Covell Meyskens, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School

Summary

Radio was a major way for the Chinese Communist Party to transmit the voice of the central government into family homes and workplaces situated all throughout the country. Villages, schools, industrial enterprises, and government organizations were all outfitted with PA systems, and local radio operators tuned in every day to relay broadcasts from the Central People’s Radio in Beijing, so that everyone was kept on the same ideological wavelength about how to understand the latest political, economic, social, and cultural changes occurring in Mao’s China. In practice, listening to the radio took on a variety of different meanings in people’s everyday lives.Radio Comes to China

When radio came to China at the start of the twentieth century, the Chinese government conceived of wireless communication as a way to increase the reach of the state. Of particular interest was using radio for military purposes. This securitized view led the government to forbid public purchasing of wireless equipment, a ban which was only partially effective since it did not apply to the foreign concessions controlled by imperial powers in Chinese cities. Most notable of all was the international concession in Shanghai where by the 1920s entrepreneurs had begun to create a local radio culture with big stars and brand advertising. Warlords also flaunted government regulations and set up radio stations in areas under their authority.

Upon taking power in 1927, the Nationalist Party ended the restriction on public acquisition of radio equipment. Despite this loosening up, Nationalist officials still primarily thought of radio as a means of cultivating popular adherence to government objectives. Radio was deemed particularly relevant to accomplishing this goal because the majority of Chinese were illiterate. Elaborate plans were drawn up to construct a nationwide network of radio stations centered on the capital at Nanjing which would disseminate Party-approved content to the far corners of the county.

This nation-building dream was never realized due to political instability and reliance on imported equipment from the United States, Germany, and especially Japan, which the Nationalist Party ironically despised for broadcasting pro-Japanese content in China that undermined Nationalist political authority. In the end, the Nationalist regime was only able to extend its radio message to provinces around Nanjing in the 1930s and to provinces in the Southwest after the Japanese forced an inland retreat during World War II. In both cases, the Nationalists strived to instill in the Chinese people an appreciation of proper moral conduct and healthy living and a belief in the centrality of the Party to national affairs.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), in contrast, only set up a radio station at its revolutionary base area in Yan’an in 1944 thanks to equipment furnished by the Soviet Union. Although it was only at this late date that the CCP gained the capacity to make its voice heard over the airwaves, radio had already played a pivotal role in its history. At the CCP’s first major base area in Jiangxi province, the leadership had been in regular radio communication with Moscow which had favored Chinese cadres trained in the Soviet Union over Mao Zedong and other local leaders. During the Long March, radio contact with Moscow lapsed due to faulty vacuum tubes, a technological difficulty which facilitated Mao’s rise. Once Yan’an acquired a radio station, it broadcast propaganda to mobilize the local population, a strategy which the People’s Liberation Army also deployed when it conquered southern China during the Civil War.

Building a Socialist Radio Culture

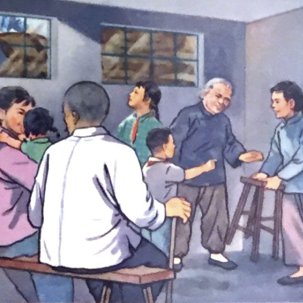

When the CCP came to power in 1949, it implicitly embraced the Nationalist Party’s objective of projecting government power through a centrally directed radio system. The core of this initiative was Central People’s Radio in Beijing which transmitted content to newly established provincial and municipal stations. The majority of people did not live in big cities, and so in 1955, the government launched a drive to expand radio infrastructure in the countryside. Short on equipment, enlargement efforts did not focus on founding local radio stations. They concentrated on furnishing rural areas with equipment to relay signals from central, provincial, and municipal stations and rebroadcast them over a local loudspeaker system. By 1964, this infrastructure-building project had yielded radio stations in every county, and loudspeakers in roughly ninety-five percent of villages, which were installed on government buildings, local homes or on a tall pole in a heavily frequented public place. Similar practices were employed in urban areas where schools, factories, and government offices were all equipped with PA systems [see ⧉source: Listening to the radio in 1956, also depicted to the left].

Making possible this entire endeavor was a concomitant push to increase China’s stock of radio equipment. Initially, the CCP relied on factories built by the Nationalists, Japanese, and the local business community. Their output capacity was insufficient to realize Beijing’s aspiration of being able to wirelessly communicate with every person in China. To make up for this shortfall, Party leaders appealed to the Soviet Union to assist with enhancing local production capabilities. Manufacturing at first centered on vacuum tube radios made principally from parts imported from Eastern Europe and China’s socialist big brother. In the late 1950s, the Sino-Soviet alliance felt apart partially over disagreements about radio’s place in their partnership with Moscow proposing a radio station in China to monitor the Soviet Pacific fleet and Beijing rejecting this idea as an encroachment on Chinese sovereignty. Fortunately for the Communist Party, China had already established a wireless industry that could supply vacuum tube radios as well as move production into transistor radios in the mid-1960s.

Between 1949 and 1952, most radio programming was geared towards consolidating the Party’s control. This was done from the regime’s very first day in existence. When Chairman Mao ascended the rostrum at Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949 and declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China, his speech went out live on the radio. Microphones were also placed around the square to capture audience enthusiasm and the accompanying military parade. In the early fifties, the CCP continued to affirm its connection with the Chinese people through live broadcasts of mass rallies for big political initiatives, such as the Campaign against Counterrevolutionaries, which publicly delineated who counted as China’s friends and enemies both at home and abroad. To firm up China’s international standing, the CCP also began radio transmissions in 1950 to overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia in Mandarin and local languages.

During the First Five Year Plan (1953-1957), radio content shifted and laid more emphasis on the importance of hard work, raising economic output, and building socialism in China [see ⧉source: Construction workers tune in to the radio in 1954, also depicted to the right]. More cultural programs were also diffused over the airwaves. Some such programs consisted of traditional Chinese cultural forms, such as xiangsheng (相声) in which two men engaged in witty banter, while other programs were comprised of stories of the CCP’s heroic actions fighting the Nationalists, Japanese, and other enemies of Chinese socialism. Music became a regular feature of programming too, as did newscasts which chronicled recent activities of Party leaders, celebrated economic accomplishments, and described the machinations of the United States and its allies to impose their imperial designs and capitalist inequality on China and the rest of the world. Sino-Soviet friendship, on the other hand, was attested to by the Party’s decision to every night devote a half hour of primetime to Chinese translations of news digests out of Moscow.

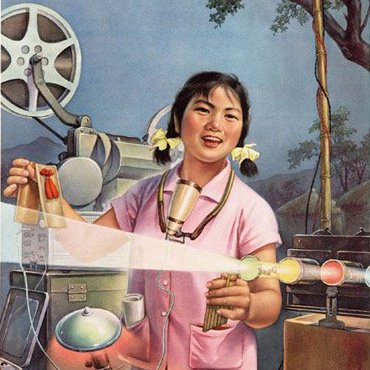

During the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), lighter cultural fare largely disappeared, as radio stations urged local areas to mobilize labor to quickly boost economic production [see ⧉source: 1959 Broadcast station at a water reservoir construction site]. Particular emphasis was placed on the vital role that the military and spartan discipline played in rapidly advancing socialist construction. At the same time, the radio used celebrations of 'socialist achievements' to demonstrate the inclusiveness of the campaign, here by highlighting the role of women [see ⧉source: Women Of China Article]. When the Great Leap failed, and famine spread across the country, radio was silent about the unfolding disaster. When the economy recovered in the early sixties, cultural content regained a prominent position in radio programming. This trend was not to last.

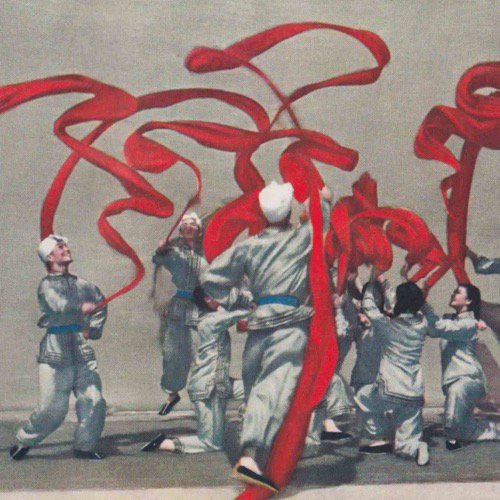

Radio broadcasters again called for the mass mobilization of labor in 1964 when increased American involvement in the Vietnam War and rising tensions with the Soviet Union led Party leaders to accelerate economic development. Readings of Mao’s works also came to be a more frequent feature of radio broadcasts with the publication of the Little Red Book and the deepening of Mao’s cult of personality in the lead up to the Cultural Revolution. During the height of this momentous campaign, Mao quotations were daily piped via loudspeakers into factories, schools, government buildings, and villages, and radio shows were consecrated to teaching how to correctly interpret Mao Zedong thought. Chinese citizens were also obliged to listen to struggle sessions against people accused of betraying Chinese socialism and seeking to push the country onto a capitalist road. Radio stations provided Chinese citizens with means to affirm their loyalty to Chairman Mao and China’s socialist project by playing revolutionary tunes for them to sing along to, while another famous melody caused people to drop everything and start performing the Mao loyalty dance to the state-sanctioned rhythms of the Cultural Revolution.

Radio in Everyday Life

People did the Mao loyalty dance not because of a formal rule but because of their awareness that it was what someone did when they heard the associated song. In other instances, collectively listening to the radio was required. This practice was particularly common during the early fifties, Great Leap, and Cultural Revolution when the central government pushed hard to rally the Chinese people around the achievement of a shared set of political objectives. During group listening sessions, students, villagers, or workers congregated a radio and listened to the latest updates on China’s situation. Afterwards, local leaders guided the group through a discussion of the topics covered, which could be about how to advance a domestic campaign, such as marriage reform, or could be related to China’s Cold War allies and foes.

Even during periods when work-units less frequently held collective listening activities, radio still structured the routines of everyday life. Every morning, people of all walks of life lined up in rows and performed exercises accompanied by music selected by central radio officials to keep citizens physically fit for the collective mission of building socialist China. Everyday life was also punctuated by morning and nightly broadcasts that kept up awareness of how local actions were part and parcel of the broader movement to advance socialism and defeat its adversaries both within China and beyond its borders.

Local radio operators were trained to aid with this socialization process by tuning into special broadcasts designed expressly for them. During these transmissions, central radio personnel would slowly recite the key topics of the day and outline what key words should be used to discuss them. The details were repeated several times, so that the person on the receiving end had enough time to write them down. Local radio workers then took this information and made it the basis of broadcasts at their work-unit. On other occasions, they printed it up in the work-unit newspaper or wrote it up on public blackboards where locals were encouraged to go read the news.

Some of what radio operators heard was standardized across the country, items such as major news events and recent Central Party directives. Other information varied based on a place’s position in the national radio landscape. Certain frequencies targeted urban areas, the countryside, and military personnel, and provincial and county radio stations put out broadcasts tailored to local happenings. One reason for modifying radio content was the broad diversity of Chinese dialects, to say nothing of minority languages, which made it virtually impossible for the Central Radio to generate programming that was comprehensible to everyone in China. Another reason for localizing radio efforts was to promote local examples of the conduct that the Party desired, which might mean provincial authorities extolling a model laborer or a village praising a particular worker’s performance over the PA system.

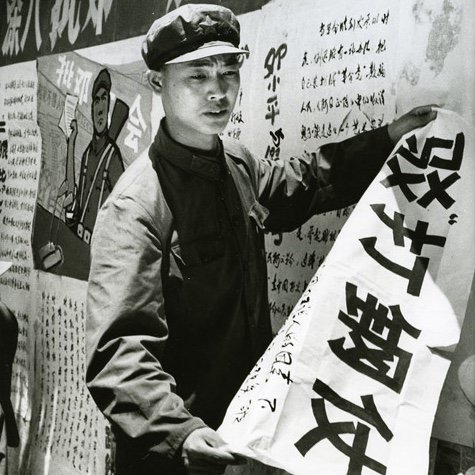

One kind of behavior that school teachers cautioned students against was 'listening to enemy broadcasts (shouting ditai 收听敌台)' from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Voice of America. School children were warned that if they disobeyed this order, then they were not just wronging socialist China, they were committing a crime. This did not just apply to students but also to the military. In 1962, the General Political Department of the People's Liberation Army forbade listening to foreign broadcasts [see ⧉source: People's Liberation Army notification]. At the same time, civilians were also not supposed to eavesdrop on the portion of the radio spectrum assigned to the military. If someone listened in nonetheless, there was little that they could understand since broadcasts typically consisted of strings of numbers that made no sense to someone without the relevant cipher.

The Party-curated character of mass media in Mao’s China might make it seem that listening to the radio only involved the government dictating to people what they were supposed to think and feel. While the CCP definitely considered radio to be a key instrument in its social engineering toolkit, the Chinese people also listened to specific programs because of the information they contained. Some monitored weather forecasts to know whether it would be sunny or rainy later in the week. Others were interested in what newscasts told them about what was going on around the country and the wider world. Keeping abreast of national events was particularly important to workers sent to develop the country’s interior as well as students dispatched during the Sent Down Youth Campaign to work in rural areas far from their hometown. For people in this situation, radio was one of the few ways that they could gain knowledge about events outside of their locale.

For people seeking scholarly edification, radio stations offered a slew of educational programs as part of the CCP’s drive to popularize technical and scientific knowledge, while other listeners tried to make time after work or school to catch their favorite program, whether it was a show for youngsters with stories about the Chinese revolution, a live broadcast of the National Day parade, a special performance by a well-known opera star, or to learn more about major national achievements such as the explosion of China’s first atomic bomb in 1964.

To hear what was on the radio, most urbanites could not do so in the comfort of their own home. They had to visit whichever neighbor had accumulated enough money to purchase one, a situation which led to neighbors debating what programs they should play over the radio. Such discussions typically did not take place in the cash-strapped countryside where the only option was to listen to the local PA system. In cities, personal radio ownership was more common but still marked someone off as being of a higher social status. When the Red Guards ransacked homes searching for evidence of capitalist decadence during the Cultural Revolution, possession of a radio was often taken to be a telltale sign of a politically suspect character. The fact that Red Guards often confiscated radios also likely indicates that some of them coveted their very own radio but could not afford it.

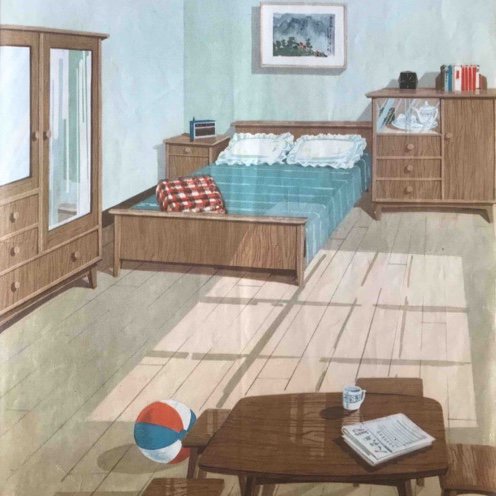

Radios were so popular that they were made into one of the 'Four Big Items' (si da jian 四大件) that a man was expected to provide a prospective wife [see ⧉source: Radio interview]. If a man could not do so, then the woman or her parents might reject his marriage proposal. Fulfilling this matrimonial obligation put considerable financial strain on males. For rural men, this was especially difficult since most were paid in work-points and had very little cash. Even for urban families, obtaining a radio did not come easy. They had to save up several months of wages which often took several years. Some individuals opted instead to search out radio parts at local markets and build their own, a skill taught to urban school children [see ⧉source: Children assembling a radio, also depicted to the left]. Although radios assembled in this manner were not of high quality, their makers often still fondly remember them as symbols of their technical skill and can tell stories of the hours they whiled away with friends, family, and coworkers gathered around the radio.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Radio: Listening To The Radio In 1956

- ⧉Image Radio: Construction Workers Tune In

- ⧉Image Radio: 1959 Broadcast Station At A Water Reservoir Construction Site

- ▤Pdf Radio: Women Of China Article

- ▤Pdf Radio: People's Liberation Army Notification

- 文Text Radio Interview

- ⧉Image Radio: Children Assemble Radio In The Early 1960s

Geography

On 30 December 1940, the CCP establishes the Yan’an Xinhua Radio Station at its revolutionary base area in Shaanxi province, which will later become the Central People’s Broadcasting Station.

In November 1956, the Beijing Institute of Applied Physics successfully test China’s first self-made transistor.

Timeline

Further Reading

De Giorgi, Laura. 'Communication Technology and Mass Propaganda in Republican China: The Nationalist Party’s Radio Broadcasting Policy and Organisation during the Nanjing Decade (1927-1937)'. European Journal of East Asian Studies 13 (2014): 305-329.

Howse, Hugh. 'The Use of Radio in China'. The China Quarterly, No. 2 (June 1960): 59-68.

Jan, George P. 'Radio Propaganda in Chinese Villages'. Asian Survey vol. 7, no. 5 (1967): 305-315.

Shen, Yu 沈榆 and Zhang, Guoxin 张国新. 1949-1979 Chinese Industrial Design Collected Archival Documents (1949-1979 Zhongguo gongye sheji zhencang dang'an 1949-1979中国工业设计珍藏档案). Shanghai: Shanghai Renmeishu chubanshe, 2014.

Shen, Yu 沈榆 and Wei, Shaonong 魏劭农. Made in Shanghai (Shanghai zhizao zhong de sheji 上海制造中的设计). Guilin: Guangxi Shifandaxue chubanshe, 2018.

Xu, Chuan. 'From Sonic Models to Sonic Hooligans: Magnetic Tape and the Unraveling of the Mao-Era Sound Regime, 1958–1983'. East Asian Science, Technology and Society vol. 13, no. 3 (2019): 391-412.