Alfreda Murck, Columbia University/ Metropolitan Museum of Art

Summary

Washbasins were an important utilitarian item in Mao era China. In the absence of indoor plumbing, homes and offices used enamel basins for washing up. Called “face-washing basin” in Chinese (xi lian pen 洗臉盆), washbasins can be thought of as all-purpose sinks. An essential item in every home, in the Mao era washbasins became a vehicle for social and political messaging.Washbasins

Washbasins were an important utilitarian item in China until buildings were equipped with indoor plumbing. Traditionally people fetched water from wells or from nearby spigots and poured the water into a large basin. In the winter, boiling water was added to take off the chill. For a full scrub, most people went to public bathhouses [see ⧉source: Good hygiene]. In addition to hands and faces, washbasins were used to wash everything from feet and vegetables to clothes and babies [see ⧉source: Washbasins in factory nursery]. Washbasins could be carried around to clean windows or to shampoo hair. They also doubled as mixing bowls for making large batches of dumpling filling or noodles. Better-off households were more likely to have separate basins for different tasks. In pre-modern times, inexpensive washbasins were made of ceramic or wood. More expensive ones were made of bronze, sometimes with cloisonné enamel decoration. In the twentieth century, vitreous enamel became the material of choice. This object biography describes how vitreous enamel is produced, the uses of washbasins, and the features that make the 1956 washbasin informative.

How is Vitreous Enamel made?

Vitreous enamel (also called porcelain enamel and industrial enamel) is a metal form to which a glassy surface is fused through heating. A clean metal object is sprayed with a soupy mixture called frit, which is finely ground glass suspended in liquid clay. Coated with frit, the object is fired at temperatures of more than 800 degrees C. During firing, the 1956 washbasin was positioned on a frame that touched the underside of the rim at six points. After cooling, decoration or inscription can be added in different colors, after which it is fired again. Color is created by adding small amounts of metal oxides to the frit. Almost any metal can be enameled, but steel proved to be sturdy and the most reliable in fusing with frit. Enamelware has many advantages. It has a smooth, impervious surface that is easy to clean.1 It is scratch resistant and doesn’t break, although it does chip. The color does not fade because it is glass not paint.2

In 1916 British industry pioneer J. H. McGregor introduced vitreous enamel to Shanghai.3 With long expertise in ceramics and glass-enameling, China quickly adopted the technology. During the Republican era (1911-1949), several factories were built in major cities. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, their number increased.

The July 1956 Washbasin and Inscription

In the 1956 washbasin that is featured here, the young woman pausing over a sketch of an airplane may have been thinking of being a pilot. Like the Soviet Union, China celebrated women who were skilled at aeronautics. Coinciding with campaigns to improve health and hygiene, this washbasin was presented to a military veteran’s dependent who was also active in establishing socialism. The inscription documents the 1950’s movement to promote literacy through simplification of the Chinese written language, while the factory seal pertains to the economic reforms of 1956.

The inscription, which is stenciled in red enamel on the outside of the washbasin, gives a specific date and context [see ⧉source: 1956 Washbasin, interior, exterior, factory seal, Image 2 exterior, also depicted to the left]. It was a gift from Tianjin city government to a special group of citizens who were active in establishing Socialism. The full inscription reads: 'Award Ceremony for Tianjin Dependents of Military Martyrs and Honorably Discharged Veterans [who have been] Activists in Establishing Socialism. Presented by Tianjin Municipal People’s Committee, 15 July 1956' (Tianjinshi lieshu junshu rongfu junren shehui zhuyi jianshe jiji fenzi dahui jiangpin Tianjin shi renmin weiyuanhuizeng 天津市烈属軍屬榮復軍人社会主义建設 积极分子大会奖品. 天津市人民委員会贈). The dependents would have included relatives of veterans of World War II as well as the Korean War (in China is called 'the American War'). At the urging of the Soviet Union, in October 1950, China had sent hundreds of thousands of troops to aid the North Korean regime. Over almost three years of conflict, China suffered an estimated 148,000 fatalities.4 After an armistice was signed on 27 July 1953, many Chinese soldiers returned with honorable discharges. We don’t know what the activists did to earn the award or how many of these special washbasins were presented.

In dynastic China and much of the twentieth century, Chinese characters were written vertically from top to bottom in columns that proceeded from right to left. In 1955 the language reform formalized what many publishers had been doing for decades: printing texts in horizontal lines from left to right.

The washbasin inscription is unusual in being composed of both traditional characters and the newly-issued simplified characters. As part of a national program to promote literacy, a Committee for Reforming the Chinese Written Language was formed in 1953.5 They examined commonly-used Chinese characters and designed versions with fewer strokes. They developed a new Romanization system called Pinyin. Some scholars envisioned eliminating characters all together in favor of a phonetic language written with the western alphabet.6

In 1956, 798 simplified characters were introduced, some each month. On the washbasin the word for 'activist' (jiji 积极) with 17 strokes was originally written with 28 strokes: 積極. The suffix 'ism', as in Socialism, which appears on the washbasin as 主义 (8 strokes), had previously been written 主義 (a total of 18 strokes). At the time of the washbasin’s manufacture, the simplified form for 'establish' 設 (11 strokes) had not yet been issued; it would become 设 (6 strokes).

Enamel Ware as Gifts and Political Propaganda

From the 1950s and into the 1970s, enamel mugs and washbasins were presented as retirement presents, wedding presents, and prizes to model workers and exemplary socialists. They were also used to commemorate significant milestones such as the first detonation of a hydrogen bomb in 1967 or to announce political slogans [see ⧉ source: Hydrogen bomb washbasin]. In 1973 the character 'prize' was boldly printed in a deep washbasin made in Lanzhou for winners in Socialist Labor Competitions at the Lanzhou Enameling Factory [see ⧉source: Lanzhou 'prize', also depicted to the right]. The inscription is entirely in simplified characters, but it includes one simplified character that caused confusion and was withdrawn: in the binome 'competition' (jingsai 竟賽), the second character is written in a simplified form that suggested the wrong pronunciation (xi). The white mug with stenciled blue writing was a reward to workers employed by the China Department Store for a successful first quarter of 1953. [See ⧉source: 1953 China Department Store enamel mug]

The Décor of the 1956 Washbasin

The design chosen for the washbasin [see ⧉source: 1956 Washbasin, interior, exterior, factory seal] was likely to please women, who would have been the majority of the cohort that was being celebrated: the dependents of military martyrs and honorably discharged veterans. In the center of the basin is a picture of a young woman in pigtails. Seated in a rattan chair, she is wearing a yellow blouse with red flowers and a green jumper. The bright colors resonate with the aesthetics of the French Fauvist movement. Pausing over a sketch of an airplane on her desk, she gazes out the window at an air plane soaring overhead.

The picture, like the inscription, was created by spraying colored frit over stencils. For each color, a stencil was cut into the desired shape. A minimum of ten stencils would have been needed for the elements in yellow, orange, red, two tones of green, blue, grey, pink, rust red, and black. Each stencil had to be cut exactly right, an easy task for those practiced in the arts of paper cutting and woodblock printing. Guided by registration marks, the stencils had to adhere tightly to the surface to avoid the color spreading, which would have been a challenge given the indentation of the foot and curvature of the basin. In some places the registration was not perfect; the rust-red line that defines the back of the left hand overlaps the pink skin color.

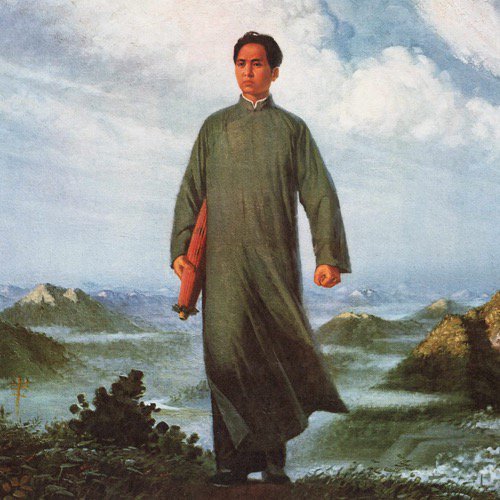

Is the young woman in the design thinking of becoming an engineer? Possibly. But she may also be hoping to be an airplane pilot. During the Republican era, several women were renowned for their aeronautic skills, particularly the intrepid Wang Canzhi 王燦之 (1904-1967), the daughter of the Qing feminist and revolutionary martyr Qiu Jin 秋瑾 (1875-1907). In 1928 after university studies in Hunan province, Wang Canzhi enrolled in New York University where she studied aircraft design and aeronautics. In 1930 she returned to China to become China’s first woman pilot [see ⧉source: Descendant of Qiu Jin visits East China Normal University].7 Other women followed her lead. In the 1950’s photographs and posters of women pilots and parachutists were a way of illustrating the liberation of women and Mao Zedong’s dictum 'Women hold up half the sky.' [See ⧉source: Women pilots and parachutists]

Factory Seal and the Confiscation of Private Businesses

The round factory seal on the bottom of the washbasin features a traditional motif of three peaches with centuries-old associations of longevity [see ⧉source: 1956 Washbasin, interior, exterior, factory seal Image 3 factory seal]. Inside the bottom rim of the circular seal, five characters read 'Product of Enamel Factory' (tangci chang chupin 搪瓷廠出品). The numeral 9 probably refers to the product line. The seven characters on a curving band read, 'Tianjin Public-Private Cooperative' (Tianjinshi gongsi heying 天津市公私合營). In the 1950s, Public-Private Cooperatives were a step in reorganizing economic life on a Soviet socialist model. The PRC’s First Five Year Plan (1953-1957) required the gradual nationalization of all private property. Privately-owned businesses were required to partner with the government. The shift from public-private to fully state-owned enterprises or SOEs (guoying 国营) quickly followed.

Conclusion

With the advent of indoor plumbing and cheaper plastic washbasins for those who still wanted them, enamel washbasin production was discontinued sometime in the 1990s. However, the 1956 washbasin remains an instructive object for a year of social and economic transition. It is representative of an object of daily use that was ubiquitous throughout China in the Mao era. It exemplifies the high quality of craftsmanship in the manufacture of vitreous enamelware. The decoration idealizes the liberation of women in Mao’s China by referencing women pilots and indirectly celebrating the women who were then serving in the air force. While acknowledging contributions to establishing socialism, the inscription documents the written language reform that introduced simplified characters in 1956. Finally, the factory seal refers to the nationalization of private businesses following the Soviet model.

Footnotes

Enameled surfaces are all around us: the inside of ovens, the outside of many kitchen appliances, bathroom fixtures, water fountains, and classroom white boards to name a few.

For a video showing the complicated process, see Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4bMq9gcc98).

After McGregor built his first factory, he cofounded an enamel factory with Xu Daosheng in the late 1910s. See York Lo 'Industrial History of Hong Kong'. (https://industrialhistoryhk.org/hsu-long-sing; accessed 14 December 2018).

Xu Yan, 'Korean War: In the view of Cost-effectiveness', Consulate of the PRC, New York (http://newyork.chineseconsulate.org/eng/xw/t31430.htm; accessed 14 December 2018). Western sources put the figure considerably higher.

'A Plan to Simplify the Chinese Written Language', People’s China, 1 May 1955, 36.

Wei Chueh, 'Reform of the Chinese Written Language', People’s China, 1 May 1955, 33-35. This idea proved impractical because Chinese characters are not phonetic units but carriers of meaning.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Washbasin: Good Hygiene

- ⧉Image Washbasins In Factory Nursery

- ⧉Image Washbasin: 1956 Interior, Exterior, Factory Seal

- ⧉Image Washbasin: Hydrogen Bomb Design

- ⧉Image Washbasin: Lanzhou 'Prize'

- ⧉Image Washbasin: 1953 China Department Store Enamel Mug

- 文Text Washbasin: Descendant Of Qiu Jin Visits East China Normal University

- ⧉Image Washbasin: Women Pilots And Parachutists

Geography

Timeline

Further Reading

Anon. 'A Plan to Simplify the Chinese Written Language'. People’s China, 1 May 1955.

Henriot, Christian. 'The Great Spoliation: The Socialist Transformation of Industry in 1950s China'. European Journal of East Asian Studies vol. 13, no. 2 (2014): 155-162.

Wei Chueh, 'Reform of the Chinese Written Language' (Answering Your Questions), People’s China, 1 May 1955.