Christine I. Ho, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Summary

Many propaganda images were produced by cultural workers to be experienced on public walls, either as murals or blackboard paintings. In villages and communes, mural and wall images were key visual forms for conveying ideology, popular knowledge, and political campaigns, but peasants also participated in making propaganda as mass art. During the Great Leap Forward, peasants were mobilized through the mass mural campaign in order to demonstrate the creative revolution in the countryside. In order to understand how these images became so pervasive in message and style, this entry describes the production, themes, and major concepts behind wall art.Introduction

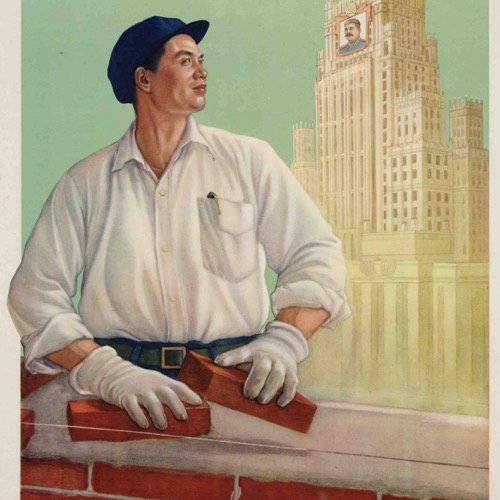

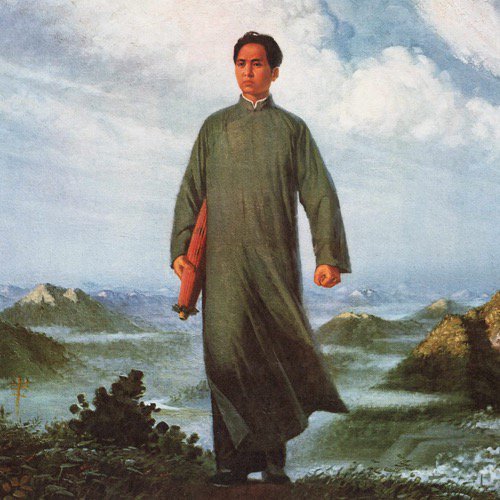

The visual and material environments of socialist China were awash in murals [see ⧉source: Great Leap Forward, handscroll painting by Guan Shanyue, also depicted to the left]. Over life-sized in scale, brightly colored, rendered in clear designs based upon simplified outlines, and explained with short slogans, murals (bihua 壁画) and wall paintings (heibanhua 黑板画 or qianghua 墙画) were drawn by cultural workers on public buildings and blackboards in both cities and villages to reach residents, disseminating political propaganda, news and current affairs, statistics on economic production, and even popular lessons on science and art. Painting on public surfaces was more than an act of individual expression. Instead, the very size and physicality of the mural created a collective experience that was viewed as a key channel for addressing the public and enveloping the material life of a community. Urban dwellers and rural citizens not only experienced murals on the street in their daily lives, but also participated as amateur artists in creating wall paintings as a form of mass art. Beginning with the Great Leap Forward in 1958, cultural cadres organized mural-painting campaigns, mobilizing art groups in work units, peasants, and factory workers to paint murals themselves as a form of folk art, creating what were called 'outdoors art galleries.' Although most have disappeared, how-to manuals, pictorials, and exhibition catalogues that promoted wall painting demonstrate how murals were employed to shape the everyday lived experience of Maoist China.

Making wall paintings

Wall paintings were a major responsibility of cultural workers as they carried out the 'mass art' campaigns (qunzhong meishu 群众美术) of socialist China. At the first meeting of the Literary and Arts Workers’ Conference in July 1949, administrators committed to the expansion of mass art campaigns by institutionalizing a Soviet-influenced format of the 'worker’s club,' designed as after-dinner centers of leisure where workers could read state magazines and periodicals; participate in cultural activities, such as theater, painting, and photography; and to see the fruits of their creative labor in the form of exhibitions and performances. Under the Propaganda Department, each province’s propaganda bureau subsequently opened a Mass Art or Culture Gallery (qunzhong yishuguan 群众艺术馆), which managed the relationship with the county-level cultural stations (wenhua zhan 文化站), frequently by converting ancestral temples or other former religious complexes into secularized cultural spaces. The most visible of these was the conversion of the Imperial Ancestral Temple in Beijing into the Worker’s Culture Palace (wenhuagong 文化宫), completed by International Worker’s Day in 1950. By 1953, according to the statistics provided in the first Five Year Plan, the number of Cultural Galleries nationwide had reached 2,455, and 4,296 Cultural Stations had been established.

Art-training manuals for the mass art galleries and stations anticipated that cultural workers at all levels would be engaged in wall painting. One of the earliest published handbooks on producing mass art was compiled in 1950 by students and faculty at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, who organized their lessons from teaching art classes to factory workers in north China as a Handbook for a Short-Term Art Training Class [see ⧉source: 1950 Mass art handbook]. Adapted from a Soviet manual, the handbook provides a crash course divided into the basic foundations of the visual arts (copying, sketching, basic human anatomy, basic perspective, composition, color, illustration, narrative cartoons (lianhuanhua 连画画), and posters), and functional art, including blackboard design, art typography (meishuzi 美术字), enlargement of portraits of political leaders, and the design of meeting rooms [see ⧉source: 1950 Mass art handbook]. Following the departure of art professors and students, the handbook was meant to help villagers and workers to continue decorating the public blackboard on a daily or weekly basis, while low literacy rates meant that news, information, and education had to be conveyed by pictorial means, created by someone who understood how to reconfigure the decorative patterns, heading designs, and line drawings of Party leaders into a coherent whole.

Art supplies presented a major challenge for cultural workers. Even if wall painting did not depend upon sophisticated technologies of mass propaganda, such as radio and film, there was nonetheless a limited supply of art materials to rural areas. In another handbook on wall painting produced by the Mass Art Gallery in Yunnan province, the art workers recommend a range of substitutions for expensive art supplies, suggesting that palm fronds could take the place of oil painting brushes; pots for boiling ox-glue and stoneware dishes for eating could be used for holding water and pigments; and industrial and agricultural lime and leftover soot pressed into service as pigments, bound with ox-glue, instead of premixed oil paints. In order to paint murals, the village artist would also need a ruler, ruled-line chalk bag, and two ladders. Here the art workers explain that the chalk bag could be a do-it-yourself affair, a round bag fashioned out of cloth, measuring 1 ½ inches by 3 or 4 inches, filled with chalk, and threaded with a cotton string, so a temporary grid could be scored on the side of a building to enlarge a preexisting design [see ⧉source: Mural toolkit].

Topics, themes, and images

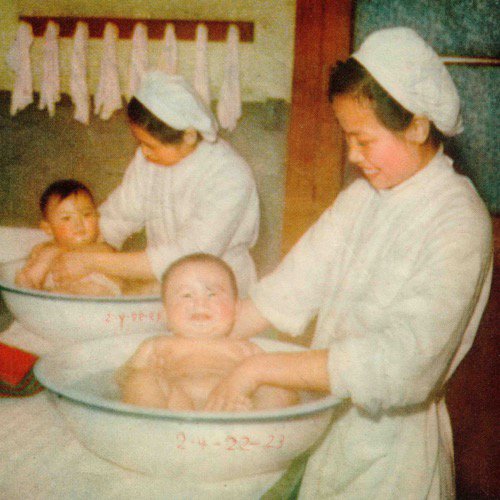

Stock images published in mass art how-to manuals supplied the cultural workers with a repertory of themes and subjects for wall paintings and murals. Mass art how-tow manuals typically included suggested stylized characters, graphic headings to divide the text (baotou 报头) and decorative scrolls and borders to embellish the public noticeboard [see ⧉source: 1958 Mass art handbook]. Beyond promoting grand socialist ideology through slogans, murals reinforced political campaigns by exhorting a commune or work unit to invent new farming technologies, to eradicate the 'Four Pests,' to increase literacy, to mandate attendance at elementary school for girls and boys, or to participate in sports. These images were designed by professional artists or extracted from Soviet examples, then simplified into clear, legible line drawings that were re-published in these small handbooks. For example, one suggested design as the basis for a wall paining in the village is an image by the famous cartoonist Zhang Guangyu 张光宇 celebrates the installation of loudspeakers in the village, accompanied by an easy-to-read verse [see ⧉source: Zhang Guangyu mural design]. Zhang Guangyu’s sweet, charming design is an unusual one, an inventive black-and-white drawing (heibai hua 黑白画) that transforms a trellis of morning glories into loudspeakers, a common trope of likening everyday objects to socialist innovations. The result of the mass art handbook for making wall paintings was consistent dissemination of style and subject, which would become further standardized during the Cultural Revolution, as a stock repertory of political caricatures and united worker-peasant-soldiers accompanied displays of 'large-character posters' (大字报) [see ⧉source: Cultural Revolution mural wall painting].

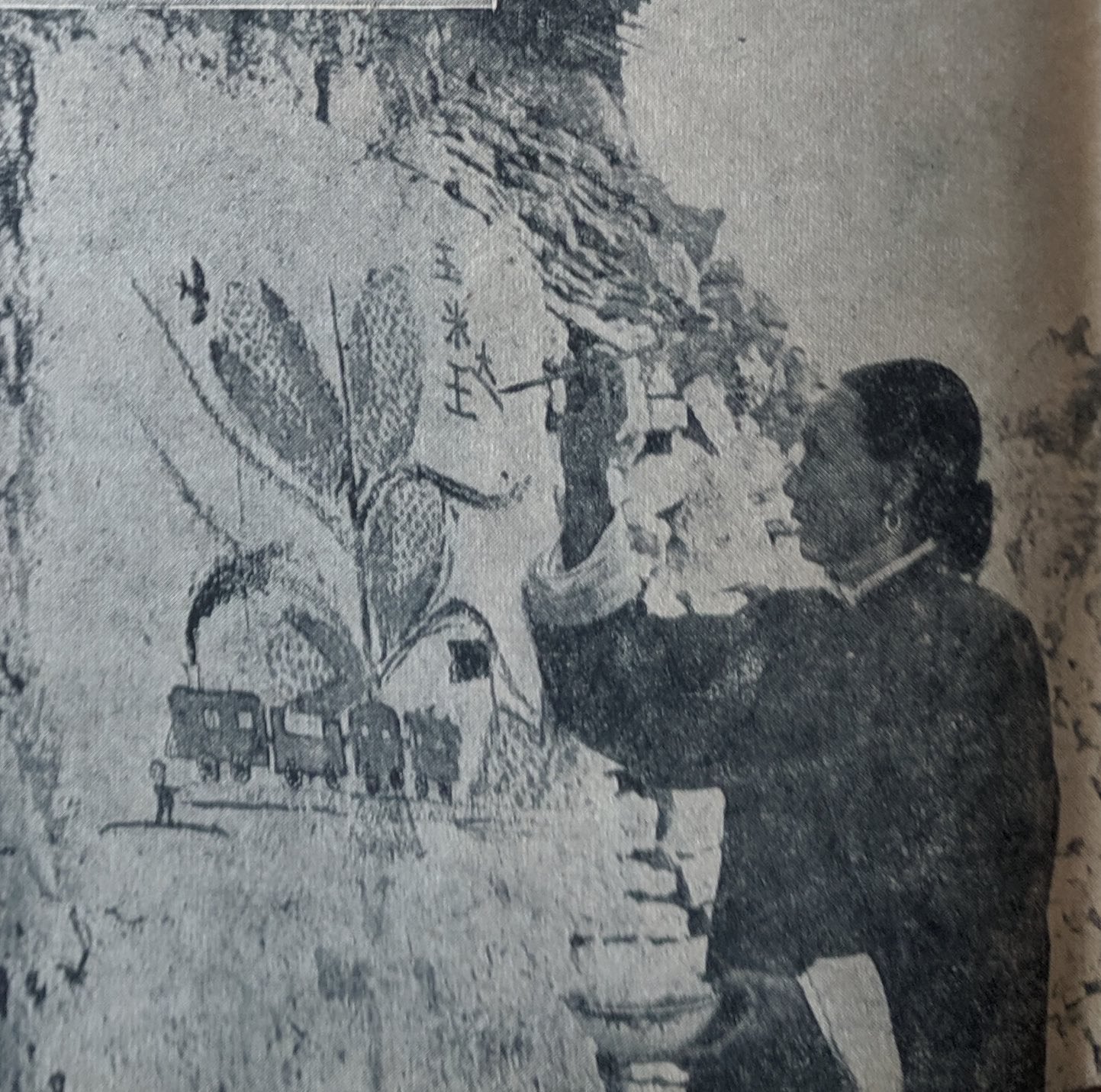

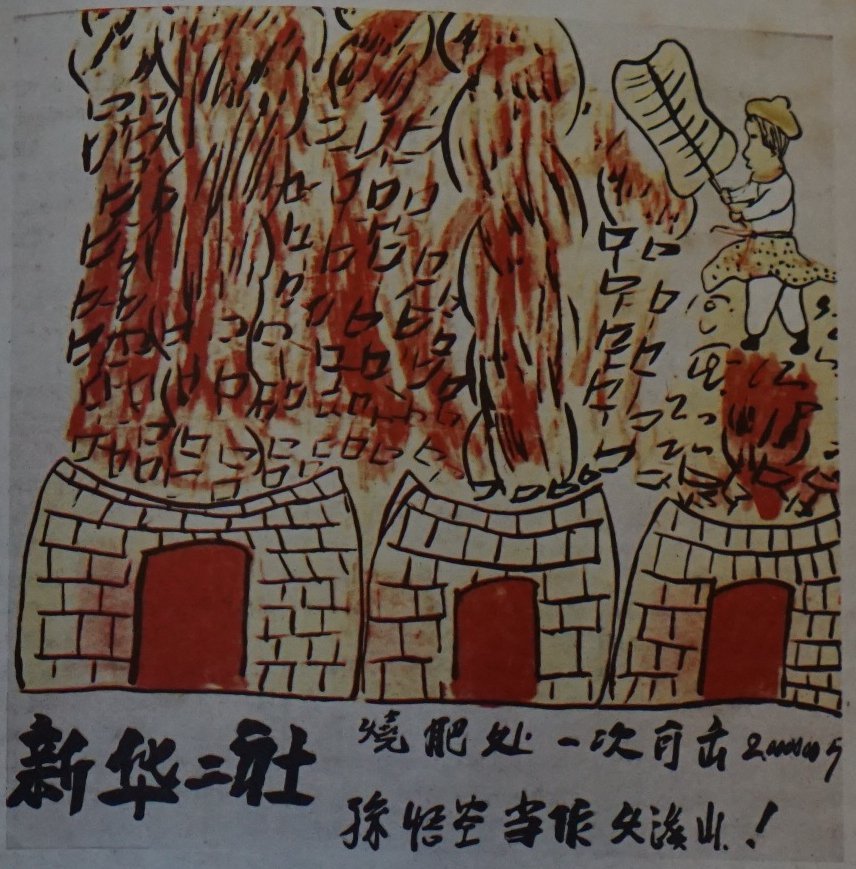

During the Great Leap Forward, mural painting reached a zenith. Deviating from the professional models and Soviet-style designs that had dominated wall paintings and murals, the mural painting campaign celebrated peasant creativity by referencing folk beliefs in a crude, quasi-primitive style, and supposedly inspired by similar folk practices of drawing apotropaic images on walls. As a result, the process and imagery that had accompanied the production of blackboard and wall paintings were exaggerated and expanded in scale, expanding across all available walls of the village. Originating in Guanhu Town 观湖镇, Pi county 邳县, Jiangsu province, the mural campaign sponsored by cultural cadres resulted in a reported 100,000 murals painted by villagers, including peasants, during the summer months of 1958. The result was what cultural administrators, who visited Pi county from Beijing, called an 'outdoor art gallery,' the surfaces awash with murals, as well as posters, cartoons, and papercuts produced by amateur artists. The murals drummed up popular enthusiasm for agricultural collectivization and small-scale industrial production. Among these murals was a work titled 'Corn King' painted by a peasant woman known as Aunt Liang (liang dajie 梁大姐), which exaggerates the size of the harvest metaphorically through oversize cobs towering over trucks [see ⧉source: Auntie Liang mural, also depicted to the right].

The most celebrated mural of the Pi county mural campaign was one produced a peasant identified as Wang Fuwen 王福文 [see ⧉source: Wang Fuwen, also depicted to the left]. Painted in primary colors and an unskilled hand, the mural depicts three fertilizer furnaces, fanned by the mythological figure of Sun Wukong 孙悟空, a cheeky, mischievous monkey with supernatural powers who was immortalized in the Ming dynasty popular novel, Journey to the West. On the mural, the Monkey King’s diminutive stature magnifies the expanse of the conflagration as flames stretch over his head; below is a poem written by an amateur poet Ding Shan 定山, which reads, 'The manure-burning place can attack 2 million catties at once, like Sun Wukong overtaking the volcanic mountains!' Critics of the period acclaimed the work for displaying the naïveté and ingenuity of the peasant creator.

Well into the 1980s, Pi county was still known as the 'mural county' in the People’s Daily [see ⧉source: Report on Pi county murals, from People’s Daily]. The Pi county mural campaign spread to nearby Nanjing, where amateur artists in work units (danwei 单位) such as textile factories turned out in full force to create murals on the street.

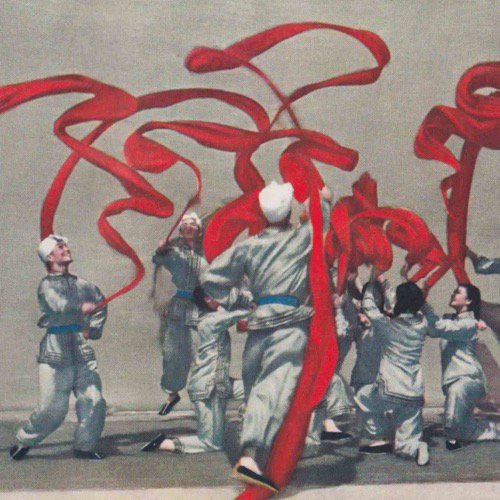

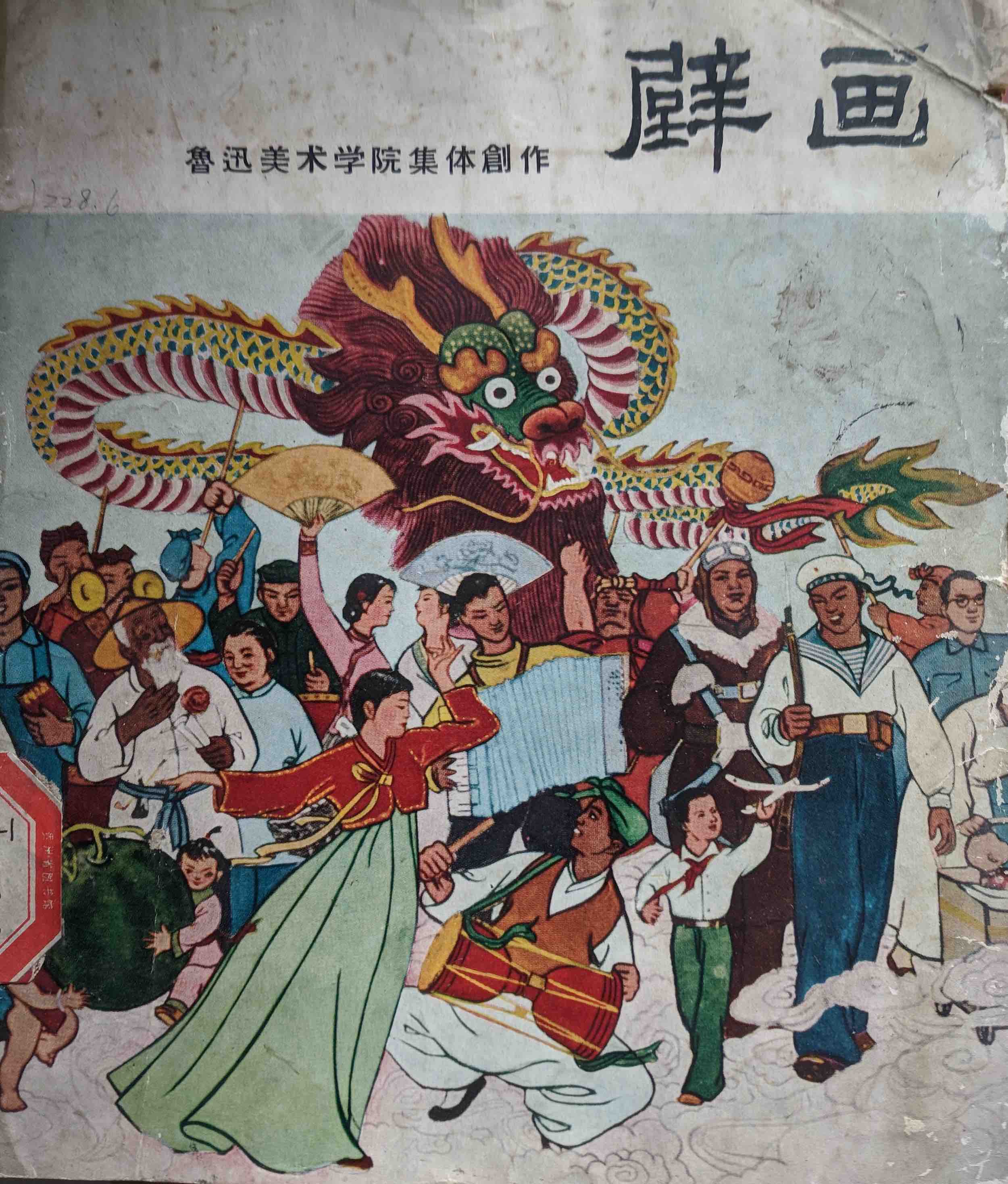

Throughout the cities, teachers and students at the state art academies also took up mural painting in public spaces and walls. When professional artists painted these murals, they deliberately mimicked the thick outlines, auspicious symbols, and rural subjects derived from the amateur murals, such as the image of the chubby-cheeked baby holding a carp, both symbols of abundance [see ⧉source: Professional artists painting peasant murals]. In the case of a mural collectively created by the painting department at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Art, chosen as the cover the artists have chosen bright flat colors and a heavily linear style to convey a festive procession for the Dragon Boat Festival, where all of the citizens of the new socialist state – including ethnic minorities – are celebrating with dances, music, and an overgrown melon [see ⧉source: Murals by Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, also depicted to the right].

Murals and wall paintings were distinctive features of the lived environment of Maoist China, responsible for perpetuating some of the most striking imagery of the period. Easily whitewashed over and repainted, the continual production, flimsy materiality, and standardized iconography of murals and wall paintings were designed to be so embedded within the everyday world that they ceased to become an object of interest.

Popularization Art Gallery, Beijing Zoo

One extant example of socialist wall painting is preserved as the 'popularization art gallery' (puji hualang 普及画廊) at the Beijing Zoo [see ⧉source: Beijing Zoo, also depicted to the left]. Constructed in 1958, the popularization art gallery is built out of industrial materials: poured concrete for the base, pillars, and overhanging eaves; stacked bricks for support; and decorated with ornamental iron lattice and frame. A freestanding wall is divided into ten bays, each measuring approximately 3 feet in length; the wooden boards that span each bay result in twenty horizontal placards. Made out of simple, easily accessible materials, the gallery is designed as a permanent, durable, outdoors exhibition space, and planned as a flexible format that allows cultural workers to repaint the placards according to necessity.

The plaque commemorating the popularization gallery’s legacy specifies two formats of public presentation: hand-painted designs and three-dimensional display windows. The three-dimensional display windows also reinvent inexpensive materials in order to configure an active viewing experience, entertaining as well as educating: painted vertical strips are set in regular intervals within a wood hexagonal frame, akin to a louvered window. Rather than a single perspective, different images appear as the viewer changes viewing position: from the front, the visitor reads the yellow-and-red characters for 'the world of animals'; from the left, the visitor beholds a painting of swans paddling in water; and from the right, an image of an tiger [see ⧉source: Popularization gallery]. While the placards have been updated with recent campaigns such as announcing the importance of vaccinations against the bird flu, their current content and form deliberately refer to the dissemination of scientific knowledge to popular audiences through easily digestible forms, a key feature of Maoist scientific practice. As a palette of primary colors and anthropomorphized cartoon animals illustrate the songs of the humpback whale with musical notation, the mural as science dissemination makes wildlife biology catchy, intelligible, and clear to young and old visitors alike [see ⧉source: Whale].

The designers of the zoo’s popularization gallery conceived of zoological knowledge imparted through approachable means, disseminated in a format that could be seen by a large group, and calculated its pictorial engagement for its intended audience, children. Both the simplicity and accessibility of selected materials and techniques employed in the zoo’s popularization gallery reinforce the goal of popular edification. The material presentation of wall painting, in other words, manifests the belief that culture and knowledge no longer belonged to the elite, but to a mass audience.

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Murals: Great Leap Forward, Handscroll Painting By Guan Shanyue

- ⧉Image Murals: 1950 Mass Art Handbook

- ⧉Image Mural Toolkit

- ⧉Image Murals: 1958 Mass Art Handbook

- ⧉Image Murals: Zhang Guangyu Mural Design

- ⧉Image Murals: Cultural Revolution Wall Painting

- ⧉Image Murals: Auntie Liang

- ⧉Image Murals: Wang Fuwen

- 文Text Murals: Reports On Pi County Murals, From People's Daily

- ⧉Image Murals: Professional Artists Painting Peasant Murals

- ⧉Image Murals: Murals By Lu Xun Academy Of Fine Arts

- ⧉Image Murals: Beijing Zoo

- ⧉Image Murals: Popularization Gallery

- ⧉Image Murals: Singing Whale

Geography

Timeline

Further Reading

Andrews, Julia F. Painters and politics in the People’s Republic of China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. Especially pages 225-227.

Croizier, Ralph. 'Hu Xian peasant painting: From revolutionary icon to market commodity,' in Richard King, ed., Art in Turmoil: the Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966-76. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010. Especially pages 136-165.

Johnston Laing, Ellen. 'Chinese Peasant Painting, 1958-1976: Amateur and Professional'. Art International vol. 17, no. 1 (1984): 2–12, 40, 64.

Johnston Laing, Ellen. The Winking Owl: Art in the People’s Republic of China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. Especially pages 31-32.