Toby Lincoln, University of Leicester

Summary

Architecture often has a political meaning. Think of Buckingham Palace, the White House, the Kremlin, or the local government offices such as city hall or town councils. Public spaces in cities such as parks and squares also have political meanings. This biography examines the Great Hall of the People, one of the most important political buildings in China. It describes how the building was planned and constructed during the Great Leap Forward, discusses how the architectural style and the interior symbolized the power, ideology and policies of the Chinese Communist Party, and describes some of what goes on inside.The Importance of Tiananmen Square

The Great Hall of the People was built in 1959 so that the National People’s Congress (NPC) had somewhere to meet. The NPC, which is composed of nearly three thousand members, is the largest parliament in the world, and it almost always passes the laws of the Communist Government without amendment. It is located next to Tiananmen Square, itself an important place in China. One of the reasons that Tiananmen is such an important symbol of the power of the Chinese Communist Party is that it was where Mao Zedong announced the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

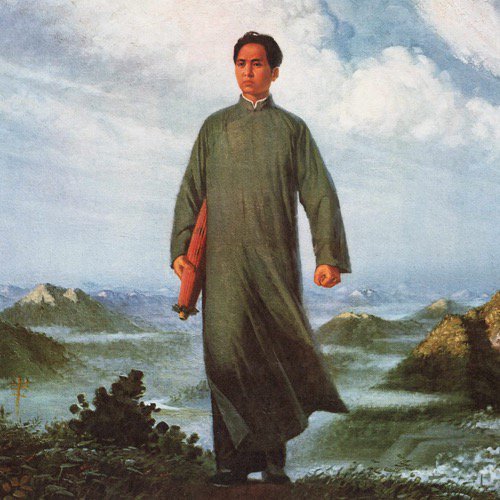

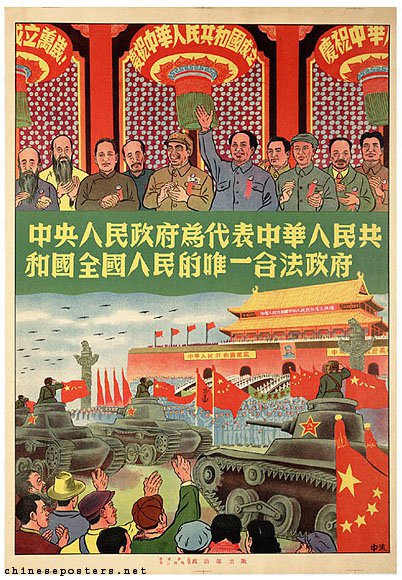

This source is a propaganda poster published in 1950 [see ⧉source: Poster of the parade for the founding of the People’s Republic of China, also depicted to the left]. It shows the parade at Tiananmen to celebrate the founding of the country on 1 October 1949. There are several important leaders of the Chinese Communist Party on the balcony overlooking a military parade, with crowds cheering wildly. Mao Zedong is the one in the centre waving his arm. Parades like this still take place in the square on 1 October every year to celebrate the creation of the country and on 1 May to celebrate Labour Day. Among the groups taking part in the parade in 1949 were the military who displayed equipment such as armoured vehicles, tanks, and missiles, and the young pioneers, who were school students who had joined the Chinese Communist Party.1

Building the Great Hall of the People

The Great Hall of the People was one of ten buildings constructed in Beijing to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The other buildings included the Museum of Chinese History and Revolution, the Beijing Workers Stadium, the Beijing Railway Station, and the Overseas Chinese Hotel. In November 1958, Mao ordered that it be enlarged until it was the biggest such square in the world, and after one million workers had toiled for ten months, it was completed in August 1959. The square was now so large that it could hold up to half a million people.2 The Communist Party held a competition to design the Great Hall of the People, and architects from across the country submitted 84 different designs. Three were chosen to be submitted to the government for approval in October 1958, and they were reviewed by premier Zhou Enlai, who chose the plan submitted by the Beijing Planning Administration. Competition guidelines stipulated that the main hall should be able to hold ten thousand people, probably because the Chinese character 万 wan, which means ten thousand, was a favourite of Mao Zedong. The Great Hall of the People and Tiananmen Square were completed in just ten months. Both were celebrated as successes of the Great Leap Forward, a campaign to quickly develop China’s economy that included the rapid expansion of cities.3 The transformation of Beijing was part of a much larger project to create socialist cities in China, and during the Great Leap Forward many large urban building projects were completed. Across the country, city walls were destroyed to make way for new roads, factories were constructed to produce steel, chemicals, machinery, and other products needed for economic development, and housing districts were built with shops, schools, medical facilities, and sports centres.

To commemorate the construction of the ten buildings in Beijing, a special issue of Architectural Journal (Jianzhu xuebao 建筑学报) was published, and like the buildings themselves this also celebrated ten years of Communist rule [see ⧉source: Front cover of Architectural Journal]. Architectural Journal was published by the China Architectural Society, which was founded in 1953, and represents Chinese architects across the country. It now has ten thousand members, links with many international organizations, holds conferences, publishes books and journals, and organizes architectural competitions.4 The front cover of the journal pictured in this source is red, a colour that is both lucky in China and is the colour of the Chinese Communist Party, and it features a plan of Tiananmen Square. This plan shows the Great Hall of the People on the left and the National Museum of China on the right. In the centre of the square is the Monument to People’s Heroes, which commemorates all those who died during the Communist Revolution. Above is the entrance to the Forbidden City, for many years the home of the emperors in Imperial China. Below is Qianmen, one of the many old gates of Beijing. Its completion, together with the buildings around it, was a signal to the rest of China and the world at large that the Communist Party was now firmly in charge.

The Great Hall of the People

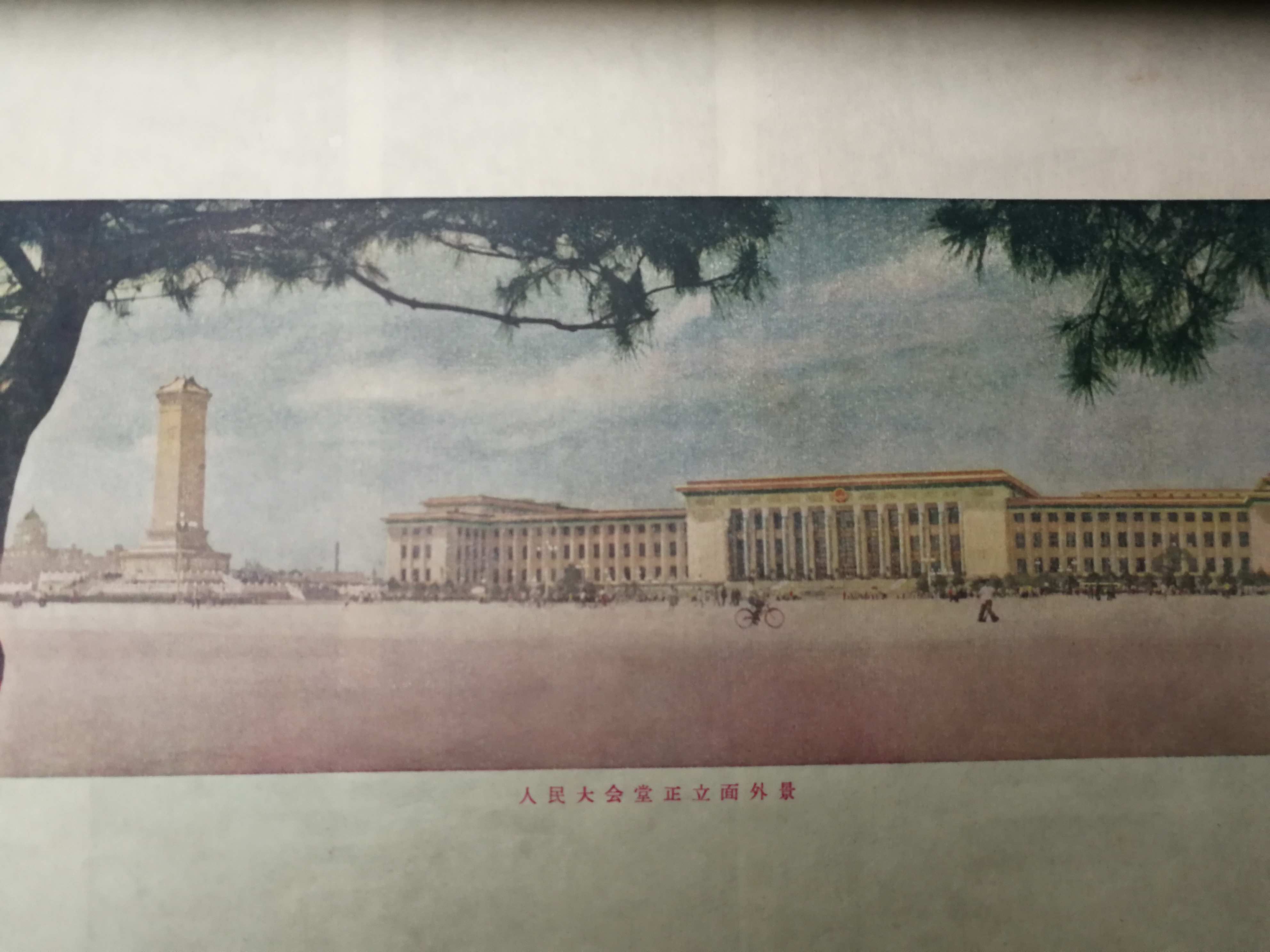

This source [see ⧉source: Exterior of the main facade, also depicted to the right] shows how The Great Hall of the People is an imposing building. It towers above the people in the square, and it is even higher than the Monument to People’s Heroes, which is also pictured. At over three hundred meters long, it is certainly a large building, and the white marble columns support an ornate red roof. The roof is known as a 'big hat roof' (dawuding 大屋顶), and these first appeared in China in the first half of the twentieth century. They look like the roof on a Chinese temple, and Western architects felt that putting them on a modern building preserved Chinese architectural form. In the 1950s, they were sometimes criticized for being extravagant and expensive, but many Chinese politicians and architects felt that they also preserved the long tradition of Chinese architecture. Moreover, advisors from the Soviet Union, who were helping the Chinese to build their cities, also supported the 'big hat roof'.5 The roof is supported by columns that look like those you might see in cities in Europe, and reflects the spread of the European classical style in China. If you look closely, you will see the large windows behind them, which are in the modernist style of architecture that emerged in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. With the mixing of these two styles from Europe in such an important building, it is perhaps not surprising that architects wanted a Chinese style roof.

The Banqueting Hall

Moving inside The Great Hall of the People, this source shows a picture of the banqueting hall in which the circular tables are arranged close together, and there are few columns, which provides a sense of wide open space, even though there are so many people [see ⧉source: Banqueting hall] . This creates a communal feeling, while the circular tables allow for the serving of Chinese food. When several Chinese people eat together, the dishes are placed on a 'Lazy Susan', a circular revolving tray in the centre of the table, and the diners simply help themselves to whatever they feel like.

Main Hall of the Great Hall of the People

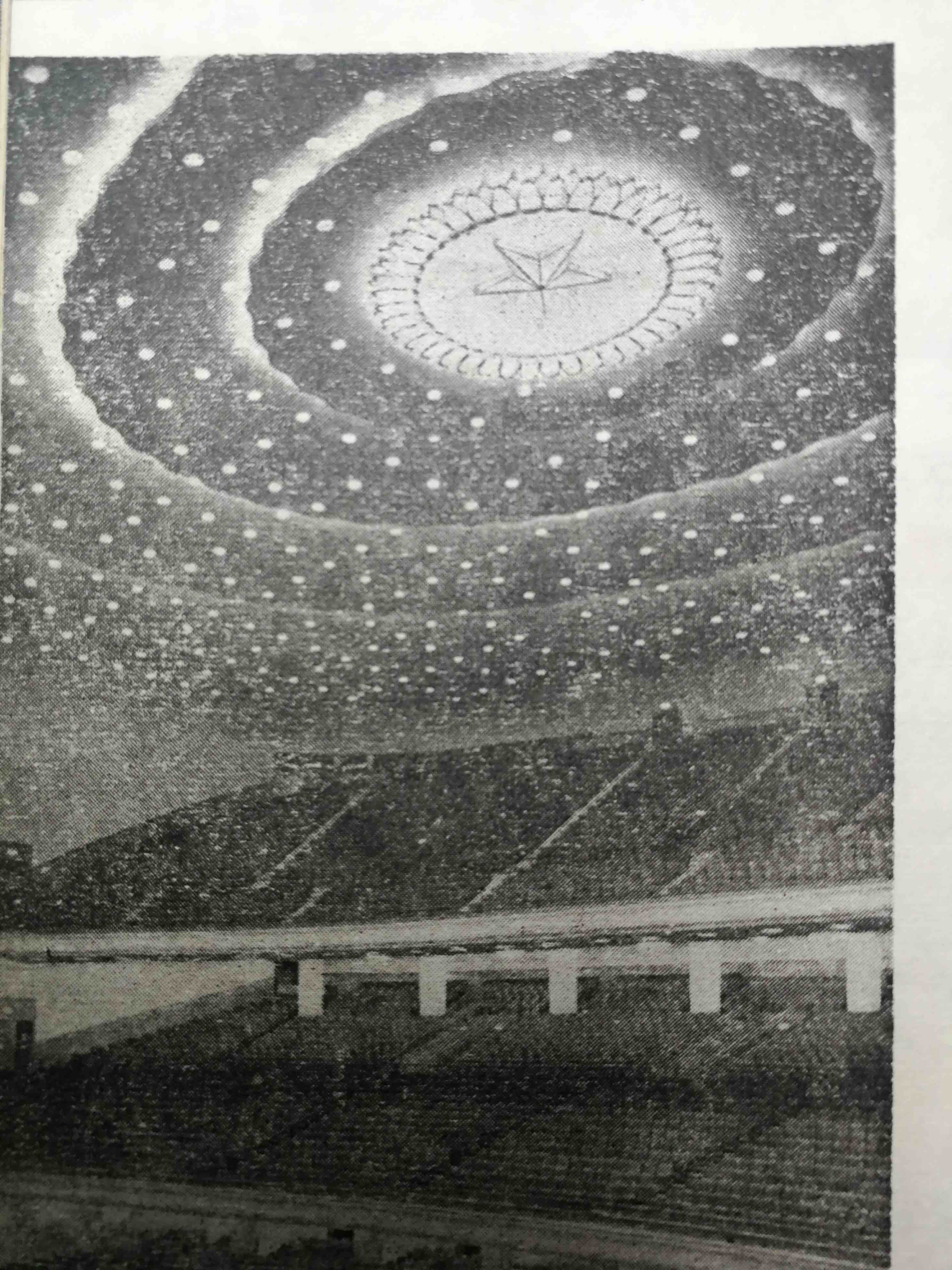

The hall where the National People’s Congress sits looks very much like a theatre [see ⧉source: Large Assembly Hall interior]. It was a technical challenge to sit such a large number of people in one large room so that they could all see the stage, so the architects designed the seats in a semi-circle, and added two large balconies allowing everyone to have a good view of the stage. During the congress, the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party sit on the stage, with the chairman at the centre. This allows them to display their power over the delegates, who must sit through long speeches. The roof of the hall presented a problem, as there were concerns that if it was simply flat, the hall would feel claustrophobic, so two models were built to allow designers to examine the issue in detail. The solution was a large red plexiglass five-pointed star, edged with gold plate [see ⧉source: Suspended star studded sky lights in the main hall, also depicted to the left]. Radiating out from this star three waves of lights provided illumination for the ten thousand people that the room was designed to hold. Other than serving a practical purpose, the waves of lights were supposed to represent the people of China united behind the Communist Party. They in turn, so the design suggested, would be able to rely on the party’s strong and careful guidance to develop the country after the victory it had achieved in the Communist Revolution ten years before.6 Nothing reveals better how a material object can be a technical solution to a practical and in this case an architectural problem, and at the same time a political symbol.

Being in the Great Hall of the People

What was it like to go into the Great Hall of the People? Obviously different people had different experiences depending on several factors, including who they were, and when and why they were visiting. An early visitor was 侯世强 Hou Shiqiang, a 66 year-old former railway worker. His opinions, reported in the newspaper People’s Daily (Renmin Ribao 人民日报), in 1959 soon after the completion of the Great Hall of the People, are particularly interesting, because he had lived on the site where the building was constructed [see ⧉source: A former resident of Qianfu Hutong recalls]:

'I lived in what was Qianfu Hutong in front of Tiananmen, which is now the Great Hall of the People. My family lived there from 1900. That was in a house with 12 rooms that was over 100 years old. The house didn’t look small, and from the outside looked as though it were made of bricks. But the inside was made of broken bricks stuck together with mud. In the past most of the houses that people in Beijing lived in were like this. Every time it rained, we were afraid the house would collapse. We lived like this for sixty years. Now that house has been demolished, and I live in a new building, and in a short time, the country has constructed the Great Hall of the People on the place where I used to live. This is really of great benefit for the country, and for me. Shortly after I had moved house, the Great Hall of the People was finished. On 6 October, we were given a visitor’s ticket to take those of us who had lived there to see it. On the day we went for a visit, they told us that it would be best not to bring children because there were many people on that day, and they were afraid that little children would run and jump about. But everyone took their whole family along. So, adults, children, old ladies.....enthusiastically, Ah, it’s not necessary to say. From when we entered at one in the afternoon until we left at six in the evening, everyone lingered long in each place, looking and commenting, but we were not tired in the slightest. Everyone said this is the auditorium for the all the people in the country. It is our big family … How would this Great Hall of the People be possible without the Great Leap Forward?'7

In this account, the past life of Hou in his ramshackle house, which he was happy to leave, that leaks when it rains is set against the modern building that is the Great Hall of the People. The article shows that he and the other visitors were impressed with the new building, and recognized their connection to it, and the country as whole, as well as the achievements of the Great Leap forward. The article in the main newspaper of China, shows us how the Communist Party wanted the Chinese people to think about what the Great Hall of the People meant. However, we must not dismiss Hou’s point of view. Many if his sentiments may have been genuine. People feel pride in important buildings, and his new house was probably better in many ways than his old one.

A different point of view comes from a congresswoman writing in the 1980s: 'The first thing I noticed when I sat down in the Great Hall of the People was how hard the seats were. They were not nearly as soft as I’d imagined. Honestly, I’m not joking, that really was my first reaction. The next thing I realized was that there was no portrait of Chairman Mao above the rostrum. Before then I’d never given a moment’s thought to the inside of the Great Hall. Why on earth should I? But I’d always had this impression that there was a portrait of Chairman Mao front and center. Later, I learned that it had been replaced by the national emblem after the first session of the National People’s Congress.'8

The Great Hall of the People is not as accessible to the public as some parliaments in other countries. The congresswoman recalls: 'moreover, ordinary citizens don’t have the right to sit in and observe the proceedings. Special seats are set aside for official purposes, but they’re not open to the public. Whatever the reasons for this, I don’t think it’s a good thing.'9

The congresswoman’s account shows how the Great Hall of the People continues to be an important political building in China, because it is where the National People’s Congress passes the country’s laws.

Footnotes

'1 October, National Day of the People’s Republic of China', Source Introduction Page on chineseposters.net (https://chineseposters.net/themes/1-october.php).

Lillian Li, Beijing from Imperial Capital to Olympic City (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 177-179.

Wang Jun, Beijing Record A Physical and Political History of Planning Modern Beijing (Singapore: World Scientific, 2011), 372, 377.

Architectural Society of China (http://www.chinaasc.org/news/16.html).

Wang, Beijing Record, 178-180.

Beijing City Planning Management Department Design Office Great Hall of the People Design Group (Beijingshi guihua guanliju shejiyuan renmin dahuitang sheji zu 北京市规划管理局设计院人民大会堂设计组), 'Great Hall of the People' (Renmin dahuitang 人民大会堂), Journal of Architectural Studies (Jianzhu xuebao 建筑学报), September – October 1959: 29.

Unknown, 'Low buildings turn into tall buildings, a paradise built on earth' (Aifang bian dasha renjian jian tiantang 矮房变大厦 人间建天堂) in People’s Daily (Renmin Ribao 人民日报), 1 November 1959.

'The People's Diary A congresswoman' in China Candid: The People on the People’s Republic, edited by Ye Sang, Geremie Marmé, and Miriam Lang (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 73.

Ibid., 81-2.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: The Parade For The Founding Of The People’s Republic Of China

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: Celebrating The Tenth Anniversary Of The Founding Of The Country In Journal of Architectural Studies

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: Exterior Of Main Façade

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: Repair Of The Interior Of The Banqueting Hall

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: Large Assembly Hall Interior

- ⧉Image Great Hall Of The People: Suspended Star Studded Sky In The Main Hall

- 文Text Great Hall Of The People: A Former Resident Of Qianfu Hutong Recalls

Geography

Beijing’s Tian’anmen Square and Tian’anmen rostrum are two of the most important icons in Communist China. The rostrum is frequently depicted on badges [see Mao Badges: Source Revolutionary heritage badge, 9th Congress Mao badge, Mao Zedong and Lin Biao badge].

Tiananmen Square is a large square in the centre of Beijing, named after Tiananmen, a gate to the north of the square, which separates it from the Forbidden City. It contains many important buildings in China, and has been the site of important political events. These include the May Fourth protests in 1919 and the June 4th protests in 1989.

Timeline

Further Reading

Friedman, John. China’s Urban Transition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesotta Press, 2005.

Li, Lillian. Beijing: from Imperial Capital to Olympic City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Lu, Duanfang . Remaking Chinese Urban Form Modernity, Scarcity and Space, 1949-2005. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006.

Sit, Victor. The Nature and Planning of a Chinese Capital City. New York: J. Wiley, 1995.

Wang, Jun. Beijing Record A Physical and Political History of Planning Modern Beijing. Singapore: World Scientific, 2011.

Wu, Hung. Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space. London: Reaktion Books, 2005.