enough to classify them as sofas). Both chairs and stools sometimes had ornamental designs. Mostly though they were plain with a focus on functionality. Depending on where one lived and worked, they were mostly made of wood or bamboo, the latter being common in southern parts of the country. Chairs and stools partly or fully made of metal and later plastic coverings became increasingly widely available between the 1960s and 1970s.

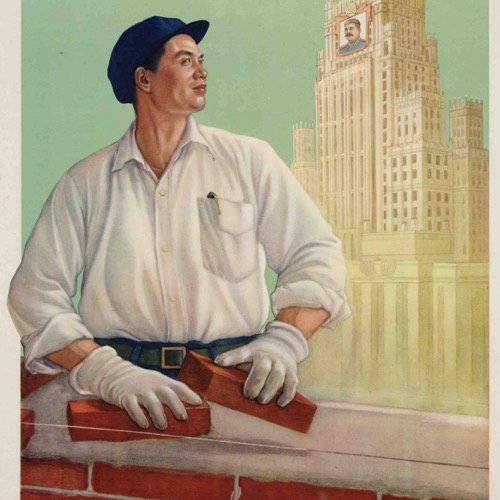

This object biography examines two iconic seating types that -- although both predated the PRC and had long been popular objects of daily use -- came to be representative for the kind of furniture one had during the Mao period. One is the little square stool (dengzi 凳子), which was in widespread use across the country, in rural and urban areas alike. The other is the wood chair (yizi 椅子), often found in local party and government offices and also in urban homes where it was a coveted form of living room seating albeit less prominent than stools and benches. Chairs were much less common in rural areas. In northern rural areas, for example, houses often had a so-called huokang (火炕), a raised platform often made of bricks that served multiple purposes as storage heating, bed, and seating space for daytime living, work, and meals. In these spaces, stools were far more versatile. Both the stool and the chair frequently featured in propaganda images idealising home and work life in 'New China' and thus became part of the visual repertoire representing CCP ideology and rule. [See ⧉source: Furniture in propaganda posters, including the image depicted to the left]

The story before the founding of the PRC

Prior to 1949, furniture was mostly designed and made across the country in thousands of small workshops and furniture companies (many family-run), in midsized to large furniture factories, and in arts academies and institutes. Local artisans and carpenters often devised their own techniques and designs depending on which materials they used and depending on which tools they owned, could borrow or rent [See ⧉source: Pre-49 carpenter workshops in Beijing]. More affluent customers could buy fashionable and often Western-style furniture in the limited number of urban department stores that had opened in previous decades in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, and other predominantly coastal urban centres. Most people, however, acquired pieces from salespeople who travelled through neighbourhoods and districts, from peddlers on local markets, or they went to a local shop that had a showroom upfront and a carpentry workshop at the rear. One could also commission furniture items to individual specifications: a popular option that was not necessarily more expensive. Change came during the 1950s. Private furniture workshops were mostly shut down or merged into joint state-private managed or state-owned businesses. Urban furniture production was further mechanized and new major wood processing plants were established which also produced large quantities of furniture, especially chairs, stools, tables, wardrobes, beds, and other basic items. Still, the vast majority of the trade nonetheless remained semi-mechanized or fully dependent on manual labour until the late 1970s, despite the party-state's occasional attempts to increase the country's production capabilities for basic everyday furniture.

Plans and designs

Design was an important element of urban furniture production. Space was tight in many cities. People who lived in old buildings often had little space for furniture. New housing, too, was not very spacious. People who moved into newly built housing often had the problem that the furniture they already owned was too bulky for their new homes. As one reader, who was otherwise excited about new worker accommodations, explained in an article in the CCP's national daily broadsheet People's Daily (Renmin ribao 人民日报) in September 1956: 'If you put in a bed, you cannot have a table. If you have a table, you cannot fit in a chair and a cabinet; not to mention other larger furniture'.1 Similar problems existed in party and government offices, in dormitories, and other spaces.

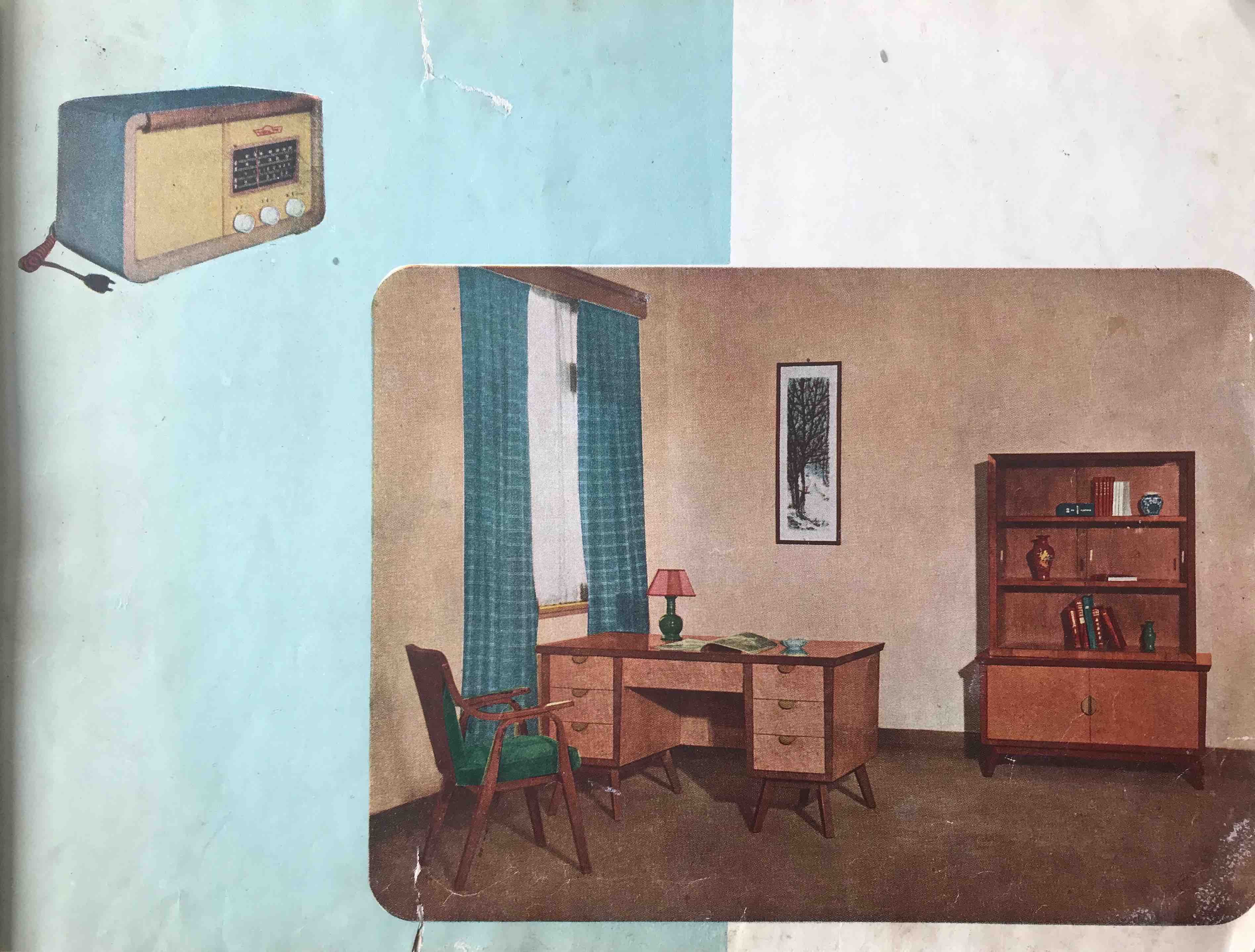

Designers and carpenters working in urban factories, major research institutes such as the Central Academy for Craft and Design in Beijing, large universities such as Shanghai's Tongji University, and provincial-level design research institutes searched for solutions and published on the question how to create designs suitable for new spaces and for a society in the process of transitioning to socialism. Good furniture, magazine articles explained, would be 'functional, economical, and beautiful', of lasting quality but also designed in such a way that it would be cheap to produce industrially in large quantities and affordable for the wider population. Calls for functional, economical, and beautiful furniture became part of the Great Leap Forward that was supposed to fast-track China to material plenty for all. In 1958, during the Great Leap, the Central Academy for Craft and Design set up a furniture research department. In late 1959, the national Ministry of Forestry and the Beijing Timber Mill put some of the prototypes developed in mills in Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin and Guangzhou on display in an exhibition in a modernist new showroom on the mill's grounds. A catalogue of the exhibition circulated after the event showed chic chairs and tables. Many of the items on display were constructed in the modernist fashion popular also in other socialist Eastern European countries after 1956 and Western liberal-democratic countries [See ⧉source: 1960 Beijing Timber Mill furniture exhibition catalogue, including the image depicted to the right].

How to best design a chair was a question of aesthetics and functionality, as well as of human behaviour and labour productivity. Scientific research and calculations promised to provide solutions for design. Good design, in turn, promised to lead to happier people and higher production outputs. People's everyday lives were thus to be focused fully on raising productivity and increasing production. A well-designed chair would allow someone to sit and work long hours without tiring easily [see ⧉source: Measurements for seating]. The national magazine of China's Architectural Association, the Architectural Journal (Jianzhu xuebao 建筑学报), featured discussions about how to best design chairs and other furniture (made of wood, bamboo or rattan) together with technical drawings and measurements. One article suggested that chair height, including the length of backrests and seating area, should be calculated on the basis of the average man who was presumed to be ca. 169 cm tall. To fit this average man, the article advised that chairs should be about 90cm high (including the backrest), with a seating height of 40cm. Chairs built using these measurements would not occupy too much space in any room. A standardised measurement would also make it easier to mass-produce the same chair in customised factory lines, making production cheaper, and making it easier to control the quantity and quality of materials used.

As this example demonstrates, resource maximisation mattered. The government was adamant that furniture production should not waste precious resources. Furniture was an essential of daily life, but it was also a consumer good. It was supposed to be available to China's citizenry, but not in excessive amounts that the CCP considered unnecessary for daily life. And furniture production should not impede the larger project of socialist construction. Ideally, a chair would need few materials, including a reduced amount of nails and glue. If possible it should be made of recycled or waste materials that were not needed for other industrial work and construction projects. As in other countries at the time, scientists, materials experts, and engineers experimented with different materials for furniture production. So-called 'man-made boards' (renzaoban 人造板) and other man-made materials such as plastic became the ideal material for furniture production in general and chairs in particular: Particleboard (also known as chipboard), made of wood shavings and other wood remnants, was the most common man-made board during the 1960s. Later, during the second half of the 1970s, fibreboard - a board made of cellulose invented in the US in the late 19th century and manufactured as prototypes in the PRC since the late 1950s - became the other favoured material.

Everyday life

Political ideals of how much furniture should be produced and available, and how it should be produced and designed, diverged greatly from the reality of people's everyday material lives. It could be extremely difficult to buy chairs and the options for acquiring pieces changed over time. In the early 1950s, many urban residents still purchased their chairs and stools in local private stores, from peddlers, or directly from the factory. During the 1960s and after, one could buy chairs and stools in state-owned furniture stores. But the amounts of chairs available could be limited as shortages were common. Work units also provided chairs, stools, and other furniture items and in some cases people rented their furniture. When chairs were allocated or let, their temporary owners received booklets stating what kind of chair and other furniture they had received, and how much they paid per month [see ⧉source: Furniture rental booklet].

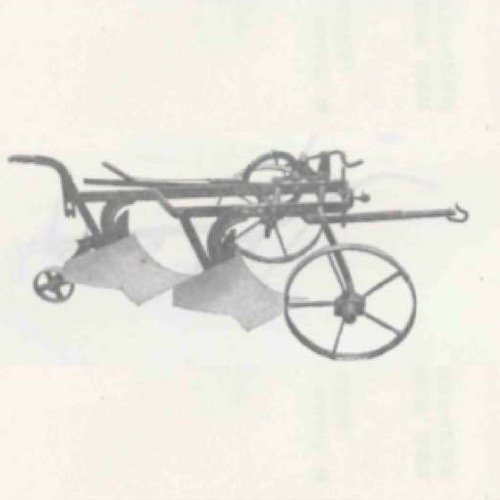

A third way to obtain furniture was to make it oneself, from new materials or by refurbishing old furniture or recycling old materials. CCP authorities were quite supportive of DIY (Do it yourself) furniture making, particularly for use in people's homes and local work units that did not have easy access to provisions. They hoped this would ease pressure on the market for new furniture and ensure that work units, schools, party-state bureaus and other public bodies had first access to it. Amateur carpenters could find specifications and measurements for new chairs and stools in furniture making manuals. Many of these manuals could be either acquired in bookstores, accessed in local libraries, or they were internally published by local factories for local circulation and use in other carpentry workshops and by individual carpenters [see ⧉source: DIY furniture manuals]. This was a popular choice for people who could acquire the necessary material and either owned or could borrow tools. The ideal of DIY carpentry was of course reuse of second-hand materials, but many of these chairs and stools ended up being built from materials acquired on the black market or through trade outside of the official channels of material distribution.

Because people on average had little furniture, the few items they possessed could become important to how they remembered the Mao period. Wu An'na from Guangzhou, for instance, recalled in a New York Times article how she always took a small stool along to struggle sessions during the Cultural Revolution.2 Because she was still young, she would stand on the stool to better see what was happening on the stage. She recalls her response when her father's colleague, while being struggled against, cried out: 'I was terrified and, picking up my stool, ran away. In my panic I slipped and the stool crushed the bone of my right small finger.' Wu's recollection illustrates that holding on to the stool was important and instinctual, but it also became a source of long-term pain and a painful memory. [See ⧉source: Wu An'na's recollection in the New York Times]

Into the reform era

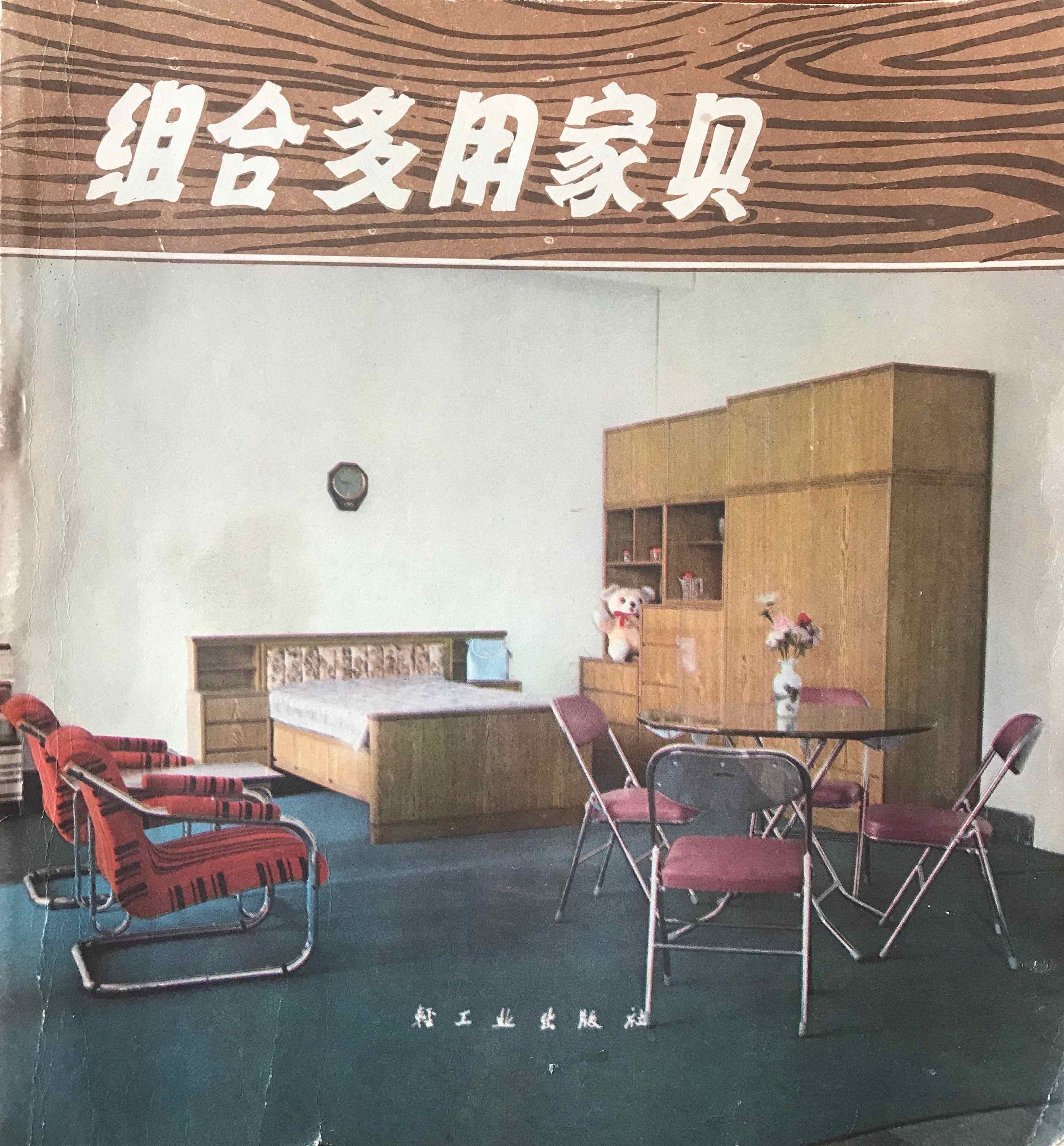

People's material life changed visibly in the course of the late 1970s and 1980s. Chairs and stools both remained staple furniture items in homes, and chairs in particular came to symbolise material improvements in urban residents' lives. When couples' married, they often acquired their first furniture items, which many stores now sold as sets [See ⧉source: Mid-1970s furniture drawings, and ⧉source: Late 1970s drawings of modular multi-purpose furniture, including the image depicted to the left]. During this time, many of the designs and material innovations first discussed during the late 1950s and 1960s moved beyond prototypes into regular manufacturing. To understand the changes that Deng Xiaoping's policies of 'reform and opening' meant for material culture in China, we therefore need to look across 1978 and connect the Republican, Mao, and post-Mao periods.

Footnotes

Zhang Qingming 张清明, 'Shengchan huodong jiaju (生产活动家具)', Renmin Ribao (People's Daily), 7 September 1956, 2.

'Readers Respond: The Cultural Revolution's Lasting Imprint', New York Times, 16 May 2016.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Image Of The '36 Feet'

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Furniture In Propaganda Posters

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Pre-1949 Carpenter Workshops In Beijing

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: 1960 Beijing Timber Mill Furniture Exhibition Catalogue

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Measurements For Seating

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Furniture Rental Booklet

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: DIY Furniture Manuals

- 文Text Chairs And Stools: Wu An'na's Recollection In The New York Times

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Mid-1970s Furniture Drawings

- ⧉Image Chairs And Stools: Late 1970s Drawings Of Modular Multi-purpose Furniture

Geography

In autumn 1959, the Ministry of Forestry organised an exhibition of new engineered woods and furniture in the comprehensive wood usage showroom (mucai zonghe liyong zhanlanshi 木材综合利用展览室) on the grounds of the Beijing Timber Mill in Fengtai district.

Designers and carpenters at Tongji University contributed to the domestic discourse on furniture design.

In 1956, the opening ceremony for the newly founded Central Academy for Arts and Crafts (中央工艺美术学院) was held in Mashen Temple (马神庙) in Haidian district. The following year, in 1957, the Academy came under the leadership of the Ministry of Culture and moved to Chaoyang district (朝阳区东三环中路34号).

In 1999, the Central Academy for Arts and Crafts merged with Tsinghua University and was renamed Central Academy for Arts and Design Tsinghua University. It is now located inside Tsinghua University in Haidian.

Timeline

Further Reading

Altehenger, Jennifer. ‘Sozialistische Möbelkultur: Das Pekinger Sägewerk und die Ausstellung zur umfassenden Holzverarbeitung, 1959’. In Vom Wesen der Dinge: Realitäten und Konzeptionen des Materiellen in der chinesischen Kultur, edited by Grete Schönebeck and Philip Grimberg. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2019.

Betts, Paul. ‘Building Socialism At Home: the case of East German interiors’. In Socialist Modern: East German Everyday Culture and Politics, edited by Paul Betts and Katherine Pence. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2008, 96-132.

Chernyshova, Natalya. Soviet Consumer Culture in the Brezhnev Era. London: Routledge, 2013.

Clunas, Craig. Chinese Furniture. London: V&A Publications, 1997.