Stefan Landsberger, Leiden University, Institute of Area Studies

Summary

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) is inextricably bound up with images of uncountable numbers of propaganda posters, and Red Guards. Poster production reached a climax during the period, turning the event into a media spectacle. Mao Zedong’s image graced millions if not billions of these posters, dominating all aspects of life. After Mao’s death in 1976, his veneration came to a halt. However, the new leadership realized that doing away with Mao was impossible. Over the years, posters have been replaced by television and online propaganda. With Mao’s likeness gracing Chinese banknotes, 'Grandpa Mao' now has become a sought-after commodity.Introduction

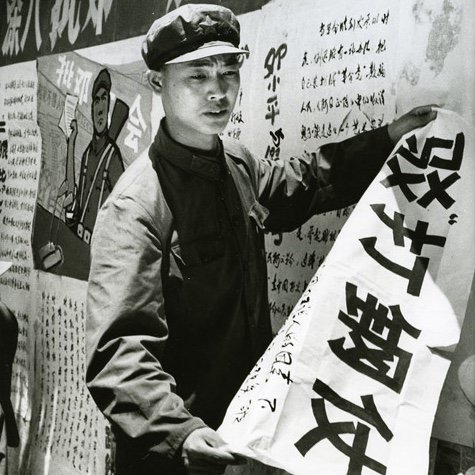

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) is inextricably bound up with images of uncountable numbers of propaganda posters, big-character-posters and Red Guards committing all sorts of violent acts [see ⧉source: The 3 July and 24 July proclamations are Chairman Mao's great strategic plans]. Admittedly, the production of propaganda posters reached a climax during the period, turning the event into a media spectacle. Yet, the use of propaganda art was not new in China. Throughout its long history, the Chinese political system has actively presented and spread its ideas of correct behavior and thought. It used paintings, songs, high- and low-brow literature, stage performances and other artistic forms, such as New Year prints, to make sure that the cultured elite and illiterate masses behaved as they should. After 1949, propaganda posters played a major role in the many campaigns that mobilized the people, and became the favored medium for educational purposes; they could easily reach the large number of illiterate Chinese. The government employed the most talented artists, many of them former commercial designers, to design the posters.

The official Mao portrait

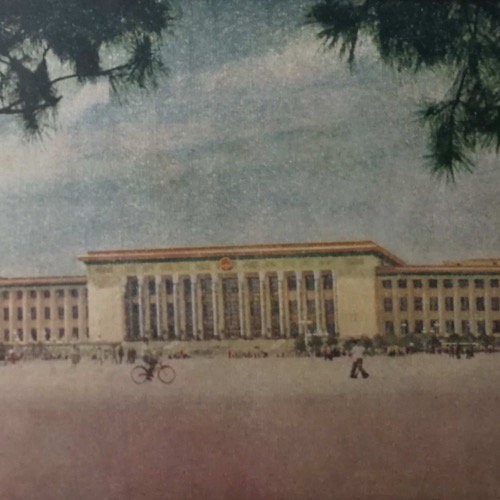

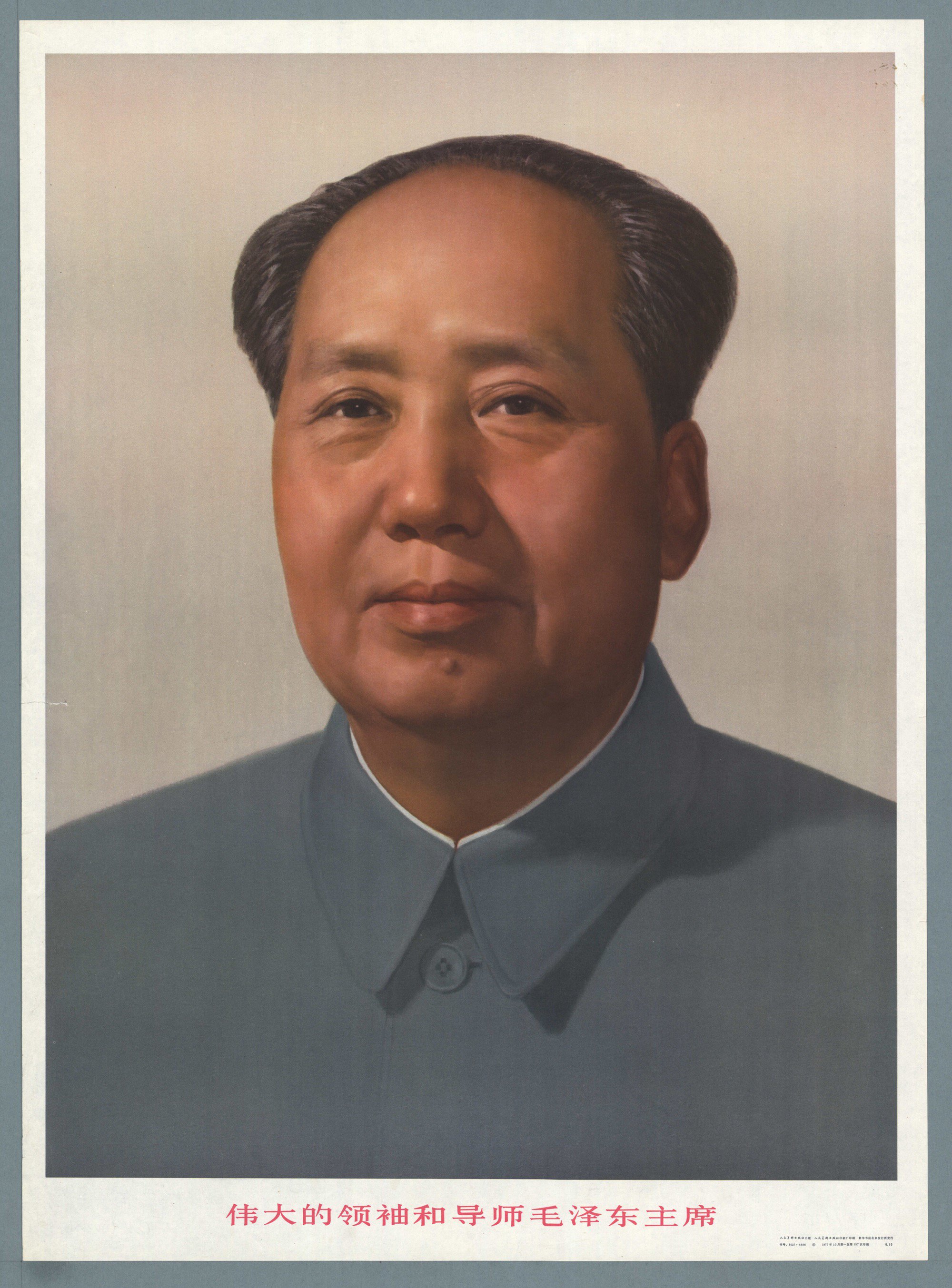

Portraits of Mao Zedong 毛泽东 had been used prominently for propaganda purposes at least since 1935, when he accepted the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).1 The Mao portrait looking out on Tian’anmen Square in Beijing, measuring 6.4 by 5 meters and weighing 1.5 tons, is probably the most famous and enduring. It took the place of a portrait of Sun Yatsen 孙逸仙, the first president of the Republic of China, the 'father of the nation', that appeared above the central gate in 1929. After recapturing Beiping at the end of the Sino-Japanese War in 1945, the portrait of Chiang Kai-shek 蒋介石, the President of the Republic of China, replaced it.2 It stood on the balcony, almost reaching the roof of the gate-building. Mao’s first portrait on Tian’anmen made its debut on 12 February 1949; designed by Dong Xiwen 董希文 and others, it was replaced by a second portrait by the same designer team in July 1949. Eight months later, when Mao proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic, the third portrait was put up, based on a photograph taken in Yan’an and turned into a painting by Zhou Lingzhao 周令钊. By May 1950, it was replaced by a portrait by Xin Mang 辛莽, who also created a version that would hang from 1 October 1950 until 1 May 1952. Zhang Zhenshi 张振仕 painted the next version, making its first appearance on 1 October 1952 and remaining until 1963. In the period 1964-1967, it was Wang Guodong’s 王国栋 portrait that looked out over the Square [See ⧉source: The great leader and teacher Chairman Mao Zedong, also depicted to the left]. Wang Guodong and his student, Ge Xiaoguang 葛小光, would continue to paint the version that has been used from 1967 until the present. All these versions show different Mao’s: the first portrait is frontal (showing ‘two-ears’); the second shows Mao from the left (‘one-ear’); the third also from the left; the fourth from the right (‘one-ear’); the fifth from the left; the sixth full-frontal (‘two-ears’); the seventh from the left; and the final portrait is full-frontal again.3 These different versions and postures indicate that there initially was some uncertainty about how to best present the Leader to the people and the world, but settled in the end on '… an idealised benign face done in a near photographic manner, taking advantage of the play of light and shadow over the Chairman’s features. It is not a lively portrait; rather, a kind of serenity seems to dwell on the face of the man, gazing into nowhere, almost disinterested in human affairs. On his lips is the shadow of a smile. He is dressed in a bluish grey uniform-like tunic originally introduced as official wear by Sun Yatsen in the early days of the Republic. The background is a celestial blue.'4

Images of Mao

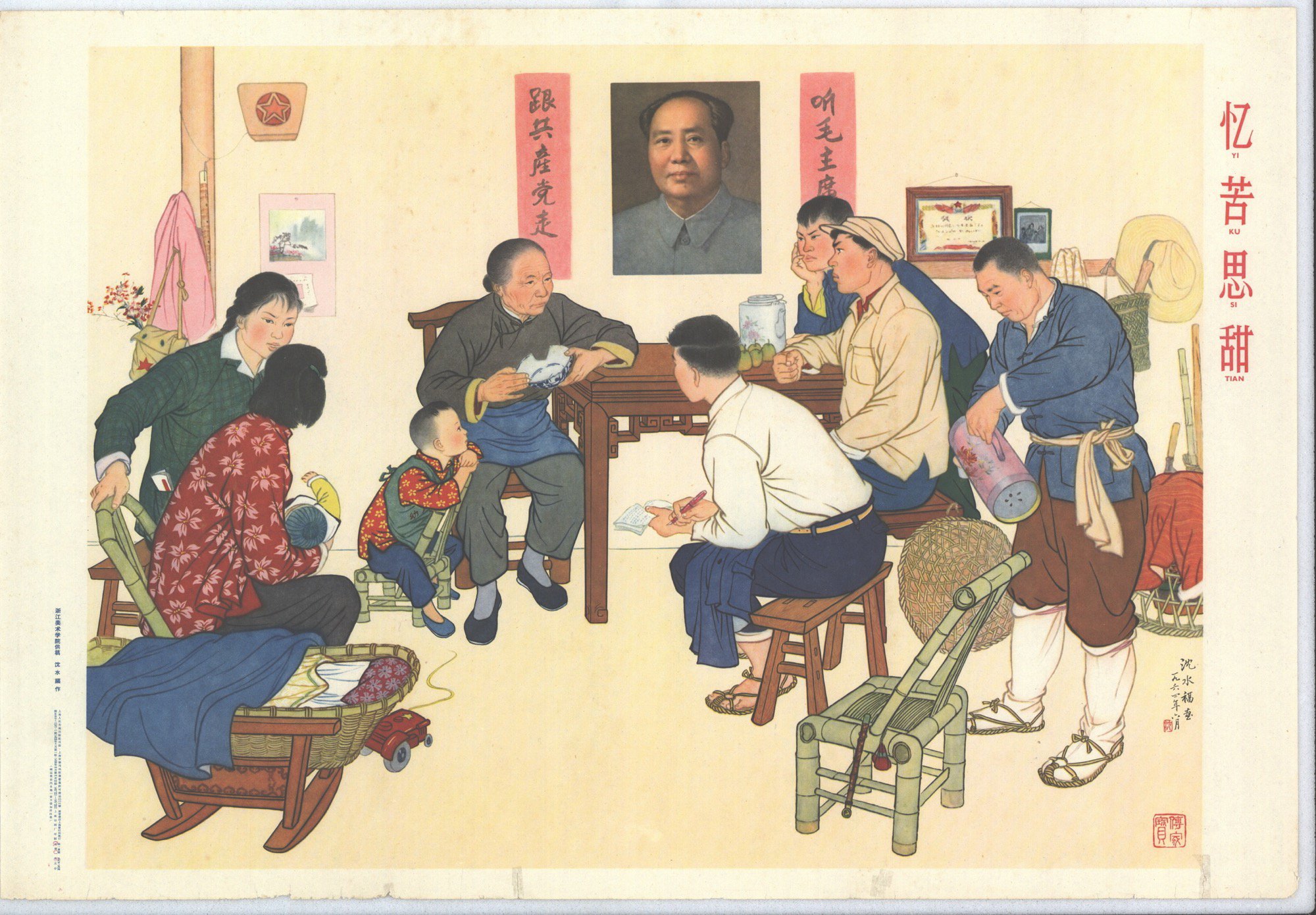

Aside from this official portrait, Mao’s face graced millions if not billions of propaganda posters, produced for different audiences, venues, policies, occasions, campaigns and events. As a leader cult developed in the 1950s and 1960s, despite Mao’s ambiguous warnings against leader worship, his image started to dominate all aspects of daily life. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s image simply was everywhere [See ⧉source: Resolutely support the communique of the Eleventh Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress]. With politics taking precedence, Chairman Mao Zedong, as the Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Helmsman, and the Supreme Commander, became the only permissible subject. No matter how he was visualized, he had to be painted red, bright, and shining (hong, guang, liang 红, 光, 亮); no grey was allowed for shading, and the use of black was interpreted as an indication of an artist’s counter-revolutionary intentions.5 The attention to the use of specific colours found its origin in traditional ideas about the symbolic effects they had; it still plays a role of paramount importance in the painted faces in Chinese opera.6 His face was painted in such a way that it appeared smooth and seemed to radiate as the primary source of light. Often, Mao’s head seemed surrounded by a halo, which emanated a divine light illuminating the faces of the people standing in his presence, a practice that followed the Buddhist tradition.7 He was depicted as a tall, robust person, standing out as a leader; by showing his girth and his long earlobes, his destiny of greatness and good fortune were apparent to everyone.8 In the few posters where Mao did not feature prominently, his symbolic presence was hinted at by the use of symbols like the ‘Little Red Book’, or his selected works [See ⧉source: The red flower of Dazhai blossoms everywhere]. The Mao portrait embodied CCP rule and entered the private spaces of the people. Where he originally looked down benignly on the new affluence and security that the revolution had created for workers and peasants, his presence in the home increasingly came to serve as an expression of the revolutionary commitment of the household members [See ⧉source: Expressing revolutionary commitment, including the image depicted to the right]. Not having Mao on display raised questions about political trustworthiness and ideological awareness.

Anyuan

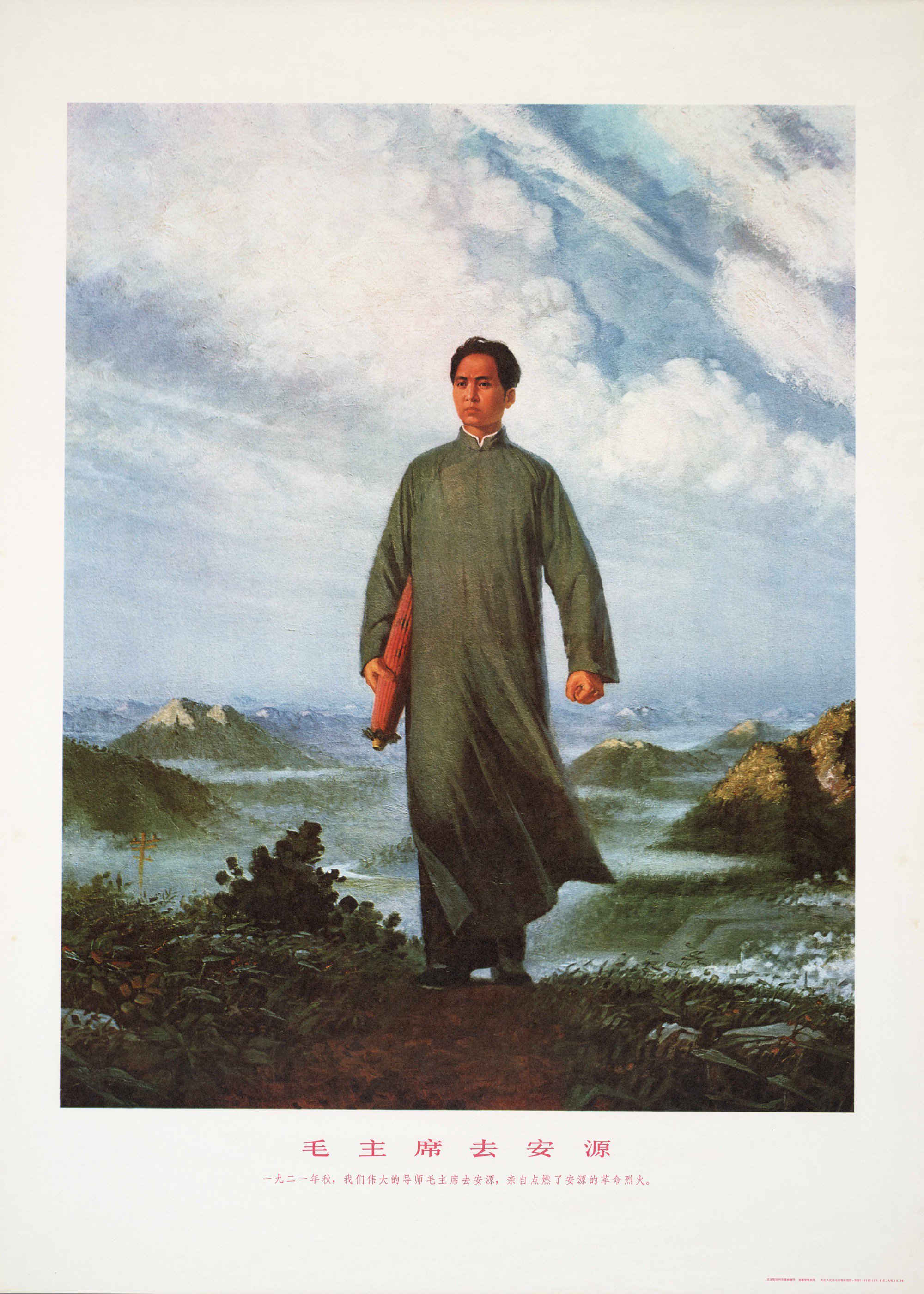

With such weight attached to the impression he cast about, every detail of Mao’s representations had to be preconceived along ideological lines and invested with symbolic meaning. The artist Liu Chunhua 刘春华, a Red Guard who studied at the Central Academy of Industrial Arts, painted the famous painting-turned-poster Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan (Mao zhuxi qu Anyuan 毛主席去安源) on the basis of a collective design by a group of students of universities and institutes in Beijing [See ⧉source: Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan, also depicted to the left]. In almost identical ‘interviews’ with him that were published in the English language periodical Chinese Literature and China Reconstructs, aimed at foreign audiences, Liu allegedly explained the creative processes that had guided their work:

'To put him in a focal position, we placed Chairman Mao in the forefront of the painting, advancing towards us like a rising sun bringing hope to the people. Every line of the Chairman’s figure embodies the great thought of Mao Zedong and in portraying his journey we strove to give significance to every small detail. His head held high in the act of surveying the scene before him conveys his revolutionary spirit, dauntless before danger and violence and courageous in struggle and in ‘daring to win’; his clenched fist depicts his revolutionary will, scorning all sacrifice, his determination to surmount every difficulty to emancipate China and mankind and it shows his confidence in victory. The old umbrella under his right arm demonstrates his hard-working style of travelling, in all weather over great distances, across the mountains and rivers, for the revolutionary cause ... The hair grown long in a very busy life is blown by the autumn wind. His long plain gown, fluttering in the wind, is a harbinger of the approaching revolutionary storm ... With the arrival of our great leader, blue skies appear over Anyuan. The hills, sky, trees and clouds are the means used artistically to evoke a grand image of the red sun in our hearts. Riotous clouds are drifting swiftly past. They indicate that Chairman Mao is arriving in Anyuan at a critical point of sharp class struggle and show, in contrast how tranquil, confident and firm Chairman Mao is at that moment [...].'9

‘Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan’ became '[...]perhaps the most important painting of the Cultural Revolution period'.10 It is believed that more than 900 million copies of the painting were eventually printed; it was displayed at meetings and carried around during demonstrations, mass meetings and processions, and many found their way onto walls, next to Mao’s official portrait [See ⧉source: Pledging allegiance to Mao].11 The poster illustrated the formative and tempering processes Mao had gone through, his development from the young revolutionary to the founder of the state to the ultimate Leader of the Cultural Revolution, turning him into something of a Red Guard avant la lettre. The importance of this painting and its message is shown by fact that it was meticulously reproduced on a number of posters, thus spreading its message even further. It is doubtful whether the various layers of deep meaning that Liu Chunhua alluded to were identified by the majority of the buyers of the poster; they simply may have liked its romantic flavor.

Divorced from the masses?

With all these rules governing Mao’s depiction, the more god-like and divorced from the masses he came to be portrayed, often hovering above those masses [See ⧉source: Advance victoriously while following Chairman Mao's revolutionary line in literature and the arts].12 And yet, despite this apparent distance between Leader and Led, there was something in the images that continued to strike a chord with the people, something that invited identification, something recognisable. The ‘imaged’ Mao, while revered, somehow remained separate yet at the same time united with the people, who took pleasure in his presence.13 This was depicted in the many posters showing Mao at work: inspecting fields, shaking hands with the peasants, sitting down with them, and sharing a cigarette; inspecting factories or infra-structural works, joking with the workers, and possibly sharing a cigarette; dressing up in military uniform, discussing strategy with military leaders, inspecting the rank-and-file, or mingling with contingents of Red Guards; or standing on the bow of a ship, dressed in a terry cloth bathrobe after an invigorating swim in the Yangzi River.

After Mao

After Mao’s death and with the ending of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the succeeding leaders tried to do away with the veneration for the single leader that had so marked the preceding decade. Yet the portrait overlooking Tian’anmen Square was not taken down. Soon enough, the new leadership realized that while collective decision making might make sense, doing away with Mao was impossible, if only because it would tarnish the legitimacy of the CCP. In 1993, during the time of the ‘Mao fever’ that marked the centenary of this birth, official posters devoted to Mao were published again. Over the years, the use of propaganda posters has withered; television and online propaganda have become the media of choice. With Mao’s likeness gracing Chinese money since 1999, 'Grandpa Mao', as he is affectionately called, now has become a much sought-after commodity. But aside from enabling Chinese to consume to their hearts’ desire, Mao continues to mobilize them for a variety of reasons. The Mao portrait –as well as the occasional Mao impersonator– plays a prominent role during contemporary mass events, ranging from international football meets; the patriotic anti-Japanese demonstrations that took place in 2012; and smaller, more localized demonstrations where the rights of the people are at stake.14 In rural areas, the Mao image has remained and still is very much present in people’s homes.15

Footnotes

Barbara Mittler, 'Popular Propaganda? Art and Culture in Revolutionary China', Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society vol. 152, no. 4 (2008): 13.

Daniel Leese, Mao Cult – Rhetoric and Ritual in China’s Cultural Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing – Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 68-84; Chen Lu, 'Replaced eight times: the ‘secret’ of Mao Zedong’s portrait on Tian’anmen' (Baci geng xuan, Tian’anmen shang Mao Zedong huaxiangde ‘mimi' 八次更选:天安门上毛泽东画像的“秘密“), 28 September 2016 Xin Jing Bao (http://www.bjnews.com.cn/graphic/2016/09/28/418458.html, accessed 2 October 2016).

Göran Aijmer, 'Political Ritual: Aspects of the Mao Cult During the Cultural "Revolution"', China Information Special issue: Perspectives on Mao and the Cultural Revolution vol. 11, no. 2/3 (1996): 221.

Jerome Silbergeld, Contradictions: Artistic Life, the Socialist State and the Chinese Painter Li Huasheng (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993), 43; Joan Lebold Cohen, The New Chinese Painting 1949–1986 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987), 22; Julia F. Andrews, Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China 1949–1979 (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1994), 360.

C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism & Art Motives (New York: Dover Publications, 1976 [1941]).

Andrews, Painters and Politics, 360.

Mayfair Mei-hui Yang, Gifts, Favors & Banquets—The Art of Social Relationships in China (Ithaca.: Cornell University Press, 1994), 250.

Liu Chunhua, 'Singing the Praises of Our Great Leader is Our Greatest Happiness', Chinese Literature (September 1968): 32-40; Liu Chunhua, 'Painting Pictures of Chairman Mao is our Greatest Happiness', China Reconstructs (October 1968): 2-6. See also Zheng Shengtian, 'Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan – A Conversation with the Artist Liu Chunhua' in Art and China’s Revolution, edited by Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian (New York: Asia Society/Yale University Press, 2009), 119-131.

Ellen Johnston Laing, The Winking Owl—Art in the People’s Republic of China (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1988), 67-70.

Andrews, Painters and Politics, 339.

Johnston Laing, The Winking Owl, 66-67.

Geremie Barmé, Shades of Mao—The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1996), 19.

Timothy Cheek, 'The Multiple Maos of Contemporary China', Harvard Asia Quarterly (2008): 17, 18-19. See also Ou Ning, Meishi Street [Film] (dGenerate Films, 2006).

Analysis of countless photographs and personal observations, February 1980-May 2019.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: The 3 July And 24 July Proclamations Are Chairman Mao's Great Strategic Plans!

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: The Great Leader And Teacher Chairman Mao Zedong

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: Resolutely Support The Communique Of The Eleventh Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress, Warmly Welcome A New Great Victory Of Mao Zedong Thought

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: The Red Flower Of Dazhai Blossoms Everywhere

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: Expressing Revolutionary Commitment

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: Chairman Mao Goes To Anyuan

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: Pledging Allegiance

- ⧉Image Mao Posters: Advance Victoriously While Following Chairman Mao's Revolutionary Line In Literature And The Arts

Geography

Timeline

Further Reading

Andrews, Julia F. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China 1949-1979. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Bajon, Jean-Yves. Les années Mao – Une Histoire de la Chine en affiches (1949-1979). Paris: Les Éditions du Pacifique, 2001.

Chiu, Melissa and Zheng Shengtian (eds.). Art and China’s Revolution. New York: Yale University Press, 2009.

Cushing, Lincoln and Ann Tompkins. Chinese Posters – Art from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution San Francisco: Chronicle Books LLC, 2007.

Evans, Harriet and Stephanie Hemelryk Donald (eds.) Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China – Posters of the Cultural Revolution. Lanham, etc.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999.

Galikowski, Maria. Art and Politics in China 1949-1984. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press of Hong Kong, 1998.

Johnston Laing, Ellen. The Winking Owl – Art in the People’s Republic of China. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1988.

Landsberger, Stefan. Chinese Propaganda Posters – From Revolution to Reform. Amsterdam: Pepin Press, 1995.

Leese, Daniel. Mao Cult – Rhetoric and Ritual in China’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge, etc.: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Minick, Scott and Jiao Ping. Chinese Graphic Design in the Twentieth Century. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1990.

Mittler, Barbara. A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Wang Mingxian and Yan Shanchun. The Art History of the People’s Republic of China – 1966-1976 (Xin Zhongguo meishu tushi – 1966-1976 新中国美术图史-1966-1976). Beijing: Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe, 2000.